Amarillo, Texas is not one of those places that finds much representation within cinematic landscapes. We are vaguely West Texas in name only so many of us who live in these flatlands look on films like There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men, and Hell or High Water with pride even though that region is hours away from the Panhandle of Texas. Something about the geographic isolation, the line of sight unobscured by concrete and steel and the supposed lack of intrigue or culture—which is perception more than truth—keeps the place where I was raised from getting much notoriety beyond a fatty, grisly piece of steak found on I-40.

Amarillo, Texas is not one of those places that finds much representation within cinematic landscapes. We are vaguely West Texas in name only so many of us who live in these flatlands look on films like There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men, and Hell or High Water with pride even though that region is hours away from the Panhandle of Texas. Something about the geographic isolation, the line of sight unobscured by concrete and steel and the supposed lack of intrigue or culture—which is perception more than truth—keeps the place where I was raised from getting much notoriety beyond a fatty, grisly piece of steak found on I-40.

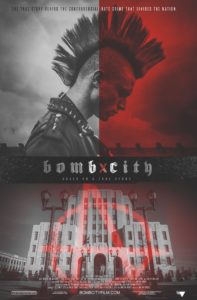

That is until Bomb City, a film about the murder of a young man, Brian Deneke, for living an alternative lifestyle (read: “punk”), by one of his peers, Dustin Camp, a “jock” who towed the social and cultural lines of our local community. It was a news story that escaped the bounds of the Panhandle and got some national attention—so much so that even Marilyn Manson commented on it which the film utilizes in an earlier scene. It gave the rest of the world cognizance of our existence and gave a particular perception of the area that was equal parts true and spin. There is a particularly stalwart and oppressive mix of religious self-righteousness, staunch political ideology and isolationist tendencies that plague these dirt-strewn lands. The “other” is not easily embraced whether it be punks, LGBTQ, or refugees. These things are true, and these are placed in the atmosphere of the film with mixed levels of effect.

The director, Jameson Brooks, and co-writer, Sheldon Chick, are both Amarillo natives and the care given to the feeling of the film along with the exterior shots of Amarillo were nice to see and gave the film a realness that someone not from the area might take for granted. There were shots on the streets of Amarillo that I actually recognized and, regardless of this area’s faults, there was a warmth of seeing it on celluloid. It’s the details of place that make up the film’s strongest element. They were able to give people a since of how a land so open and so flat can often feel so enclosed and captive.

The story itself was and continues to be one of many that highlights how we draw lines between ourselves and others and create illusory understandings of superiority. Sometimes those illusions lead to the point where a person is perceived as less than human and murder becomes a viable reaction against the threat of the other. In our current cultural moment, this is becoming more and more present in our national awareness. Brian Deneke didn’t live by the expectations of the culture of Amarillo and he paid a horrible price. He should not have been outcast from society or killed for being different. This, rightly so, comes to the foreground in Bomb City. It is a narrative line that can gain the compassion of even the most hard-hearted member of our society. This is the driving force behind the film and, on the whole, Brooks and Chick are able to make Deneke relatable and lovable—as many in my community continue to love and remember him. The film showed his imperfections and his creative expression and Dave Davis did solid work of taking on Deneke’s persona.

The story itself was and continues to be one of many that highlights how we draw lines between ourselves and others and create illusory understandings of superiority. Sometimes those illusions lead to the point where a person is perceived as less than human and murder becomes a viable reaction against the threat of the other. In our current cultural moment, this is becoming more and more present in our national awareness. Brian Deneke didn’t live by the expectations of the culture of Amarillo and he paid a horrible price. He should not have been outcast from society or killed for being different. This, rightly so, comes to the foreground in Bomb City. It is a narrative line that can gain the compassion of even the most hard-hearted member of our society. This is the driving force behind the film and, on the whole, Brooks and Chick are able to make Deneke relatable and lovable—as many in my community continue to love and remember him. The film showed his imperfections and his creative expression and Dave Davis did solid work of taking on Deneke’s persona.

The Dustin Camp character, named “Cody Cates,” is where the film fails to live up to the praise Richard Linklater’s gave the film when he hosted its screening in Austin, TX. While the film is and should be on the side of the victim in this story, it doesn’t mean that they should paint Dustin Camp’s character without nuance. The film fails to take into account the thing that our nation is often not taking into account when addressing the wrongs of people on the national stage: there are bigger, more systemic factors that play into individual behavior than just the choices of people like Dustin Camp. Recognizing the complexity of that is not letting Camp off the hook, but recognizing our own part in creating a society and culture where murdering someone because of their differences is a viable option. If the film was going to give any time to Camp’s character, then they needed to give more insight into how he became the person who would do this act of violence. We need to have more than just forlorn parents looking on as the police find blood on Camp’s car. We need to see how the land that Brooks gave so much detail and care in the setting of the film and its particular cultural and social makeup were at fault for Dustin Camp’s murder of Brian Deneke.

It’s these questions that keep Bomb City, while being a solid debut by Jameson Brooks, from reaching levels of the likes of Linklater and Jeff Nichols and others who give complex renderings of communities, morality, and the illusions of control when choices are made. Even with these failures, this Amarillo native was proud to see my homeland on the big screen and would recommend anyone to seek the film out and reflect on how events like this could happen and how we, though not part of the actual incident, are culpable for creating the space in which something like this could take place. It should never happen and it continues daily. Maybe it’s time to ask those harder questions of ourselves and Bomb City is a decent, but flawed, reminder of that.