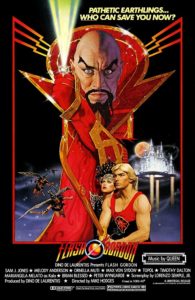

“Pathetic earthlings. Hurling your bodies out into the void, without the slightest inkling of who or what is out here. If you had known anything about the true nature of the universe, anything at all, you would have hidden from it in terror.” – The Emperor Ming

There is a vague recollection in the back of my mind of walking in on 1980’s Flash Gordon while it was being played on TNT or TBS—or some other station back when the internet was still in its infancy—but I only recall the blonde-haired, blue-eyed savior of the universe and what I considered to be pretty low production value even at my young age. Nothing else. Outside of that one memory, I don’t recall ever actually watching Flash Gordon. So when my local independent theater, Circle Cinema, had a late showing of it on its 40th anniversary, I figured there was no better way to experience a film for the first time than on the big screen.

There is a vague recollection in the back of my mind of walking in on 1980’s Flash Gordon while it was being played on TNT or TBS—or some other station back when the internet was still in its infancy—but I only recall the blonde-haired, blue-eyed savior of the universe and what I considered to be pretty low production value even at my young age. Nothing else. Outside of that one memory, I don’t recall ever actually watching Flash Gordon. So when my local independent theater, Circle Cinema, had a late showing of it on its 40th anniversary, I figured there was no better way to experience a film for the first time than on the big screen.

Folks, I’m here to tell you, this film works on every level. Sure, it’s not flashy and seamless with its effects and Sam Jones—“Quarterback for the New York Jets!”—is far from most engaging actor, but what it does have is something that is often missing from superhero movies today: joy. Every single scene emits this ferocious love of this odd little film by those making it. It’s not as if this is a bunch of no names making a DIY indie feature. The film features Max von Sydow as The Emperor Ming—there is probably much that could be said about this character in a cultural analysis, but I’ll save that rant for another time—Brian Blessed as Prince Vultan, Timothy Dalton as Prince Barin, and Topol (of Fiddler on the Roof fame!) as Dr. Hans Zarkov. All of the actors buy into their roles and look like they are having a wonderful time in the process. Not to mention a soundtrack by one of the all-time great rock and roll bands, Queen, and helmed by Mike Hodges, the director of one of the all-time great grimy, British angry young man films, Get Carter. The film is bursting forth with talent in front and behind the camera.

There is an element of this production that reminds me of the Safdie Brothers’ approach to making films: having veteran actors play off of people with little to no acting experience. They have done this in all of their films and while the Safdies have this element down to a seamless art, there is a seed of this brilliance in Flash Gordon as we see Sam J. Jones’ naiveté up against some superb veteran actors. It works. It helps everyone buy into the process and, for my own enjoyment, draws a direct line from Mike Hodges to the Safdie Brothers.

And this is the thing, this is the kind of film that rouses the audience into joyful abandon. People in my screening were singing along with the opening Queen track, laughing at all of the lines that are not good, but are so memorable as to be engrained in our cultural subconscious. People can say what they want about cult classics, but in defining what is cinema, these films can and should compete with the Scorseses, Coppolas, Cassavetes, etc. for the hearts of filmgoers. After all, that which traverses from the projector to the screen to our eyes down to our hearts is sacred. It changes us mostly for the better. Serious cinema incorporates joy as well as drama. My countenance was lifted into a stupid grin after Flash and Dale head back to New York after saving the world in 14 hours(!), something that rarely happens in Marvel and DC films now.

And this is the thing, this is the kind of film that rouses the audience into joyful abandon. People in my screening were singing along with the opening Queen track, laughing at all of the lines that are not good, but are so memorable as to be engrained in our cultural subconscious. People can say what they want about cult classics, but in defining what is cinema, these films can and should compete with the Scorseses, Coppolas, Cassavetes, etc. for the hearts of filmgoers. After all, that which traverses from the projector to the screen to our eyes down to our hearts is sacred. It changes us mostly for the better. Serious cinema incorporates joy as well as drama. My countenance was lifted into a stupid grin after Flash and Dale head back to New York after saving the world in 14 hours(!), something that rarely happens in Marvel and DC films now.

Along with my utter enjoyment of the film, I couldn’t help but zero in on an element in the earlier moments of the film. After Zarkov has forced Flash and Dale into his spaceship at gunpoint and they have arrived on the planet, Mongo. They are walking through the grand halls of Ming’s palace and his enforcers are lined up along the walls on both sides. Flash, this seemingly dumb jock, notates that this world looks like a police state and Zarkov responds back to him by saying that these henchmen are just waiting for a leader to rise up and lead them in revolt against their oppressor. Right there in this midst of this grand space opera is a Marxist analysis of class warfare. They are waiting for their Moses to free them from the slavery of their Pharoah.

This elements of class and communal concern seldom find their way into modern genre films because American society is so subsumed by its individualist narrative of history, ethics, religion, society, and politic that how communities filter into the program becomes almost negligible. This is part of the reason why America has continued the story of the “middle class nation” while the rich only get richer and the poor, poorer. Most superhero movies today are too obsessed with power—“with great power comes…,” well, you know the rest—instead of how people relate on micro and macro levels. Flash Gordon, meanwhile, is just a lowly quarterback (ha!) and has no supernatural power only throwing arm and chutzpah. He is willing to sacrifice himself—for he is totally human—for the good of the world, freeing the captives on Mongo as well as those impudent earthlings. He is the hero we need, not the one we deserve.

Now, if these films had continued on, my argument above would have more than likely been diminished, because Flash Gordon is still based on a comic book character, one that profits off of survival only to return in the next issue. However, if we look at this film as a singular entity, it emits a giant shadow and it’s easy to see the ideas undergirding it compared to most American superhero films. I would love nothing more for the modern superhero genre to take a note out of the Flash Gordon playbook: let go of the special effects so that ideas—outside of how power embodies itself in society—can live and breathe in their stories and be just as memorable as that opening riff and line from Freddy Mercury: “FLASH! AaaaaHHAAAAAA SAVIOR OF THE UNIVERSE!!”