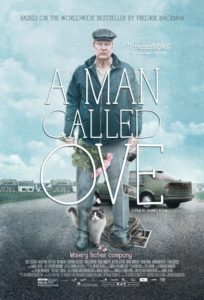

Based on the massively popular book of the same name by Fredrik Backman, A Man Called Ove (2016) is a delightful and charming film—a well-crafted, earnest drama fully deserving of the praise it has received both in its native Sweden and abroad. Ove is centered around its titular character (Rolf Lassgård), a crotchety, elderly widower who patrols his small neighborhood with great vigilance, making sure that the residents maintain an orderly lifestyle. He locks up bicycles kids have left strewn about, picks up the smallest piece of trash, and ensures that no one drives down the pathways he has deemed off-limits. Ove is also preparing to kill himself. He buys the requisite supplies and makes meticulous plans, but before he is able to do the deed he is interrupted by Parvaneh (Bahar Pars), the young woman who has just moved in across the street. She introduces Ove to her husband and son, and as Ove finds himself welcomed into the family, he slowly begins to question his suicidal desires.

Based on the massively popular book of the same name by Fredrik Backman, A Man Called Ove (2016) is a delightful and charming film—a well-crafted, earnest drama fully deserving of the praise it has received both in its native Sweden and abroad. Ove is centered around its titular character (Rolf Lassgård), a crotchety, elderly widower who patrols his small neighborhood with great vigilance, making sure that the residents maintain an orderly lifestyle. He locks up bicycles kids have left strewn about, picks up the smallest piece of trash, and ensures that no one drives down the pathways he has deemed off-limits. Ove is also preparing to kill himself. He buys the requisite supplies and makes meticulous plans, but before he is able to do the deed he is interrupted by Parvaneh (Bahar Pars), the young woman who has just moved in across the street. She introduces Ove to her husband and son, and as Ove finds himself welcomed into the family, he slowly begins to question his suicidal desires.

At first blush, A Man Called Ove sounds like it would be happily at home with the most rote of mainstream hollywood melodramas; and while the film does to a large extent hold fast to some of the dominant tropes of the genre, there are a number of ways in which this film is more commendable than its competitors.

For one, Director Hannes Holm’s arresting mise-en-scène beautifully reifies its protagonist’s subjective inner state. In the film’s first act, for instance, Holms creates symmetrical compositions that mirror Ove’s obsessive-compulsive tendencies; he’ll place a camera in the middle of one of the small roads in Ove’s neighborhoods, and the small houses—which are all virtually identical—fill the left and right thirds of the screen from foreground to background in a most aesthetically pleasing way. And when Ove prepares to kill himself in his living room, the camera frames him within the frame of his oversized glass window. This kind of double-framing gets at Ove’s predilection for order and is simultaneously indicative of the in-betweenness he experiences as he feels called to die (and so join his beloved wife) on one hand, and to go on living in order to retain control of his little community, saving it from the messiness of the new neighbors, on the other. Formally, it’s suggestive of Wes Anderson, minus the polish and shine. But as Ove grows closer to Parvaneh and her family, a very interesting thing happens with Hanne’s compositions: They get messier. He returns to familiar shots, but now a car parked in the middle of the street disrupts the symmetry. Ove’s change of heart is made manifest in physical forms and shapes.

A Man Called Ove is replete with a characteristically dry and dark Scandinavian humor that injects into the film an extra shot of energy and life. Ove’s repeated attempts at suicide are played out with a tremendously comedic effect, as his plans are continually thwarted. And Rolf Lassgård’s performance to this end is spot-on. His ability to contort his face in an awful scowl, to rigidly carry his body in a way that personifies contempt, and to deftly growl lines of reproach is remarkable—as is his more subtle, softer performance in the third act. Even in the moments when the film pushes on the melodrama pedal a little too heavily, Lassgård is there to help pump the brakes and get things headed back in the right direction.

Simple and deeply moving, A Man Called Ove speaks to the transformative power of community and (quite literally) love of neighbor. It’s the tale of a grief-stricken man who was content to patrol the streets and alley of his town, building his own kingdom and writing his own story as he went. It’s about a man who, thanks to the love and care of friends, was inscribed into a new and outward-facing narrative of charity and life.

1 comment