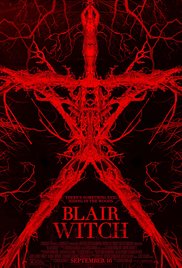

Oh! The Horror… | Of Blair Witch (2016)

“A third and final transformation to the magic circle has to do with the disappearance of the circle itself, while its powers still remain in effect. During [Lovecraft’s story, “From Beyond”], as the characters witness the “beyond,” the device itself gradually recedes into the background as the characters can only look about in a state of horrified awe….natural and supernatural blend into a kind of ambient, atmospheric no-place, with the characters bathed in the alien ether of unknowable dimensions. The center of the circle is, then, really everywhere…and its circumference, really nowhere.” -Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet, pg. 77

As mentioned in the last column on the first two Blair Witch installments, it is very difficult to separate the series of films within the mythology from the highly creative and successful marketing campaign that was able to blur the lines between truth and fiction. It is difficult to read these films apart from that initial extra-textual element and the new film—directed by Adam Wingard and written by Simon Barrett, who also brought us You’re Next and The Guest—is no different. For the average moviegoer, their opinion of the first film will probably be a solid gauge for how the new installment is experienced and received. However, this was not my experience with the film on the first viewing.

As mentioned in the last column on the first two Blair Witch installments, it is very difficult to separate the series of films within the mythology from the highly creative and successful marketing campaign that was able to blur the lines between truth and fiction. It is difficult to read these films apart from that initial extra-textual element and the new film—directed by Adam Wingard and written by Simon Barrett, who also brought us You’re Next and The Guest—is no different. For the average moviegoer, their opinion of the first film will probably be a solid gauge for how the new installment is experienced and received. However, this was not my experience with the film on the first viewing.

I had gone into the movie with two notes of speculation about the film: 1) it would probably be my favorite entry into the film series and 2) it would lack the conceptual audacity of the first two. My expectations were high once the film—formerly known as The Woods—was revealed to be a Blair Witch film. Those heightened circumstances are often a catch-22, however. If the movie turns out to meet and/or surpass expectations, it can be the most glorious film going experience, but if it fails to meet expectations…well, it can be disheartening to put it mildly. This is why it was a strange sensation for me to come out of Blair Witch not knowing whether it met those expectations or not.

Every time I thought about something in the film that I really appreciated, I found a problematic element that accompanied it. For instance, I really appreciated the fact that Wingard and Barrett actually give the audience a glimpse of something in the woods instead of relying solely on rustling twigs and distant cackles and never actually making good on the promise. Those tactics may have worked within the overall promotional experience of the first film at the time, but on repeat viewings—divorced from 1999—it felt like a bit of a tease.

However, on the other side, the film attempts to elevate the mythology by leaning into the time loop/travel elements that the first film alluded to and the second film attempted, poorly, to utilize. While this theme is a perennial favorite topic of philosophy students and sci-fi fans alike, it is extremely hard to find a way to make a satisfying narrative strand out of it, especially when that is not the central focus of the film. In the days following my first viewing, that element began to feel more and more tacked on to the film. Like I said before, I was at a stalemate with the film.

So I did what I always do with films that leave me in an uncomfortable ambivalence: I went and saw it again. I must say that my opinion of the film did shift a little. I still appreciated the presence of the being presented in the woods, but I actually grew to mildly appreciate the time travel/loop strand of the narrative. It felt less tacked on than it did before.

However, the element that captured my attention this time around was an idea that I began to revisit in my head, something I had read about in Eugene Thacker’s terrific book, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy Vol. 1. In the book, Thacker sets out to show the limitations of human reasoning (philosophy) and human exploration of the natural world (science), while attempting to create a post-human perspective on the planet, a perspective where humanity is displaced from centrality—a planet not “sensed”. He does this by exploring various texts, non-fiction and fiction.

However, the element that captured my attention this time around was an idea that I began to revisit in my head, something I had read about in Eugene Thacker’s terrific book, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy Vol. 1. In the book, Thacker sets out to show the limitations of human reasoning (philosophy) and human exploration of the natural world (science), while attempting to create a post-human perspective on the planet, a perspective where humanity is displaced from centrality—a planet not “sensed”. He does this by exploring various texts, non-fiction and fiction.

However, the above quote comes from his discussion of Lovecraft and the concept of the “magic circle.” The magic circle is a concept that appears in various forms within fiction where there is a circle that contains people within it who are able to safely conjure and view the supernatural from the safety of the circle’s center. Thacker, however, shows that H. P. Lovecraft ends up destroying the concept of the circle by flattening it out to the point where there is no longer a separation between “natural” and “supernatural” and, therefore, there is no safety from what might be revealed from the “hiddenness of the world.”

The setting of Blair Witch, the Black Hills Forest, then morphs from an example of a flattened magic circle to a nonexistent circle mediated by a device, however the movement in this film is the reverse of most occult stories. The feeling we get as viewers is that these woods are on the outside of the circle and once our protagonists move beyond the fence line out of the magic circle’s center, they become opened up to that which has been conjured before them. The device spoken about in Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” finds its analogue in the use of all of the video cameras, something that is becoming a classic mediation tool between natural and supernatural. As the movie goes on, we see that the separation between the center (the safety) of the circle begins to recede like it does in “From Beyond” and the device effectively becomes the separation point.

We find out in the final scenes of the film, something has drawn all of these characters to the woods. Something from the outside of the “circle” had transgressed that safe line and drawn them out of the center of the circle, the safety of a materialist reality. Once out of the center, they are left only with their cameras as the final separation they have from that which the witch or whatever is haunting the woods has conjured up. However, safety no longer exists—there is no center anymore—and we see exactly what Thacker speaks about with the blending of natural and supernatural, the ambient atmospherics and the bathing in the alien ether of unknowable dimensions. Knowledge attained within this new, frightening world leads to death. They see the witch and they die from the fright of hiddenness revealed before their eyes.

We find out in the final scenes of the film, something has drawn all of these characters to the woods. Something from the outside of the “circle” had transgressed that safe line and drawn them out of the center of the circle, the safety of a materialist reality. Once out of the center, they are left only with their cameras as the final separation they have from that which the witch or whatever is haunting the woods has conjured up. However, safety no longer exists—there is no center anymore—and we see exactly what Thacker speaks about with the blending of natural and supernatural, the ambient atmospherics and the bathing in the alien ether of unknowable dimensions. Knowledge attained within this new, frightening world leads to death. They see the witch and they die from the fright of hiddenness revealed before their eyes.

While I do not know the intent of Wingard and Barrett in creating this new story within this mythology and I do not know their level of familiarity with past occult narratives, I do think they are following in a familiar path as Lovecraft except they do it with witches instead of creatures with tentacles and with modern cameras and technology instead of “the device.” What seems true and fitting about them both, however, is that they see a reality that contains within its borders a seamless blend of the natural and the supernatural, which Christianity has traditionally held as well. What they bring forth from that truth is something that I often sense is forgotten in modern American Christianity: there is no safety in this reality. No matter how humanity reasons or explores the natural world, there will always be something beyond the veil that defies comprehension and presents a challenge to our society’s obsession with safety.