Towards the beginning of 2016, in their discussion of this year’s indie horror darling, The Witch, within the context of 1973’s cult classic, The Wicker Man, The Next Picture Show podcast (hosted & produced by former writers for, the now defunct, The Dissolve) considered whether it was fair to gauge the success and quality of a horror film by how scary it is. I was glad to hear them bring this question up, because it is something I had been contemplating for several months. Why does it seem like horror’s reception tend to be tied to how well the actual film lives up to its studio’s hype machine with such headlines as “scariest move of the year!” or “the most horrifying experience of the new century!”? To put it more it more bluntly, why must horror’s objective worth be gauged by something that is subjective to individual tastes and contexts?

Let me just say up front that if I gauged the success and quality of horror films by how much they could scare me, Paranormal Activity (2007) would be the one and only film on the list of horror flicks that caused me to lose sleep. Sure, I have been unnerved, grossed out, and disturbed by some horror films, but scared? Not really. Matter of fact, the only other films that increase my heart beat at all are 2015’s Creep and 2007’s Zodiac. Yet, I still went to sleep with ease and never once felt the urge to look over my shoulder for the remainder of the night. Only Paranormal Activity has achieved that.

Let me just say up front that if I gauged the success and quality of horror films by how much they could scare me, Paranormal Activity (2007) would be the one and only film on the list of horror flicks that caused me to lose sleep. Sure, I have been unnerved, grossed out, and disturbed by some horror films, but scared? Not really. Matter of fact, the only other films that increase my heart beat at all are 2015’s Creep and 2007’s Zodiac. Yet, I still went to sleep with ease and never once felt the urge to look over my shoulder for the remainder of the night. Only Paranormal Activity has achieved that.

Here is the kicker though. I don’t think Paranormal Activity is necessarily a great film. It’s solid and competent, sure. But great? No. I appreciate its use of practical effects and find them to be overall quite effective in ratcheting up the tension to the point that an otherwise clichéd jump scare ending sent me out into the dark, early morning shaken. To complicate the matrix of “scariness” further, I know very few people who have seen Paranormal Activity and come out of it with the same response. I have heard everything from laughter, annoyance, unabated love, even absolute hatred of the stupidity of the film. This is the crux of the problem I have with using a sliding scale of ‘scariness’ as an accurate and qualitative appraisal of horror cinema. Peoples’ fears (and their individual expressions) are not monolithic, they are just as pluralistic as so many other elements in our current American society.

Horror cinema is one of the oldest forms of cinema. Many historians/critics place the first horror film in 1896 with French filmmaker Georges Melies’ film, Le Manoir Du Diable (aka The Devil’s Castle/The Haunted Castle). It’s no surprise that the earliest horror films were made to experiment with the boundaries of technological creativity. The inventors and innovators of modern day cinema were constantly pressing forward to outline the possibilities of the medium and fantasy/horror allowed them to explore techniques of filmmaking unlike most other genres. Jump ahead to America in the 20s and 30s and one sees the creation of production codes and the complex give and take of Hollywood and proponents of censorship. Horror films have been, simultaneously, on the forefront of questions of censorship and the fringes of moral acceptability for most of their existence, only recently coming into some minor levels of acceptance.

It seems horror’s precarious position between innovation and issues of respectability/morality has created a need to forge acceptance within ‘pure’ cinema–the same ambiguous tension between “movie” and “film” in connotation. It is this precariousness that has led both critics and fans to seek out terminology that accentuates the specific characteristics of the genre (exploitation/exploration of human fear) to make an argument for horror’s existence as legitimate cinema. We accentuate its differences to validate its equal standing on terms of cinematic plurality. As it happens, we, as fans and critics, perhaps over-accentuate the emotional and experiential descriptions of the. This is not to say these experiences and our descriptions of them have not been helpful in finding some levels of acceptability, but they have also backed the innovative and technical qualities of horror cinema into a corner, always in submission to experience.

There are several horror films that have been celebrated on experiential/emotional and technical terms; they fill up many of the best horror film lists out there along with the continual reviews and articles throughout the years, but this acceptance only goes so far in allowing the totality of the horror genre to be taken on its full merits. I am just as much to blame for accentuating the experiential elements as much as anyone. For horror to finally gain a complete acceptance within the world of cinema—maybe even be considered for an Oscar, not that it’s worth that much—the shift needs to take place from the ground, up. Fans and critics need to demote our focus on emotional/experiential elements of horror and seek to appreciate and accentuate horror films on their innovative, creative and technical merits. Appreciate them as film as well as horror. Distinguish their specific space in cinematic pluralism as well as their technical achievement and beauty alongside all other films.

There are several horror films that have been celebrated on experiential/emotional and technical terms; they fill up many of the best horror film lists out there along with the continual reviews and articles throughout the years, but this acceptance only goes so far in allowing the totality of the horror genre to be taken on its full merits. I am just as much to blame for accentuating the experiential elements as much as anyone. For horror to finally gain a complete acceptance within the world of cinema—maybe even be considered for an Oscar, not that it’s worth that much—the shift needs to take place from the ground, up. Fans and critics need to demote our focus on emotional/experiential elements of horror and seek to appreciate and accentuate horror films on their innovative, creative and technical merits. Appreciate them as film as well as horror. Distinguish their specific space in cinematic pluralism as well as their technical achievement and beauty alongside all other films.

On the other side, it is quite easy to see that the hype studios use to get ticket sales and publicity plays into this qualitative matrix as well. Take for instance The Witch, which from the mouths of several critics and general viewers does not live up to the hype of the “scariest movie you will see this year” and other such promotional aggrandizements. I, too, would agree that I was not ‘scared’ by the film, but I did find it unnerving in the same way that 2014’s Under The Skin was. I went home, went to sleep with no problem, suffered no anxiety or fear, but I did think about the movie in the proceeding days. It got under my skin, but it didn’t create goosebumps. However, studios know that if they hype a film up and it gets good critical and public reception then people will take notice and go into the film expecting that sort of experience. It is not unusual to find people, then, coming out of the film feeling cheated, because Robert Eggers’ central goal was not to scare people like the promotional material makes it seem. It seems his aim was more towards providing a powerful and profound historical account of life in 1630s New England that just so happens to involve horror elements.

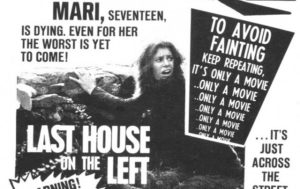

These promotional techniques are nothing new. Making the audience feel like they are supposed to come out of every horror film scared, terrified, etc. is as old as horror cinema. Everything from William Castle’s theatrical gimmicks (vibrating seats in theaters for The Tingler, for example) to Sean Cunningham’s reverse psychological promotion for Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left where he ultimately told people to not go to the film because it is too scary to the more recent “clickbait” versions of horror film promotion. Studios that produce horror fare are equally at fault for making the scariness of a horror film the central focus and thereby forcing the genre into a corner of second-level analysis (“it’s pretty good for a horror film,” etc.). The hype that has always accompanied the promotion of horror films should hardly ever be believed…or used. However, this does not seem to be a trend that will change anytime soon.

These promotional techniques are nothing new. Making the audience feel like they are supposed to come out of every horror film scared, terrified, etc. is as old as horror cinema. Everything from William Castle’s theatrical gimmicks (vibrating seats in theaters for The Tingler, for example) to Sean Cunningham’s reverse psychological promotion for Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left where he ultimately told people to not go to the film because it is too scary to the more recent “clickbait” versions of horror film promotion. Studios that produce horror fare are equally at fault for making the scariness of a horror film the central focus and thereby forcing the genre into a corner of second-level analysis (“it’s pretty good for a horror film,” etc.). The hype that has always accompanied the promotion of horror films should hardly ever be believed…or used. However, this does not seem to be a trend that will change anytime soon.

There are increasing numbers of people that are starting to view horror as cinema/filmmaking, not just entertainment. Critics like Scott Tobias (and most of the contributors for The Dissolve) and Scott Weinberg, to name a few, are not only fans of the genre, but they write in a way that focuses on the technique, composition, cinematography, etc. and, also, how the film was experienced by them, how they emotionally connected to it. There is always the danger of moving too far in the opposite direction where horror is only viewed through its formal cinematic elements and that must be avoided as well. However, horror has never quite crossed that median point onto the other side during its existence, so I don’t have much fear of such over-correction taking place anytime soon.

The main point is that considering its importance within the scope of cinema history, its significant progression of technological innovations and its constant back and forth interactions with production codes, religious institutes and public morality, horror should be taken seriously as film, writ large, and not just as profitable, popcorn entertainment. I do see a severe push for serious analysis and consideration of the genre in the world today and for that I am glad, but we must teach ourselves to hesitate before we base the quality of a horror film on how much it scares us. Instead, we need to realize that whether a horror film scares us is largely subjective to the individual viewer and that those emotions/experiences of a film, though important, should just be the icing on the critical cake.

The main point is that considering its importance within the scope of cinema history, its significant progression of technological innovations and its constant back and forth interactions with production codes, religious institutes and public morality, horror should be taken seriously as film, writ large, and not just as profitable, popcorn entertainment. I do see a severe push for serious analysis and consideration of the genre in the world today and for that I am glad, but we must teach ourselves to hesitate before we base the quality of a horror film on how much it scares us. Instead, we need to realize that whether a horror film scares us is largely subjective to the individual viewer and that those emotions/experiences of a film, though important, should just be the icing on the critical cake.