When you think of Joan of Arc and the movies, which film comes to mind? For many cinephiles, the quintessential Joan film is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc (read Josh Crabb’s review for Dreyer’s film here). Crafted only a few years after her canonization as a saint, Dreyer’s film has been recognized not only as an excellent historical look at the Maid of Lorraine but an emotionally affecting and timeless masterpiece of film.

When you think of Joan of Arc and the movies, which film comes to mind? For many cinephiles, the quintessential Joan film is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc (read Josh Crabb’s review for Dreyer’s film here). Crafted only a few years after her canonization as a saint, Dreyer’s film has been recognized not only as an excellent historical look at the Maid of Lorraine but an emotionally affecting and timeless masterpiece of film.

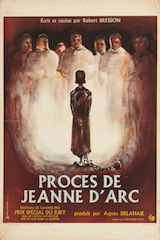

Robert Bresson’s The Trial of Joan of Arc is only similar to Dreyer’s film in the historical setting, not in the formal approach. The 1962 film is composed of static, medium shots of people talking, following the sequential moments within Joan’s trial at Rouen. The film opens with the shot of feet walking down a hallway (a Bressonian touch), which are revealed to be Joan’s mother advocating on behalf of her daughter twenty-five years after Joan’s execution at the hands of the Catholic Church. What follows is the same trial setting as Dreyer, only stretched out as to be more historically accurate (her trial lasted 5 months, not the single day depicted by Dreyer).

The Trial of Joan of Arc is barely an hour in length, and there are no interludes; scenes are cut short abruptly, set end to end without obvious emphasis. The deadpan tone is a striking contrast to Dreyer’s overly emotive scenes. Susan Sontag writes, “There is art that involves, that creates empathy. There is art that detaches, that provokes reflection.” Dreyer is the former, while Bresson’s approach is the latter, using a form “designed to discipline the emotions at the same time that it arouses them.” Where Dreyer fosters intimacy, Bresson creates distance between the viewer and Joan, notably through showing her from the point of view of priests and guards peering at her through a hole in the wall of her prison cell. “By repeatedly filming Joan through the keyhole of her cell, Bresson piques a desire for intimacy that he leaves tantalizingly unfulfilled and forces viewers to share the frustrated voyeurism of the English guards.”

Bresson’s Joan is aloof, both in the film and historically. A close-up of the scribe’s hand that stops recording the trial is indicative of Bresson’s approach: the historical gap between Joan and us is too wide to ever fully know the true saint. Paul Schrader compares Dreyer and Besson in his book, Transcendental Style in Film:

Dreyer’s film is a passion: Bresson’s is a trial. Both depict the historical Joan, but whereas Dreyer emphasizes…the psychology of her existence, Bresson emphasizes the physiology of her existence. Both Joans are alienated, but whereas Dreyer’s Joan is reactive to her social surroundings, Bresson’s Joan is a solitary soul, responding primarily to her voices. Both films reveal the sainthood of Joan: Dreyer through her humanity, Bresson through her divinity. Both view Joan as a suffering intercessor between God and man: Dreyer as the crucified, sacrificial lamb, Bresson as the resurrected, glorified icon.

Dreyer’s film is a passion: Bresson’s is a trial. Both depict the historical Joan, but whereas Dreyer emphasizes…the psychology of her existence, Bresson emphasizes the physiology of her existence. Both Joans are alienated, but whereas Dreyer’s Joan is reactive to her social surroundings, Bresson’s Joan is a solitary soul, responding primarily to her voices. Both films reveal the sainthood of Joan: Dreyer through her humanity, Bresson through her divinity. Both view Joan as a suffering intercessor between God and man: Dreyer as the crucified, sacrificial lamb, Bresson as the resurrected, glorified icon.

Why would you bother watching a Joan of Arc film so similar to Dreyer’s affecting portrayal, yet with an unemotional and enigmatic tone? Perhaps the strength of Bresson’s film is precisely due to its difference. Dreyer’s intention was to create audience empathy, to invite them into Joan’s own struggle and force the audience to face their spiritual trials. Bresson’s diametrically opposite approach is just as difficult to endure, but for the opposite reason—he actively spurns audience empathy. For me, it is akin to the immanence and transcendence of God, with Dreyer’s approach parallel to the former and Bresson as the latter. God is both accessible and unapproachable, the intimacy of Emmanuel and the unspeakable holiness embodied in the nominal tetragrammaton.

This raises another question for me: Why are there so many films about Joan of Arc? She is second only to Jesus as a religious figure depicted within the film. Why does a French teenage girl from the fifteenth century continue to captivate the artistic and cultural imagination, especially from renowned directors like Dreyer and Bresson, as well as George Melies, Cecil B. DeMille, Victor Fleming, and Jacques Rivette? Perhaps the depictions of Joan reveal just as much about the cultural context and personal intent of the author as they do about the historical Maid. Leaving behind no relics of her own, the Joan films serve as her saintly relics, allowing contemporary audiences to share in her journey and potentially glimpse the transcendent through the genre of hagiography on film. Joan of Arc is traditional and radical, feminine and androgynous, a martyr and a maid, a soldier and a saint. She is whatever symbol the filmmaker (and audience) needs and wants her to be.

- Susan Sontag, “Spiritual Style in the Films of Robert Bresson,” in Robert Bresson, ed. James Quandt (Toronto: TIFF Cinemateque, 2011), 55.

- Sontag, 57

- Leen Engelen and Roel Vande Winkel, eds., Perspectives on European Film and History (Gent: Academia Press, 2007), 60.

- Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).