Imagine for a second: an amorphous mass of gelatinous ooze engulfs a person and, just as they open their mouth to air their protests of fear, the pulsating form reaches out its bulbous tentacle and begins to slide down the person’s esophagus, every empty space filled and expanded. If it was not bad enough that this person was drowning by way of solid matter, then the following work of dissolving—both inside out and outside in, simultaneously—makes the scene reach into the realms inhuman, unknowable terror.

Imagine for a second: an amorphous mass of gelatinous ooze engulfs a person and, just as they open their mouth to air their protests of fear, the pulsating form reaches out its bulbous tentacle and begins to slide down the person’s esophagus, every empty space filled and expanded. If it was not bad enough that this person was drowning by way of solid matter, then the following work of dissolving—both inside out and outside in, simultaneously—makes the scene reach into the realms inhuman, unknowable terror.

Eugene Thacker has a trilogy of books that look at the “Horror of Philosophy” and quite often uses Lovecraft and other “cosmic horror” writers to underpin his conception of a fear as that which is not founded in the minds of humanity. It is neither anthropomorphism—attributing human characteristics to things or beings that are not human—nor anthropocentrism—wherein human beings become the most central being of the universe—but it is a fear of entities or presences that humanity has no categories for, no definitions laid down, it is wholly other and, therefore, is inhuman and unwilling to be humanized. It is “universal absence” according to the philosopher, Emmanuel Levinas; it is indifference. And entities that consume us without taking any notice of us is perhaps the greatest human fear.

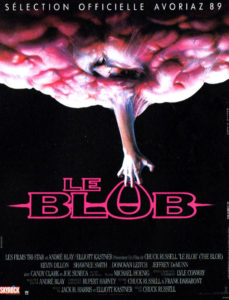

Enter The Blob. In the three films focusing on this meteoric space jelly—1958, 1972, and 1988—we see an amorphous, pulsating, gelatinous mass fall to Earth (Where from? We don’t know.) and begin to devour everyone and everything in its path (Why? We don’t know) and, as it consumes, it grows. It does not care about gender, race, creed, age, or any other biological category or social construct we place on each other, it just devours and absorbs us into its being. It is wholly other. It has no face with which to read emotions. It has no mouth in order to communicate thoughts. Its shape defies any consistent description or anthropomorphism we could place on it. It shifts like a cloud; a growing, malignant mass bent on devouring until there is nothing left except its own existence.

With a good portion of horror, there is a sense that the villain or creature kills for a purpose, that it takes notice of humanity and chooses to kill us. Not so with the creatures that bleed out from the dark void. They are indifferent to what, who, or why we are. Their ways are not even remotely our ways. They are inhabitants of what Thacker calls the Planet, or “the world-without-us.” They are the antithesis of the Divine will of the Christian God and yet they share in one central characteristic: they are both wholly Other and set apart from humanity.

One of the key characteristics of Christian thought is the distinction between God and creature. The Trinitarian person of the Father is spirit and is not human and cannot be known outside of its self-revelation. In a similar way, the blob is amorphous being that is unlike anything humanity has seen in their existence. There is a separateness between the blob and humanity, that is until the blob discloses itself to humanity in all of its abject horror.

One of the key characteristics of Christian thought is the distinction between God and creature. The Trinitarian person of the Father is spirit and is not human and cannot be known outside of its self-revelation. In a similar way, the blob is amorphous being that is unlike anything humanity has seen in their existence. There is a separateness between the blob and humanity, that is until the blob discloses itself to humanity in all of its abject horror.

Within the course of each of these films, the townspeople struggle to comprehend what, in fact, is actually happening and what, in fact, this entity that devours without any seeming purpose or notice of our importance is. Whenever they find that the blob does not like being cold and could be temporarily stopped by being frozen, the revelation comes as mere chance; a happy stroke of luck. The blob has no interest in expressing itself fully and allowing the town’s inhabitants to comprehend its being. It just goes about its perpetual path acting according to its will with constituent apathy.

The people unfortunate enough to cross its path find themselves peering into the dark void of being, a type of nothingness, pure deprivation. Some, against their will, become part of its being, it’s nihility, physically as they are liquefied within the mass. Others like Reverend Meeker in the 1988 version, peer into the void and embrace its existence and the nothingness that follows in its wake. Reverend Meeker sees the blob as damnation incarnate. He declares to his revival congregants at the end of the film:

“Consuming sinner and saint alike… who shall be lifted up to rapture when the judgment trumpet blows? None but the faithful, brothers and sisters… none but the faithful.”

He places his faith in the impersonal judgment of fate, mere cold chance, much like The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or Chigurth in No Country for Old Men. Judgment happens arbitrarily. The whims of the unknown and unmerciful.

He places his faith in the impersonal judgment of fate, mere cold chance, much like The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or Chigurth in No Country for Old Men. Judgment happens arbitrarily. The whims of the unknown and unmerciful.

There is a stark difference between the blob’s indifferent otherness and the otherness displayed by the Christian God. The fact that God’s priest, Reverend Meeker, gives in to the void and deprivation states more about his humanity than about the God of which he is supposed to be representative. God reveals Himself in the form that humanity most relates to, which is ourselves. His being is personal and intimate and His judgment is tied up in His love and concern for His creatures. He is not a force of fate, nor a deprivation or void. Instead He is fullness of being and life and He seeks to open eyes to His goodness and nature.

He, too, seeks for us to be a part of His being. As the apostle said, “it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” His being is imparted to us, unambiguously and non-arbitrarily, instead of us being absorbed into His being. The holy Father sets the proper context for anthropocentrism, we are infinitely important because we are His creation, made in His image, carrying the full weight of His glory. We can anthropomorphize God because He has a physical face in Jesus Christ. His revelation gave us the human face of the divine. We can relate to God because He became man.

It’s almost poetic when one contemplates the nature of the blob over and against the nature of the Christian God. One shows itself and is without shape, without connection, and judgment without love or care. It moves along with pulsating deprivation and coldness. The latter, while wholly other and separate, shows His face. His Son has defined shape—body, mind, emotion, blood—and is intentional in His connection. His judgment is founded in love and intimacy. Chance has no place in the pulsating rhythms of His existence.

Where H.P. Lovecraft and his cosmic horror compatriots came up against a wall with their cosmic pessimism is their lack of answer to the void they so profoundly and deftly describe. The blob is one of the incarnations of this void in horror canon. We can’t explain it. We can only struggle with it and perhaps happen upon the temporary mechanism to slow its advance. We can’t stop it. However, there is something behind the void that tears that curtain of darkness apart so that man can see and understand. Be thankful that the faith affirms a God who lovingly chooses to reveal Himself to us instead of slithering along with the suffocating abyss held within it.

Where H.P. Lovecraft and his cosmic horror compatriots came up against a wall with their cosmic pessimism is their lack of answer to the void they so profoundly and deftly describe. The blob is one of the incarnations of this void in horror canon. We can’t explain it. We can only struggle with it and perhaps happen upon the temporary mechanism to slow its advance. We can’t stop it. However, there is something behind the void that tears that curtain of darkness apart so that man can see and understand. Be thankful that the faith affirms a God who lovingly chooses to reveal Himself to us instead of slithering along with the suffocating abyss held within it.