Sacred books and texts loom large in human civilizations, past and present. Yet such books and texts are scarce in Star Trek. Memory Alpha’s entry on “Sacred Texts” lists exactly 16 examples from the entire franchise.

Is this dearth of sacred books another example of Star Trek’s widely assumed indifference (at best) or antagonism (at worst) to religion? Does the franchise see such texts as only negative influences on a civilization?

Three episodes of the original Star Trek series (TOS) feature sacred books or texts in notable ways. Taken together, these episodes suggest books and texts regarded as sacred can shape civilizations in positive ways—when correctly interpreted.

The Book of the People

“For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”

“For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”

The Book of the People is the sacred text of Yonada, the asteroid generation ship carrying the Fabrini people on a collision course for planet Daran V. The Book is so holy, it is quite literally “set apart” from the Fabrini: usually hidden from sight in an obelisk, and not to be opened or read until Yonada reaches the destination its creators chose.

The Fabrini lack direct access to The Book’s text. The Oracle (the computer controlling Yonada) mediates knowledge of it to Natira, the people’s high priestess. She, in turn, mediates knowledge of The Book, which not even she has read, to the Fabrini. Neither she nor her people nor we actually know what is written in this text. And as viewers, all we know for certain it contains is instructions for opening the Oracle’s altar, which Kirk and Spock find and use to enter Yonada’s control room and correct its course.

Is The Book actively shaping Fabrini civilization? We cannot be certain. Assuming the Oracle conveys accurate knowledge of its contents to Natira, and assuming she accurately relays her knowledge of what is written to the people, it is, at least indirectly.

Is The Book actively shaping Fabrini civilization? We cannot be certain. Assuming the Oracle conveys accurate knowledge of its contents to Natira, and assuming she accurately relays her knowledge of what is written to the people, it is, at least indirectly.

But we can be certain the Fabrini’s extreme reverence for The Book is literally risking their civilization’s life. Without Kirk and Spock’s intervention, the Fabrini would have died along with the population of Daran V merely because no one would have opened The Book to discover the truth of their situation or how to enter Yonada’s control room.

In the end, this episode makes an apparently mundane assertion about this sacred text: It contains life-giving information, but that information can do no one any good when no one is reading the text. (Yet a similar conclusion helped power the Protestant Reformation and its antecedent movements, so perhaps it is not as mundane as it first appears.)

Eed plebnista

(“The Omega Glory”)

On Omega IV, in a parallel development Spock calls “almost too close,” Earth’s own 20th-century conflicts between the United States of America and Asian Communist nations (China, North Korea, North Vietnam) played out in a different way. As Kirk sums up the situation, “The yellow civilization is almost destroyed, the white civilization is destroyed.”

“The Omega Glory” is an offensive episode at almost every turn. Its parallel Earth premise offends viewers’ intelligence, but is the least of its offenses. Its caricatures of Asians; its one-to-one conflation of Christianity with American patriotism; its explicit erasure of all non-white Americans (per Kirk, the U.S. is identified as “the white civilization”), its faux-indigenous American clothing and speech patterns for the Yangs, whom Kirk asserts are “fighting to regain their land,” when the Earth “Yanks” they parallel stole lands from indigenous peoples—all these elements lay bare the Cold War privileges and prejudices of white Americans, especially white American Christians, which persist even today.

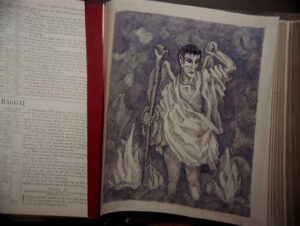

But if we can set aside the episode’s racism and jingoism for a time, we’ll find a positive statement about sacred texts’ capacity to shape a civilization in constructive ways. For the Yangs regard as their “holiest” text the Eed plebnista, which is actually a verbatim, independent emergence of the U.S. Constitution (presumably; we at least know it contains the Preamble with which we are familiar). The Yangs have at least two other sacred texts—Aypledgli ianectu flaggen, which is the Pledge of Allegiance to the U.S. flag; and the Bible (though perhaps with reordered contents, since its Book of Haggai appears near the book’s beginning, illustrated with a full-page engraving of a demon who inconveniently bears an uncanny resemblance to Spock.)

But if we can set aside the episode’s racism and jingoism for a time, we’ll find a positive statement about sacred texts’ capacity to shape a civilization in constructive ways. For the Yangs regard as their “holiest” text the Eed plebnista, which is actually a verbatim, independent emergence of the U.S. Constitution (presumably; we at least know it contains the Preamble with which we are familiar). The Yangs have at least two other sacred texts—Aypledgli ianectu flaggen, which is the Pledge of Allegiance to the U.S. flag; and the Bible (though perhaps with reordered contents, since its Book of Haggai appears near the book’s beginning, illustrated with a full-page engraving of a demon who inconveniently bears an uncanny resemblance to Spock.)

Until Kirk can interpret it for them, Eed plebnista is not shaping Yang society. As Kirk tells Cloud William, “I did not recognize [the Constitution’s words], you said them so badly, without meaning.” Here is Kirk’s hermeneutical key: Eed plebnista’s “worship words” about liberty and freedom may as well be the incomprehensible gibberish Cloud William solemnly intones so long as the Yangs are not embodying them. Unless its readers strive to make these words of freedom apply to everyone—not only “Chiefs” but “all the people;” not only the Yangs “but the Kohms as well”—the words “mean nothing,” as Kirk claims.

As originally written, of course, the Constitution, with its “three-fifths” circumlocutions about enslaved people, failed to live up to its own stated ideals. But, as Kirk recognizes, those ideals are stated, and the document can still inspire and empower a greater faithfulness to them than even the Framers’ generation achieved. This text the Yangs regard as sacred will only be worthy of reverence when they treat it as more than a cherished relic which only the Chief may recite, but a living framework for continuing to build “a more perfect” society.

Chicago Mobs of the Twenties

(“A Piece of the Action”)

(“A Piece of the Action”)

Of these three sacred books in TOS, Chicago Mobs of the Twenties—a book left behind on Sigma Iotia II a century earlier by another starship from Earth, the Horizon—is the clearest example of a sacred text’s power to shape a civilization.

Viewers have no direct access to Chicago Mobs’ text (the page we see onscreen is from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night; we can only play along). Jojo Krako paraphrases two of its precepts: “You make hits. Somebody argues, you lean on ‘em.” But its straightforward title and the society the Iotians built around it indicate it’s a non-fictional account of how criminal gangs, in Kirk’s words, “nearly took over” Chicago in the 1920s when “conventional government almost broke down.”

McCoy calls Chicago Mobs the Iotians’ “Bible.” The planet’s warring territorial “bosses,” at least, afford it that level of respect and reverence. (How average Iotian citizens feel about Chicago Mobs goes unexplored.) Both Krako and Bela Oxmyx keep large, elaborately bound copies on lecterns. When Kirk calls it “a book,” Oxmyx corrects him: “The Book.” We can all but hear the capital letters.

How did Chicago Mobs achieve this pride of place? Although Kirk notes the Horizon contacted Sigma Iotia II “before the Non-Interference Directive went into effect,” it seems implausible the Horizon’s crew intended to “contaminate” the planet. Oxymyx tells Kirk the Horizon left behind other books—“textbooks on how to make radio sets and stuff like that.” We may infer the Horizon wanted to give the Iotians’ then-fledgling industrial civilization a “helping hand” in moving toward the Horizon’s own present. Chicago Mobs did not become the society’s near-sacred “blueprint” simply because it came from the Horizon.

As Earth’s (and the Church’s) histories too often show, “helping hands” can spell disaster and destruction for those being “helped.” The Iotians—or at least those in positions of power—made Chicago Mobs their civilization’s behavioral standard. A century later, that decision has led the society to the cusp of, in Spock’s words, “total anarchy.” Why was it made in the first place?

As Earth’s (and the Church’s) histories too often show, “helping hands” can spell disaster and destruction for those being “helped.” The Iotians—or at least those in positions of power—made Chicago Mobs their civilization’s behavioral standard. A century later, that decision has led the society to the cusp of, in Spock’s words, “total anarchy.” Why was it made in the first place?

The episode doesn’t tell us, but we may infer the vision of civilization found in Chicago Mobs appealed to the Iotians. They read and responded to its depiction of competing bosses with their hit men and molls. Perhaps Chicago Mobs presents a romanticized view of “old Chicago” (as “A Piece of the Action” does), and the Iotians found the prospect of talking and walking like larger-than-life versions of Al Capone, John Dillinger, and others too irresistible (as Kirk and Spock do).

Chicago Mobs elevated itself above all other texts, capturing Iotian imagination and allegiance on its own merits. It became the social standard to be adhered to in all particulars—“The Book tells us how to handle things” (Krako)—and, when necessary, defended: “I don’t want any more cracks about The Book!” (Oxymx).

But even as Oxmyx reveres Chicago Mobs, he seems aware it will ultimately fail his planet if he and the other bosses continue to obey it slavishly. He laments, “I’m a peaceful man at heart, but I’m sick and tired of all these hits… We can’t get anything done.” Because the competing bosses are constantly engaged in violence against each other, they’re not providing the services the planet’s citizens expect in return for paying their “percentages.” Oxmyx is articulating his perception that “The Book” he reveres has its limits. As he reads it, it cannot point its adherents toward a more peaceful and productive future.

Given Kirk’s penchant for challenging and exposing belief systems he deems erroneous and harmful, viewers might expect him to tell Oxmyx and the other bosses to throw The Book out. But as he did on Omega IV, he interprets the sacred text in a new, potentially more productive way. Kirk’s plan to bring Iotian civilization back from the brink—leveraging Federation might to establish Oxmyx as “the top boss” in a new global syndicate from which the Federation will annually collect a “reasonable” 40% “cut”—draws directly from the social vision presented in Chicago Mobs.

Given Kirk’s penchant for challenging and exposing belief systems he deems erroneous and harmful, viewers might expect him to tell Oxmyx and the other bosses to throw The Book out. But as he did on Omega IV, he interprets the sacred text in a new, potentially more productive way. Kirk’s plan to bring Iotian civilization back from the brink—leveraging Federation might to establish Oxmyx as “the top boss” in a new global syndicate from which the Federation will annually collect a “reasonable” 40% “cut”—draws directly from the social vision presented in Chicago Mobs.

Oxmyx and the other bosses treat the concept of a syndicate as a new idea, but it could have come straight from The Book’s pages. The “Chicago Outfit,” “one of the most powerful crime syndicates in American history” according to the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, was consolidating power in Chicago by 1925.

If we take seriously Krako’s assertion that “the Book tells [the Iotians] how to handle things,” we could conclude Chicago Mobs doesn’t discuss criminal syndicates—an implausible omission in a book as thick as it is. We can more confidently conclude the Iotian bosses accidentally or willfully ignored The Book’s content about syndicates, which led them to run the planet “like a piecework factory” instead.

As with Eed plebnista, then, Chicago Mobs contains within it at least the seeds of a better civilization, if not an outright social solution that had been overlooked. What Oxmyx and the others need is not a new book, but a new perspective from which to read their Book—a perspective Kirk is happy to provide.

Some Suggested Applications for Biblical Interpretation

It seems plausible TOS’ creative team intended viewers to take all three of these sacred texts as analogs for the Bible. And perhaps they did so to suggest the problems of basing one’s civilization on a single religious book. The Book of the People is so highly revered as to be rendered useless. The Eed plebnista has become so garbled in transmission as to be nothing more than an artifact. And Chicago Mobs of the Twenties offers a violent and lawless vision of society any sane civilization would surely want to avoid.

Christian Star Trek fans could choose to take each of these episodes as reactions to and rejections of our belief that the Bible is—to some extent or other, depending upon one’s tradition—the Word of God, not only authoritative for the church’s faith and practice but also relevant to the project of human civilization. Christians have differed and still differ about the extent to which society should be “based on” the Bible; however, I suspect few Christians would assert the Bible has nothing to say about how human society should be organized and conducted.

Christian Star Trek fans could choose to take each of these episodes as reactions to and rejections of our belief that the Bible is—to some extent or other, depending upon one’s tradition—the Word of God, not only authoritative for the church’s faith and practice but also relevant to the project of human civilization. Christians have differed and still differ about the extent to which society should be “based on” the Bible; however, I suspect few Christians would assert the Bible has nothing to say about how human society should be organized and conducted.

But I suggest these three TOS episodes give Christian Star Trek fans, at least, valuable insights to bear in mind as we read the Bible.

From the Yonadans’ experience, we can learn that we must not revere the Bible so much that we fail to read it. We must not treat the Bible as so holy that it becomes an object of worship in and of itself. It contains information we need to know, even information we ignore at our peril, and all Christians must be familiar with its contents. Priests and preachers—who, like Natira, mediate the sacred book by virtue of their office—must first proclaim what the text says before interpreting its message; every Christian must read the text’s actual words before discerning how those words apply to their lives and their society.

From the situation on Omega IV, we can learn that empty recitation of the Bible’s actual words can devolve into so much nonsensical gibberish if we do not conduct ourselves according to its standards. We can heed the apostle Paul’s teaching that, without love, Christian proclamation is not proclamation at all, but “a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13.1). If we do not live as though God’s words of freedom and liberty (not to be subordinated to the Constitution’s, as they were on Omega IV) are for all people, then they are just words. Christians in the U.S. can further learn we must hold our own society accountable to its own “worship words” about justice, equality, and peace. We recognize these “worship words” come from a flawed document that does not fully live up to them even in its own original text. We urge our leaders, fellow citizens, and ourselves to strive to embody them not because the Constitution is divine, but because God calls the church to promote justice and peace for all people in this life, not only in the next. God wills human authorities to take “pity on the weak and the needy,” redeeming them from “oppression and violence” (Psalm 72.13-14), and we 21st-century Christians who are in a position (as our first-century forebears were not) to raise our voices and exert our influence toward those goals must do so.

From the situation on Omega IV, we can learn that empty recitation of the Bible’s actual words can devolve into so much nonsensical gibberish if we do not conduct ourselves according to its standards. We can heed the apostle Paul’s teaching that, without love, Christian proclamation is not proclamation at all, but “a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13.1). If we do not live as though God’s words of freedom and liberty (not to be subordinated to the Constitution’s, as they were on Omega IV) are for all people, then they are just words. Christians in the U.S. can further learn we must hold our own society accountable to its own “worship words” about justice, equality, and peace. We recognize these “worship words” come from a flawed document that does not fully live up to them even in its own original text. We urge our leaders, fellow citizens, and ourselves to strive to embody them not because the Constitution is divine, but because God calls the church to promote justice and peace for all people in this life, not only in the next. God wills human authorities to take “pity on the weak and the needy,” redeeming them from “oppression and violence” (Psalm 72.13-14), and we 21st-century Christians who are in a position (as our first-century forebears were not) to raise our voices and exert our influence toward those goals must do so.

And from Chicago Mobs of the Twenties, we can learn the Bible’s vision of society need not be replicated in every detail today—as though it could be—nor rejected outright because it reflects civilization of several thousand years ago. Instead, we can find enduring principles to order human life that remain consistent with God’s will without Iotian-style mimicry of “Bible times.”

I’m aware these suggestions for interpretation are themselves open to interpretation. What constitutes respect and disrespect of the Bible? What are freedom and liberty, as defined by God? How do we discern God’s will, or what biblical content is time-bound and what is timeless?

That’s why we, like the new civilizations in these three episodes, would do well to seek our own “Captain Kirk.” We need the benefit of perspectives and experiences other than our own when interpreting Scripture. We need that outside, different hermeneutical lens. We may not ultimately agree with what our “Captain Kirks” tell us—we are not, after all, living in scripted, hour-long TOS episodes—but if we don’t actively seek other vantage points, we may fall into the interpretive traps we wish to avoid. This is one reason Christians in several traditions offer a “Prayer for Illumination” before reading Scripture, asking the Holy Spirit to guide our reading and speak through Scripture’s words to us in new ways. But the Spirit, blowing where the Spirit wills, can and does also guide and speak through other people, including those who hail from “strange new worlds” outside our own.

That’s why we, like the new civilizations in these three episodes, would do well to seek our own “Captain Kirk.” We need the benefit of perspectives and experiences other than our own when interpreting Scripture. We need that outside, different hermeneutical lens. We may not ultimately agree with what our “Captain Kirks” tell us—we are not, after all, living in scripted, hour-long TOS episodes—but if we don’t actively seek other vantage points, we may fall into the interpretive traps we wish to avoid. This is one reason Christians in several traditions offer a “Prayer for Illumination” before reading Scripture, asking the Holy Spirit to guide our reading and speak through Scripture’s words to us in new ways. But the Spirit, blowing where the Spirit wills, can and does also guide and speak through other people, including those who hail from “strange new worlds” outside our own.

Finally, I suggest we remember Star Trek’s insistence that a text is not ultimately sacred in and of itself, but in the way in which those who read it embody it in their civilization. For all our differing doctrines of biblical inspiration, all Christians confess the Word of God became, not a book, but a person. Jesus Christ is the Word of God, whom we do not know apart from Scripture, but who is by no means confined to it. The Word of God is not bound (2 Timothy 2:9)—not even between the covers of our sacred book.