Around the middle of the decade, Harper’s critic Charles E. Whittaker gave a scathing film review. Art is supposed to be expressive, he said; but the idea of “art” is far from the movie…

…not merely in absence, but in positive antithesis—because the chief effort of the movie seems to be to present something that shall express life, not as the manufacturer sees it, but as he imagines somebody else wants to see it. This is not art but artifice.

It’s the hottest of hot takes: Hollywood abandoning artistry for crowd-pleasing, market-powered schlock that they think the crowd wants to see. Film as manufacturing, not art. Whittaker surely got a lot of retweets of that gem.

Or he would have, if Twitter had existed in 1916. He wrote those words a century ago; and Whittaker wasn’t talking about a particular film, either, but about film as a medium. He was convinced that he would outlive movies, and that in the future, people would only remember them because of documentaries about “the reproductions of life in the trenches and in the whaling boats,” further insisting that “The movie is not art, because it is not literature; it has no persistence, save for its illustration of daily news. The life of the best of the photodramas, on the word of Mr. Daniel Frohman, is two years.”

Or he would have, if Twitter had existed in 1916. He wrote those words a century ago; and Whittaker wasn’t talking about a particular film, either, but about film as a medium. He was convinced that he would outlive movies, and that in the future, people would only remember them because of documentaries about “the reproductions of life in the trenches and in the whaling boats,” further insisting that “The movie is not art, because it is not literature; it has no persistence, save for its illustration of daily news. The life of the best of the photodramas, on the word of Mr. Daniel Frohman, is two years.”

But “photodramas” were still around a decade later for British critic Walter Mycroft to gatekeep similarly, when he lambasted American films for their frivolity, vulgarity, and “false outlook on life.” And yet a decade after that, they still remained for Raymond Spottiswoode to bemoan that stupid people were watching them: “Lower and lower levels of intelligence [have been] drawn into the cinemas; the same films [are] supposed to satisfy every type of audience; and hence the general taste becomes increasingly depraved.”

Ironically, Mr. Whittaker, Mr. Mycroft, and Mr. Spottiswoode would find a great deal of kinship with film legends Martin Scorsese, Ken Loach, and Francis Ford Coppola.

In interviews over the past few weeks, Scorsese has been asked about Marvel films in general; he characterized them as “theme parks” and labeled them “not cinema,” though he admitted that he didn’t watch them. Loach invoked English poet William Blake and suggested that the money surrounding the MCU made art “impossible,” and that the stories were “a cynical exercise […] a market exercise.” Coppola took the sentiment still further, calling superhero films “despicable.”

Guardians of the Galaxy director James Gunn responded with disappointment, tweeting, “I was outraged when people picketed The Last Temptation of Christ without having seen the film. I’m saddened that he’s now judging my films in the same way.” Disney head Bob Iger said the films speak for themselves, telling a Wall Street Journal interviewer, “Are you telling me that Ryan Coogler making Black Panther is doing something that somehow or another is less than anything Marty Scorsese or Francis Ford Coppola have ever done on any one of their movies? Come on.” And Thor: Ragnarok director Taika Waititi took the whole discussion down to the basics, telling AP Entertainment, “Of course it’s cinema! It’s at the movies. It’s in cinemas…,” though he couldn’t resist ending his sentence with a joke, “…near you.”

Great as Scorsese and Coppola are, they are fundamentally wrong about the artistic value of superhero films. Far from a flash-in-the-pan fad or market exercise, far from a theme park for the masses, I believe that we’ve witnessed the birth of a full-fledged new genre over the past two decades; and like the Western and Sci-fi genres before it, the Superhero genre is defining itself with its own identity, tropes, and narrative structure.

Superheroes are a Genre

Every genre has to have its own identity. Western films are defined by their setting, of course, but also by their loner protagonist with his trusty steed and a particular frontier justice meted out by high-minded individuals. Romantic comedies have a particular structure, with a meet-cute, a tragic misunderstanding, and a final reunification. Heist films have a particular language to them; when a plan is going perfectly, it communicates that the inevitable hiccup in the plan is going to become an even greater crisis.

And a superhero film has its own identity, too: a unique person or individual in our world (or one like it) becomes even more singular with the addition of some kind of superpower. Their support structure and broadly-drawn villain are introduced. In the end, the protagonist faces a sort of mirror of themselves, often with similar powers deployed for evil instead of for good, who challenges the hero not only physically but emotionally. Its tone is usually hopeful in some way, and while it doesn’t take itself too seriously, it’s not a comedy or a farce.

This identity doesn’t fit neatly in the action, sci-fi, fantasy, thriller, or comedy genres. It sits as its own genre; one just as valid as drama, mystery, or romance. Though it is a fairly new one, arising rapidly over the last two decades (while the classic Christopher Reeve Superman films of the 1970s gave an early preview of the genre, the 1980s and 1990s gave us Batman films which eschewed much of the identity of a superhero film in favor of quirky action-comedy, as 2000’s X-Men did in favor of sci-fi action).

This identity doesn’t fit neatly in the action, sci-fi, fantasy, thriller, or comedy genres. It sits as its own genre; one just as valid as drama, mystery, or romance. Though it is a fairly new one, arising rapidly over the last two decades (while the classic Christopher Reeve Superman films of the 1970s gave an early preview of the genre, the 1980s and 1990s gave us Batman films which eschewed much of the identity of a superhero film in favor of quirky action-comedy, as 2000’s X-Men did in favor of sci-fi action).

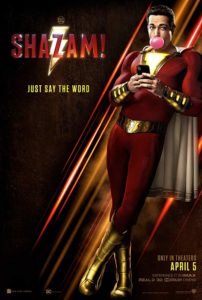

The first modern example of a film in the superhero genre is Sam Raimi’s 2002 blockbuster Spider-Man. This film, broadly speaking, established the identity that would become the superhero genre; the pattern was parodied by My Super Ex-Girlfriend in 2006 and subverted by Megamind in 2010. DC tried the formula out in 2013 with Man of Steel, though it didn’t really take root with that studio until 2019’s Shazam!.

But the most crystallizing and globally-recognized example of the genre was, undoubtedly, the first chapter of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Starting with 2008’s Iron Man, the phenomenon kicked into high gear with The Avengers in 2012, and was capped off with 2018 and 2019’s one-two punch of Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame.

The two-decade history of the genre has dipped its toes into cross-genre storytelling, too, particularly in more recent years; 2014’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier was a superhero film and a political thriller, and the same year gave us a superhero film blended with a space opera in Guardians of the Galaxy. 2018’s Black Panther gave us a regal moral quandary among its superheroics; later that year, Aquaman put a superhero film inside a fantasy epic; and in the same month we got a high-octane animated superhero coming-of-age tale with Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Of course, superhero films aren’t good just because film turned out to be an art form in defiance of early critics, they’re not culturally valuable just because the Western genre got its own section in the Blockbuster Netflix catalog, and they aren’t resonant just because they feature cross-genre storytelling. No, for the films to be worthwhile, they have to be doing something more than just punching and kicking. With these cross-genre films especially, the superhero genre proves that it can uniquely capture or speak to the experience of a particular community; and I think that this is how they became popular in the first place.

Of course, superhero films aren’t good just because film turned out to be an art form in defiance of early critics, they’re not culturally valuable just because the Western genre got its own section in the Blockbuster Netflix catalog, and they aren’t resonant just because they feature cross-genre storytelling. No, for the films to be worthwhile, they have to be doing something more than just punching and kicking. With these cross-genre films especially, the superhero genre proves that it can uniquely capture or speak to the experience of a particular community; and I think that this is how they became popular in the first place.

Superheroes are for a Community

Scorsese, Loach, and Coppola surely know that the Superhero genre is distinct from other genres of form and storytelling. Scorsese himself was originally attached to produce this month’s Joker, even; so he clearly doesn’t think that the genre itself is bankrupt.

It’s Loach, in his invocation of William Blake’ quote that “where any view of money exists, art cannot be carried on,” who reveals the truth of these auteurs’ objections: their problem with superhero films (and with the MCU in particular) is that they’re popular.

This is what drives all the thinkpieces about “superhero fatigue” and the failure of the modern blockbuster. Like Whittaker, Mycroft, and Spottiswoode in the first half of the 20th century, it is the superhero genre’s accessibility and public popularity that bothers these giants of the silver screen. Their comments to the public deriding the most popular shared universe ever invented is the equivalent of the directors stopping their car in front of your house and shouting, “get in loser, we’re having a populism vs. art debate!”

And that’s a fair debate to have; we’ve been having it at least since the 1800s, when Blake wrote his complaint about money and art, but probably for far longer. An ancient Egyptian sculptor was probably called a “sellout” for accepting the commission to carve the Sphinx. There’s a certain expectation that art must be starved to be authentic.

And that’s a fair debate to have; we’ve been having it at least since the 1800s, when Blake wrote his complaint about money and art, but probably for far longer. An ancient Egyptian sculptor was probably called a “sellout” for accepting the commission to carve the Sphinx. There’s a certain expectation that art must be starved to be authentic.

There are other fair criticisms that could be leveled at the Marvel Cinematic Universe in particular: the fact that they’re such massive global financial behemoths means that Disney is loath to cause the slightest harm to the golden goose; since the formula works as it is, the individual style and voice of each director is toned down somewhat in favor of the “Marvel style.” Even as the franchise explores different genre mashups, the resulting product still tends to feel like a Marvel film, not a Russo or Gunn or Wright film.

But these arguments are only ever leveled at art by someone who isn’t part of the community that it was made for.

There’s a reason that the modern superhero film didn’t take root until 2002, and that reason is wrapped up in a number: 9/11. For many of us in the west, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 made us look for heroes in a deeper way. First responders were canonized. Those who made sacrifices in attempts to prevent the attacks were lionized. Churches exploded in attendance. The US Military broke recruitment records. We felt vulnerable for the first time in our adult lives, and we wanted someone to swoop in. When Spider-Man did, we clung to him and refused to let go.

Since then, we haven’t wanted to let go, either. From the 2008 financial crisis to the election of Donald Trump in 2016, there has been a significant percentage of the American population that has felt vulnerable and powerless since that initial hit. Scorsese and Coppola probably haven’t felt particularly powerless recently; they’ve been rich and commanded great respect in the filmmaking world for half a century. But Americans in 2001 felt powerless. Middle-class Americans in 2018 felt powerless. And Millennials in 2019 feel powerless.

The art of a community reflects the hopes and fears of that community; if we’re not part of that community, it’s hard to understand those hopes and fears, and how they’re expressed. Those expressions may even look like nonsense from the outside.

But at the end of the day, every community wants to know a hero. We want to be a hero. And that’s why most superhero films made after 2001 particularly humanize their superhumans.

Superheroes are Human

Bilge Ebiri of Vulture kind of agrees with Scorsese and Coppola in his article about the controversy. “Superhero movies […] haven’t really expanded our capacity for feeling. If anything, they’ve limited it, delivering tales of moral clarity, with ready-made, mix-and-match character interactions.”

I fundamentally disagree, and even think this is a failure in critical examination: the reason that superhero films (and MCU films in particular) are so popular is that they don’t deliver that. In fact, like with any other genre, the ones that succeed are simply good stories, above and beyond their spectacle. Interestingly enough, Ebiri himself immediately refutes his very own assertion with three counter-examples, but doesn’t retract his initial statement.

Good superhero films address our fears and desires, and provide ways for us to work through them. Good superhero films give us hope. Good superhero movies help us wrestle with our convictions and come out stronger on the other side. They expand not only our capacity for feeling but our capacity for empathy and our desire to help. They increase our humanity, even when the hero herself isn’t human. This is the real human experience, and it’s as valid as anything Scorsese and Coppola have ever made (and probably more valid than Jack).

Good superhero films address our fears and desires, and provide ways for us to work through them. Good superhero films give us hope. Good superhero movies help us wrestle with our convictions and come out stronger on the other side. They expand not only our capacity for feeling but our capacity for empathy and our desire to help. They increase our humanity, even when the hero herself isn’t human. This is the real human experience, and it’s as valid as anything Scorsese and Coppola have ever made (and probably more valid than Jack).

In fact, Scorsese and Coppola tap into that very same heart in their own films (well, maybe not in Shutter Island). They aren’t above pressing upon the heart and soul of the narratives they film; and well they shouldn’t be, as that’s the whole point of cinema in the first place.

We’re God-created beings with God-created hearts, so the stories we enjoy will echo His story. In superhero films, we see our God-given desire for heroism and rescue fulfilled. We see people being selfless and reaching out with their own unique gifts. We see our greatest concerns felled with mighty blows. We see a champion arising to defeat our fears.

That’s what a superhero film is, and it’s why we get back on the Marvel-Go-Round every time: we’re seeing our reality being filled up with human hopes. And when we want more, where do we go?

To the cinema.