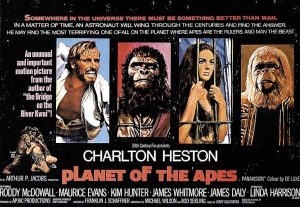

The Redeeming Culture Cinephile is our series about classic films; we hope you enjoy another look at some of the formative films in cinema history.

The recent reboot of Planet of the Apes movies are high-quality, smart, engaging, and consistently well-made. Though a particular film may be weaker, the series as a whole is still solid. Being recent, naturally it’s not at all dated, and here we have the main problem with the 1968 movie The Planet of the Apes.

It is dated.

The original Apes came out on the exact same day as the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which still looks contemporary. That’s a weird movie, but nothing about it announces that it was made in 1968. Planet of the Apes, though, has many earmarks of films made exactly when it was made; most notably the dubious use of the zoom lens, cinema’s new, favorite toy in the late 60s and early 70s. It’s hard not to balk at it. And outer space looks like it does in Superman: The Movie, with lots of obvious lens effects and bright flares floating by. It doesn’t last, but it’s right at the beginning, setting us up for a goofy time.

My point is to point them out so that you can set aside such distractions. Yes, they’re there. Yes, you will notice them for a while. Try to move on, because the film remains a pretty smart, well made movie, even 50 years out.

Intelligence and humanity have a way of never really dating, and these were employed by director Franklin Schaeffner to help us accept the apes as real. He immediately makes them specific characters. The first ones you see act with their eyes. They read immediately likable or dislikable as individuals, this factor covering the few believability issues not conquered by the makeup.

Misanthropy Assumed

Those who know some of the touch points of the film know that we won’t even find the apes for a little while. The reveal is pretty famous, so it may seem like there’s going to be some drudgery, waiting for a secret we already know; but keep in mind that it’s in the title of the movie. People in 1968 knew there would be apes, too. The beginning of the film is not pretending we don’t know what’s coming.

It is introducing the lead character’s bitterness, for one thing. When our movie starts in earnest, the date is November 25th, 3978. Our three living astronauts are roughly 2000 years past the date of their launch from Earth. They crash on a planet, lose their ship to the bottom of the sea, and set out looking for drinkable water. And their leader, Taylor, is a misanthrope and a cynic; and as is common, this makes him a pretty mean person.

It is introducing the lead character’s bitterness, for one thing. When our movie starts in earnest, the date is November 25th, 3978. Our three living astronauts are roughly 2000 years past the date of their launch from Earth. They crash on a planet, lose their ship to the bottom of the sea, and set out looking for drinkable water. And their leader, Taylor, is a misanthrope and a cynic; and as is common, this makes him a pretty mean person.

Landon: But you… You’re no seeker. You’re negative… You thought life on Earth was meaningless. You despised people. So what did you do? You ran out.

Taylor: No, no. It’s not like that, Landon. I’m a seeker too. But my dreams aren’t like yours. I can’t help thinking somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man. Has to be. (much later he adds) Lots of… lovemaking, but no love. That was the kind of world we’d made.

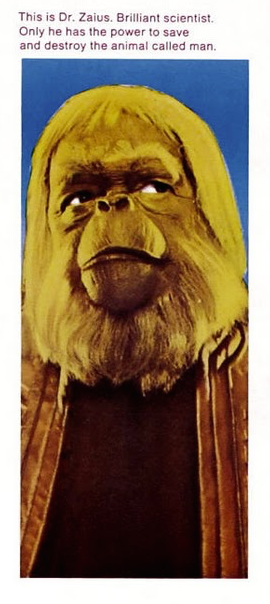

The apes’ Dr. Zaius will express a similar view of mankind in his own world: “The sooner he is exterminated, the better.”

The Smudge on the White Lab Coat

Dr. Zaius represents anyone whose cherished ideas are being challenged, knows that the challenges have merit, and wants to keep that merit out of play. Naturally the erudite, but essentially benighted, characters must be the religious ones; a common myth in our popular fiction. Anytime a movie pits evolution (or more broadly, science) against religion, (in this case, a religion-themed cultural caretaker), we know who is supposed to be the good guy, and who is the bad guy.

Dr. Zaius is the protector of the apes’ religious culture, and he prefers Taylor remain silent, especially after he sees that the man has written real words in the sand (which Zaius quickly erases). When he tells Taylor, “You are a walking pestilence,” he’s not speaking of diseases Taylor might carry, but of his presence, which proves things the Doctor does not want proven.

In addition to erasing the writing, he crushes Taylor’s paper airplane, and at the film’s end, blows up a cave full of evidence of man and apes’ past.  When Taylor’s ability to talk becomes undeniable, he is put on trial to demonstrate his intelligence, this spuriously to be determined by his knowledge of these apes’ particular laws. “He doesn’t know our culture because he cannot think,” Zaius decrees.

When Taylor’s ability to talk becomes undeniable, he is put on trial to demonstrate his intelligence, this spuriously to be determined by his knowledge of these apes’ particular laws. “He doesn’t know our culture because he cannot think,” Zaius decrees.

Sometimes that’s how people try to win arguments. Keep the facts off the table.

Zira: But what about your theory? The existence of someone like Taylor might prove it.

Cornelius: Do you want to get my head chopped off?

Zira: Don’t be foolish. If it’s true, they’ll have to accept it.

Cornelius: No, they won’t.

Apes tries to fall easily into a science vs. religion premise; but in the details, it shoots itself in the foot. Note that the theory promoted by Cornelius is no less silly than the position of Dr. Zaius. Cornelius represents the thinking people on this planet, and he has an evolutionary theory he wants to pursue, via evidence from that doomed cave, located in The (religiously) Forbidden Zone.

Zira: Cornelius has developed the most brilliant hypothesis… That the ape evolved from a lower order of primate, possibly man. In his trip to the forbidden zone, he discovered traces of a culture older than recorded time.

Cornelius: The evidence was very meager.

Zira: You didn’t think so then.

Cornelius: That was before Dr. Zaius and half of the Academy said my idea was heresy.

Zira: How can scientific truth be heresy?

If the one who’s trying to control your mind is the bad guy, then the opposing person is probably correct about their facts, right?

Only maybe. A thing may be declared heresy and still be incorrect. Cornelius has some things backwards, but he’s going with appearances; and we can do that for a long time, especially when we’re selective about what we admit into consideration.

Fortunately, beyond any science vs. religion intent, Apes has deeper things to illustrate. Dr. Zaius is, after all, both the chief defender of the faith and the minister of science.

John 3:20 “Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed.

–John 3:20, NIV

What this movie reveals is a good tell. When one side of an argument shuts down discussion through threat and derision, and the other is opening the dialogue and presenting new evidence, the former is to be suspect. If one has real confidence in a matter, she will be open to discussion and debate; even to the point of accepting that she might be proven wrong, because if her side really has the goods, they’ll be entered and the debate will end. If someone merely proclaims, “The debate is over!” they’d better stand and deliver, because the more reactionary approaches indicate little more than insecurity, and that goes for the science side as well.

No one is above reproach or correction.

Misanthropy Defended

Ecclesiastes 7:20 “…there is not a righteous man on earth who continually does good and who never sins.”

In the end, Taylor and Zaius, with equal disdain for mankind, face off. Each has his good points.

Taylor: All right. If they can prove those scrolls don’t tell the whole truth of your history, if they can find some real evidence of another culture from some remote past, will you let them off?

Zaius: Of course.

Taylor: Cornelius was right, doctor. He proved it. Man was here first. You owe him your science, your culture – whatever civilization you’ve got.

Zaius: Then answer me this. If man was superior, why didn’t he survive? (to Cornelius) …Reach into my pocket. Read to him the 29th scroll.

Cornelius: “Beware the beast man, for he is the devil’s pawn. Alone among God’s primates, he kills for sport or lust or greed. Yea, he will murder his brother to possess his brother’s land. Let him not breed in great numbers, for he will make a desert of his home and yours. Shun him. Drive him back into his jungle lair. For he is the harbinger of death.”

That scroll is not wrong in its characterization. There is a big reversal of expectations here: in the beginning of the movie, Taylor is shown to be a misanthrope, someone who has little belief in the goodness of mankind. Usually this is a setup for someone to learn a lesson, and go through a change to empathy, or small-h humanism. That is not what this movie does. If anything, Apes underlines the fact that Taylor’s opinion was exactly right.

Saved From What?

There is a lot of attempted saving going on in Planet of the Apes. Dr. Zaius is trying to save the apes from a discovery which could lead them in the direction he knows his predecessors went, to total destruction. It’s a bad tactic with a noble goal in mind.

There is a lot of attempted saving going on in Planet of the Apes. Dr. Zaius is trying to save the apes from a discovery which could lead them in the direction he knows his predecessors went, to total destruction. It’s a bad tactic with a noble goal in mind.

Cornelius wants to uncover the truth, without saying this: the truth sets one free. The truth is always the preferable position to be in, in almost any situation. It arms us, and defends us. It’s just natural to want to be in a place of truth rather than a place of lies. He’s not a rebel, just a truth seeker.

But, Dr. Zaius is right; the truth he will discover would probably lead the apes down the exact same path the men went.

So there are forbidden zones. Evidence is destroyed. It would be easy to simplistically lay this on one side of the Dr. Zaius/Cornelius debate, but this movie shows that there is not enough good in any of these people. There is integrity in bad Zaius’s trying to keep his people safe; there are deep flaws in the theory for which good, truth seeking Cornelius wants his evidence. Individuals have some nice qualities, but also great failings; and as a whole, nothing these people do will save them from their future.

One could say that, artistically, maybe Taylor was supposed to be a sort of a Christ figure. He comes down to Earth out of the sky, wanders in the desert, and is tormented by captors who aren’t actually as advanced as he is; though they think they’re better.

Okay, it’s an easy, common read. But in Planet of the Apes, Taylor’s arrival will not, and cannot, lead anywhere good. He has no interest in saving these people from anything. He has no higher goal than getting away from them, and being on his own. Not much of a savior. He sees the world as a rotten place, filled with rotten beings. Even the friendly ones probably aren’t going to make things turn out all that well – and he is also a rotten person, who just wants to be away from them.

The condition of man is pretty much as Planet of the Apes paints it. There are a lot of nice people, a lot of thinking people, but enough of what we do and are is flawed. And, contrary to the opinion of, say, Star Trek, that is not one of humanity’s charms; it is one of our downfalls. Always has been, always will be. We muddle about, and we’re basically able to tread water, morally and socially, but aside from being able to do a new and exciting things with metal, we haven’t really progressed, certainly not in any ‘goodness’ way.

…one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die—but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

–Romans 5:7-8, NIV

Reality Steps In

Fortunately, in the real world we have an actual savior: a good Person, truthful, able, and well-intentioned toward us in spite of Himself. The gospel is an interesting thing. Christians refer to being saved, and saving souls, and the word salvation is tossed about, and it would be a reasonable question for an outsider to say, “Saved from what, exactly? Or from whom?”

[pullquote]Yes, saved from the good guy, by the good guy.[/pullquote] The answer is, saved from God. Yes, saved from the good guy, by the good guy. The message of the Gospel is that we have a Creator who is good, who made things which were good, who made us able to do and be good; and we (both through a representative and as individuals) did (and do) willfully turn away from that.

We are the coffee maker that no longer makes coffee, or the computer program that isn’t doing what it’s supposed to do when you press the exact button you’ve been told to press. We’ve all had experiences where we are doing exactly the right thing, and the expected, right response is not happening, and we get justly angry. We throw things away that don’t work.

Taylor: God, damn you all to Hell!

Those are reductive examples, but we are the created beings that do not do what we’re supposed to do. You can read the historical accounts of the things Jesus said and did, and you’ll see quite a lot of finger-pointing on his part. And he’s right. It’s accurate finger-pointing.

But that is only step one, not the final step. Unlike Taylor, or Zaius, our savior did not come down to ultimately condemn us. That is just his illustrating that these are the things from which we need to be saved. Ourselves: how we treat each other; God: how we treat the One who made us. Saved from God’s well deserved anger and dismissal, that’s what Christians mean when they use their shorthand. It is a part of God’s justifiable attitude toward those he created

Enter not into judgment with your servant, for no one living is righteous before you.

–Psalm 143:2

But he does not throw us away. He does not even necessarily leave us in our own muck, to allow natural consequences to punish us for our own actions and inactions.

Something needs to be thrown away. So, though he is actually perfect and good, he is the one that gets thrown away, and he takes care of that himself. He is the one whose life gets lost because we won’t function properly. And His promise is to rescue us, not just from ourselves, not from each other, but from his own justice; and to do that not only fully, but even reversing it.

[pullquote class=”left”]It’s actually a reward. We will finally be able to be and do the good that we have been made to be and do, that we can imagine must be right, and always long to see.[/pullquote]This is not just a leveling off, a reset to zero; it’s actually a reward. We will finally be able to be and do the good that we have been made to be and do, that we can imagine must be right, and always long to see; usually in others first, and when we’re honest, in ourselves too.

We’re being given a thirst for what is right, as a contrast to what we live in. When what’s right fully arrives, we will be able to get along with all of the people we’ve never been able to get along with. We will be willing to face truths we’ve never wanted to let in because their truthfulness will matter more to us than prior, misguided commitments. We will appreciate God as we should, without trying to mold him into things he isn’t. Those are only some of the very few benefits of the real place called Heaven. Don’t they sound just right?

Once we believe that he was who he said and demonstrated he was (which demonstration, history, and reason back up quite solidly), recognize our part in that equation (as the offenders, summarily and individually), and accept what he did he did on our behalf for us (receiving his gift of salvation), we are no longer destined to be left on The Planet of the Apes.

• • •

Thanks for reading. The Redeeming Culture Cinephile seeks to examine the classics of film history through a culture-redeeming lens. Read more reviews of classic flims here.

Here’s another perspective on Apes, all five of the original Apes movies, in fact, from someone who goes further back than I do. Just on the level of helping us get past the past-ness of these, and seeing how they could have had some value beyond being silly entertainments, it’s a nice piece to see.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m9QZAjMQsWA