If much in the world were mystery the limits of that world were not, for it was without measure or bound and there were contained within it creatures more horrible yet and men of other colors and beings which no man has looked upon and yet not alien none of it more than were their own hearts alien in them, whatever wilderness contained there and whatever beasts.

“You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it.” –

– Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West

I am afraid of open spaces in the pitch black of night. Highways–which offer connection and commerce during the daytime–become isolating and create ample opportunities for funhouse rides showcasing the unknown terrors that lurk in the dark. I am fully aware that I may be in the minority with this specific fear, but, as I drive the 15 miles from the city to the small college town where I live, the thoughts come of their own free will. And I wonder, just wonder, what lies in those open plains to the right and left of me. I expect something to materialize out of the dark void onto the road in front, to the side or behind me. You see, the reason I fear it is because the threat can come from any direction or all directions at once. At least with an intruder in one’s house, it gives the advantage to the people living there in that they know the layout and constraints of said threat’s movements and cover. That security is nonexistent out there.

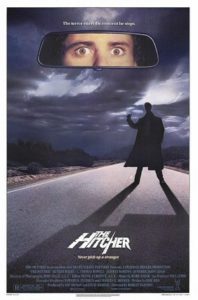

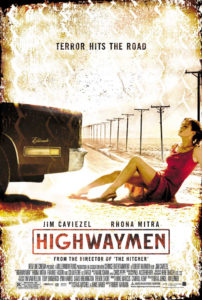

Robert Harmon is the only director I know which has been able to embody that terror of being in the open, shrouded in darkness, and bring that animalistic fear into the light of day. The name may not ring a bell, but I assume anyone with even a moderate knowledge of film knows his 1986 film, The Hitcher, with Rutger Hauer, C. Thomas Howell and Jennifer Jason Leigh. To a much lesser extent, people will know of his 2004 film, Highwaymen, starring Jim Caviezel, Rhona Mitra and Frankie Faison. The former plays more tightly to the strict categories of horror while the latter plays more as a vengeance film with occasional nods to horror. However, both excel at putting flesh on our complete inability to fully know, understand and control the forces that lie in wait just on the horizon, where the sun kisses the glistening black asphalt.

Robert Harmon is the only director I know which has been able to embody that terror of being in the open, shrouded in darkness, and bring that animalistic fear into the light of day. The name may not ring a bell, but I assume anyone with even a moderate knowledge of film knows his 1986 film, The Hitcher, with Rutger Hauer, C. Thomas Howell and Jennifer Jason Leigh. To a much lesser extent, people will know of his 2004 film, Highwaymen, starring Jim Caviezel, Rhona Mitra and Frankie Faison. The former plays more tightly to the strict categories of horror while the latter plays more as a vengeance film with occasional nods to horror. However, both excel at putting flesh on our complete inability to fully know, understand and control the forces that lie in wait just on the horizon, where the sun kisses the glistening black asphalt.

Perhaps the real impressive aspect of a Harmon road film is that the terror it portrays is shown to be human (or, at least, once was). There is nothing seemingly supernatural on the surface. The Hitcher‘s John Ryder is a psychopathic killer who hitches a ride with people only to dispose of them. When one such individual escapes the fate Ryder intended for him, Ryder brings him into a game of cat and mouse. He draws Howell’s Jim Halsey out by playing on his conscience. Halsey comes to find that doing the right thing isn’t easy and will probably kill you and the people around you. In Highwaymen, Caviezel’s James ‘Rennie’ Cray is stalking the mysterious driver who intentionally ran down his wife on the open highway. Fargo, as he is called, is human, but is so handicapped that he modified a ’72 El Dorado to accommodate and ends up really becoming, mechanically, part of the car. The car is this slasher’s weapon of choice. In both films, the motivations of the killers are only explored sparingly, if at all.

Harmon’s vision in both films is raw and visceral. The natural surroundings, the black asphalt and the human menace bleed into and out of each other. As Jim Halsey and Rennie Cray travel the highways that spiderweb across the various landscapes of the American continent, it is not unusual for their antagonizers to pull onto the highway behind them as they trailblaze their own dark paths–not constructed or controlled by human systems. Ryder kills and uses the vehicles. He is a chameleon. By halfway through the film, Halsey realizes that Ryder could be the driver of any vehicle on the highway if he is even allowing for human constructs to dictate his movements.

Harmon’s vision in both films is raw and visceral. The natural surroundings, the black asphalt and the human menace bleed into and out of each other. As Jim Halsey and Rennie Cray travel the highways that spiderweb across the various landscapes of the American continent, it is not unusual for their antagonizers to pull onto the highway behind them as they trailblaze their own dark paths–not constructed or controlled by human systems. Ryder kills and uses the vehicles. He is a chameleon. By halfway through the film, Halsey realizes that Ryder could be the driver of any vehicle on the highway if he is even allowing for human constructs to dictate his movements.

Fargo, however, gives life to his car. It only has one headlight and it is scraped up and dented, much like the man behind the wheel. The car is the mechanical incarnation of the man who wields it. Unlike Ryder, he abides by the constructed system of highways only to baptize the miles of asphalt with the blood of those who drive alongside him. He works within the socially constructed controls over nature, over the chaos of the world, that the American highway system symbolizes. He stays on the man-made roads, Ryder moves freely on and off as is his wont.

Both Ryder and Fargo manifest like ghosts out of the gasoline-infused, sun-drenched, hallucinogenic sightlines where horizon and pavement meet. Vague and opaque, becoming clearer as their silhouettes gradually become harder lines with an evil gleam radiating off of them. They are simultaneously human and other according to the visual cues of the film. They are nature’s embodiment seeking to destroy the systems men put in place to tame and control it. They seek to wash the asphalt with the blood of those who are corporately responsible for its presence. In a sense, Ryder and Fargo are agents of nature, both in the physical sense and in the sense of the human hearts that harbor dark potentials.

They are nowhere and everywhere. Coming from all directions. They only appear when they mean to be seen. In this sense, they are both well within the scope of horror. Revelation from out there is a staple of the horror genre. In the case of The Hitcher and Highwaymen, the revelation speaks to the spaces that humanity inhabits and seeks to control and reminds us that those systemic controls are created illusions which are overturned by nature and those people who refuse to have their behavior dictated by man-made rules. The more malevolent implication of both films is the realization we come to when faced with this revelation. In order for Halsey and Cray to stop Ryder and Fargo’s reigns of terror, they nearly become that which they fight and aim to kill.

They are nowhere and everywhere. Coming from all directions. They only appear when they mean to be seen. In this sense, they are both well within the scope of horror. Revelation from out there is a staple of the horror genre. In the case of The Hitcher and Highwaymen, the revelation speaks to the spaces that humanity inhabits and seeks to control and reminds us that those systemic controls are created illusions which are overturned by nature and those people who refuse to have their behavior dictated by man-made rules. The more malevolent implication of both films is the realization we come to when faced with this revelation. In order for Halsey and Cray to stop Ryder and Fargo’s reigns of terror, they nearly become that which they fight and aim to kill.

There is moral quandary that arises in these films: in order to stop these killers–personified harbingers of chaos and evil out there–Halsey and Cray must become Ryder and Fargo. Once this happens, Ryder and Fargo have won, they have brought these men out of the “Platonic cave” into the reality of the world, of nature. Even if they die, they die knowing that the man standing before them is a new creature, bound up in the chaos and violence of the open road. Baptized in the darkness.

Harmon’s films take meditative look at the forces that rule this world and the human psyche and display them viscerally on a Grand Guignol stage of dirt and asphalt in broad daylight. Motives are incidental to Ryder and Fargo, which makes them strike an otherworldly figure much like The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. They are shaping the world into their image, that of chaos and violence, and those who come up against them either become like them or accept the cost of coming up against such forces and become roadkill knowing full well that this battle is bigger than they are.

My fears of open spaces in the dark of night may be largely irrational, but The Hitcher and Highwaymen assure me that something is out there whether I can understand or control it or not. When it flanks us from all sides, we find ourselves at a precipice: one horizon promises to make us into a new creature, the other horizon will make us into a new creation. And the highway stretches ever so long in between them.

My fears of open spaces in the dark of night may be largely irrational, but The Hitcher and Highwaymen assure me that something is out there whether I can understand or control it or not. When it flanks us from all sides, we find ourselves at a precipice: one horizon promises to make us into a new creature, the other horizon will make us into a new creation. And the highway stretches ever so long in between them.