For a while now I have been contemplating how filmmaking changed with the introduction of sound in film. The dawn of the “talkies” is an innovation that I am not at all sure we have fully come to terms with even to this day. When critics speak of a film’s over-reliance on exposition, they are speaking of a flaw that almost singularly came with the introduction of sound, dialogue, and narration contained within the film itself. Silent cinema—out of technological constraint—had to rely on showing instead of telling. Sure, the action of the film was punctuated with printed text, but much of this was selective dialogue and delineating changes of setting. The dialogue had to be carefully chosen so that the text did not overtake the screen time of the actual cinematic magic of capturing movement. Those old wizards of celluloid had to create meaning without sound. Action drove themes, while cinematography created tone and atmosphere in which the audience could inhabit for an hour, give or take.

For a while now I have been contemplating how filmmaking changed with the introduction of sound in film. The dawn of the “talkies” is an innovation that I am not at all sure we have fully come to terms with even to this day. When critics speak of a film’s over-reliance on exposition, they are speaking of a flaw that almost singularly came with the introduction of sound, dialogue, and narration contained within the film itself. Silent cinema—out of technological constraint—had to rely on showing instead of telling. Sure, the action of the film was punctuated with printed text, but much of this was selective dialogue and delineating changes of setting. The dialogue had to be carefully chosen so that the text did not overtake the screen time of the actual cinematic magic of capturing movement. Those old wizards of celluloid had to create meaning without sound. Action drove themes, while cinematography created tone and atmosphere in which the audience could inhabit for an hour, give or take.

When every word can be captured as they are being said by actors, there is an ease to making dialogue and narration tools to narrow a film’s focus: to prescribe, not to describe. When I view Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc or Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the whole world of these films is opened to the mind’s eye. Every little shadow or character’s look can be translated in numerous ways without language directing audiences towards this or that meaning or theme or concept. Most of all, those old silent films are easier to reside in. When it comes to film, language must serve the flickering image. The history of cinema could probably be succinctly defined by this conflict between sight and sound. Because we are linguistic beasts, we like our beliefs and themes to be clear—to defy misinterpretation—but cinema has always been a descriptive form first and foremost and description often complicates clarity of meaning. Various people can be awash in the universe of Maria Falconetti’s eyes as she is subjected to an arduous trial and come away with multitudes of interpretations. Films that rely on the image create magic. Films that rely on the word, often, create propaganda.

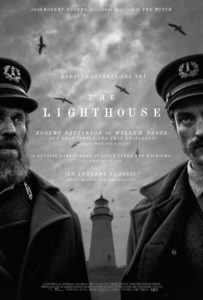

Robert Egger’s 2015 debut, The Witch, was stunning to be sure, however I was one of the few that did not fall into absolute adoration before it. I liked it quite a bit. I thought Egger’s attention to detail, his portrayal of early American religious affections and folklore, and the painterly quality of his cinematography were all very moving. Yet there were other films I enjoyed more that year. Yet I find my mind comes back to specific elements of The Witch time and time again. It has stuck to my bones more than most of the films I placed ahead of it that year. That is feat and one which made me interested in what his next foray into film would entail. Enter 2019’s The Lighthouse.

Robert Egger’s 2015 debut, The Witch, was stunning to be sure, however I was one of the few that did not fall into absolute adoration before it. I liked it quite a bit. I thought Egger’s attention to detail, his portrayal of early American religious affections and folklore, and the painterly quality of his cinematography were all very moving. Yet there were other films I enjoyed more that year. Yet I find my mind comes back to specific elements of The Witch time and time again. It has stuck to my bones more than most of the films I placed ahead of it that year. That is feat and one which made me interested in what his next foray into film would entail. Enter 2019’s The Lighthouse.

Leave it to Egger’s to make his next film a gritty black and white tale about isolated “wickies” maintaining an island lighthouse as storms increasingly rage all around them and their sanities wane. Not only this but filming it in a restrictive 4:3 aspect ratio which calls to mind some of those old silent film ratios. With the exception of this film being a “talkie,” it feels like something from an older time. Yet Eggers is able to utilize the sound and dialogue of the film to obfuscate meaning even more. He and his brother researched the time period and wrote the script with language and terminology that is outdated, if not dead, to a modern audience. On top of this, the accents of Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe) and Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson) are trying for even the most talented translators among audiences. When the words are clear, they are often banal as they speak about the work, frustrations, drink or…farts. Or it is seeming nonsense like the iconic scene where their dialogue consists of alternating “whats.” The only time Eggers lets us into a potential thematic element is when Wake calls down the curse of Poseidon—or some other sea deity—upon Winslow when Winslow declares his distaste for Wake’s cooking. A scene that is suffocating with tension and then released with humor, once again obscuring the potential seriousness of this moment.

Eggers continues with the painting-like cinematography—Jarin Blaschke, who also did The Witch—yet the restricted aspect ratio almost plays against type for sea films. Usually the grandeur of the roiling waves are captured in their full, vivid color and expanses, but seeing them in black and white in what is ultimately a square adds a menacing otherworldliness to the watery landscape. We are constantly wondering what is rising up from the depths beyond the frame. Is it Poseidon, himself, come to rage against humanity? We don’t know, but we know something weird is going on as we are invited into the perspective of Winslow, the grunt of the pair. Along the way, he witnesses the most delightfully designed mermaid, decapitated heads, and a being from the depths with tentacles that may or may not be Wake. Yet, with all the drinking and isolation and mounting tension and revelation about characters, we actually don’t know how much is real and how much could be the revelries of a strained, fragile mind. The final shot as the camera backs away is perhaps one of my favorites of all time. It says so much or so little depending on what parts the viewers chooses to believe are real. I think the ambiguity that Eggers leaves the audience with in this film harkens back to the opening of interpretative worlds that took place in silent film. He was able to disarm dialogue, create a sparse soundtrack, and never give the audience any grounding into what to believe.

Eggers continues with the painting-like cinematography—Jarin Blaschke, who also did The Witch—yet the restricted aspect ratio almost plays against type for sea films. Usually the grandeur of the roiling waves are captured in their full, vivid color and expanses, but seeing them in black and white in what is ultimately a square adds a menacing otherworldliness to the watery landscape. We are constantly wondering what is rising up from the depths beyond the frame. Is it Poseidon, himself, come to rage against humanity? We don’t know, but we know something weird is going on as we are invited into the perspective of Winslow, the grunt of the pair. Along the way, he witnesses the most delightfully designed mermaid, decapitated heads, and a being from the depths with tentacles that may or may not be Wake. Yet, with all the drinking and isolation and mounting tension and revelation about characters, we actually don’t know how much is real and how much could be the revelries of a strained, fragile mind. The final shot as the camera backs away is perhaps one of my favorites of all time. It says so much or so little depending on what parts the viewers chooses to believe are real. I think the ambiguity that Eggers leaves the audience with in this film harkens back to the opening of interpretative worlds that took place in silent film. He was able to disarm dialogue, create a sparse soundtrack, and never give the audience any grounding into what to believe.

And I am a sucker for practical effects. Every fantastical element in the film has a felt weight and dimension to it. The tentacles writhe and flop and the mermaid’s body gradually shifts from milky white breasts and stomach to gills and trout-like tail. As Dafoe and Pattinson interact with each other and Pattinson stumbles across the things that go bump in the night, Eggers treats us to a banquet of imagery and forces the viewer to take in all they saw and piece it together for themselves. Like the great masterworks of the great painters of old and the best of the silent films from the beginning of the last century, Eggers gave us an atmosphere, a space, to inhabit even with all of its tension, otherworldliness and peril. This reviewer found himself entranced in the world like I am when I watch a silent film wondering what is happening beyond the frame. Constriction becomes a space for the freedom of imagination.

And I am a sucker for practical effects. Every fantastical element in the film has a felt weight and dimension to it. The tentacles writhe and flop and the mermaid’s body gradually shifts from milky white breasts and stomach to gills and trout-like tail. As Dafoe and Pattinson interact with each other and Pattinson stumbles across the things that go bump in the night, Eggers treats us to a banquet of imagery and forces the viewer to take in all they saw and piece it together for themselves. Like the great masterworks of the great painters of old and the best of the silent films from the beginning of the last century, Eggers gave us an atmosphere, a space, to inhabit even with all of its tension, otherworldliness and peril. This reviewer found himself entranced in the world like I am when I watch a silent film wondering what is happening beyond the frame. Constriction becomes a space for the freedom of imagination.

1 comment