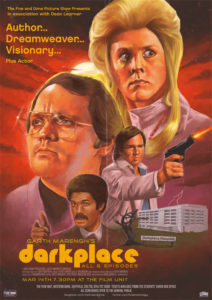

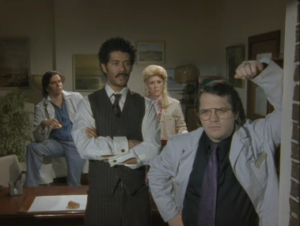

The second episode of Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace finds its comedic locus in the obliviousness to the privilege that men have in society. Liz (played by the superb Alice Lowe) came to Darkplace as a new hire straight out of “Harvard College Yale” having “aced every semester, and [gotten] an ‘A’” in episode one. Even with such highly esteemed credentials, episode two shows us that even in the strange environs of Darkplace, Liz finds herself being held as a second class citizen and piece of meat for the male gaze. Dagless, Reed, and Sanchez treat her as nothing more than a glorified secretary.

The second episode of Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace finds its comedic locus in the obliviousness to the privilege that men have in society. Liz (played by the superb Alice Lowe) came to Darkplace as a new hire straight out of “Harvard College Yale” having “aced every semester, and [gotten] an ‘A’” in episode one. Even with such highly esteemed credentials, episode two shows us that even in the strange environs of Darkplace, Liz finds herself being held as a second class citizen and piece of meat for the male gaze. Dagless, Reed, and Sanchez treat her as nothing more than a glorified secretary.

Then there is the chicken incident in episode two. Doctors and staff stand in line in the hospital cafeteria while they wait, with growing impatience, for the cook to finish the chicken that will be their lunch. Complaints coming from everyone in line get expressed by Liz when she declares, “Where’s the flippin’ chicken!?” All the complaints fall on the deaf ears of the cook until a woman dared to complain. The cook responds, angrily, “Women like you are the reason this chicken’s late in the first place. You’ll be lucky if you get any of my lovely chicken if you keep up this kind of behavior.” Never mind the potential metaphorical reading of that exchange between a man and a woman with a piece of meat at its focus, the exchange is pinpointing something that is ignored in a patriarchal system: women’s inability to air critiques, complaints, or resist without personal attacks and degradation by men.

It’s not this incident only, but the commentary continues throughout as male character after male character asks her to do something that is beneath her status and value. Dean Learner asks her to “fish a bulb” out of his drawer and change the one that has gone out. They knock her food trays down over and over again. They treat her like a child led by emotion only as they buy into the stereotype of women as primarily emotional creatures and men as rational creatures. With each slight—as goofy and played for comedy as they each are—Liz becomes internally enraged by this treatment, a visual representation of what most women feel in everyday life as they are consistently and systemically treated as second-class citizens behind the “more valuable and rational and stronger” men. This rage turns into a telekinetic display throughout the hospital not unlike that shown by its more serious precursor, Carrie.

The most brilliant part of episode two’s commentary on patriarchal society is what items are shown to be floating around the hospital attacking the male figures once Liz’s powers are ignited. Domesticated items like ladles and forks, irons, trash cans, staplers, etc. become the weapons in which Liz telekinetically manipulates. Each of these being items that fall within traditional understandings of women’s work—cooking, cleaning, laundry, secretarial work etc. The only time a man is actually killed within the scope of the episode by these levitating items is when a tool tray of screwdrivers penetrates a young man who was just hired on to the hospital. However, even the choice of the tool, the “penetration” of the tool into the male body, and the fact that the young man was hired as a temp—a position often identified under “female work”—all play into the commentary of female rage against a system that treats them as mere bodies to be used by men and lesser in their value when it comes to influence and placement outside of male-defined domestic spheres.

The most brilliant part of episode two’s commentary on patriarchal society is what items are shown to be floating around the hospital attacking the male figures once Liz’s powers are ignited. Domesticated items like ladles and forks, irons, trash cans, staplers, etc. become the weapons in which Liz telekinetically manipulates. Each of these being items that fall within traditional understandings of women’s work—cooking, cleaning, laundry, secretarial work etc. The only time a man is actually killed within the scope of the episode by these levitating items is when a tool tray of screwdrivers penetrates a young man who was just hired on to the hospital. However, even the choice of the tool, the “penetration” of the tool into the male body, and the fact that the young man was hired as a temp—a position often identified under “female work”—all play into the commentary of female rage against a system that treats them as mere bodies to be used by men and lesser in their value when it comes to influence and placement outside of male-defined domestic spheres.

Rick Dagless (our show’s central protagonist), Lucien Sanchez and Thornton Reed are all oblivious to the actual reason for Liz’s rage in the first place. Dagless airs this in one of his voice-overs:

“We’d seen a new side to Liz. ‘Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.’ They can get upset at the slightest thing: whether it’s forgetting to acknowledge them in front of your friends or dividing a restaurant bill in proportion to the amount of food ordered by each party, which is only fair. I had to change. Tomorrow I’d tell her she’s lost weight or I like what she’s done to her hair. Whichever seemed the most plausible.”

Male comprehension of legitimate complaints and critiques of society by women finds its termination in minimizing the complaint/critique as “the slightest thing” while taking for granted the very privileges that allow men to not experience the oppression and devaluing that women go through on a day-to-day basis in reality. When Dagless is faced with a possessed and levitating Liz, his first concern is not her safety, not what brought her to that state in the first place, but, instead, the fact that he can see under her skirt for which her chides her, “Liz, hide your shame.” While men can objectify and gaze at women all day to satisfy their own sexual fantasies and appetites, women’s sexuality is brought to the level of shame.

What makes this satirical critique work so well is the note it chooses to end on. Dagless violently knocks her out of her possessed state by throwing a fire extinguisher at her head and then goes over to the dead temp and howls in grief at the loss of this throwaway minor character. If the temp had been a women, we can only assume that Dagless’ response would have been significantly different based on how Liz, who is a main character on the show, was treated throughout the episode. Once again, the men save the day and instead of changing their own behavior and addressing the critiques and complaints that led Liz to that space in the first place, they give her a lobotomy to “extract psycho-kinetic ability,” a procedure that is still “in its infancy, though surprisingly simple all the same.”

What makes this satirical critique work so well is the note it chooses to end on. Dagless violently knocks her out of her possessed state by throwing a fire extinguisher at her head and then goes over to the dead temp and howls in grief at the loss of this throwaway minor character. If the temp had been a women, we can only assume that Dagless’ response would have been significantly different based on how Liz, who is a main character on the show, was treated throughout the episode. Once again, the men save the day and instead of changing their own behavior and addressing the critiques and complaints that led Liz to that space in the first place, they give her a lobotomy to “extract psycho-kinetic ability,” a procedure that is still “in its infancy, though surprisingly simple all the same.”

The men stay oblivious, the women must change to better suit the comfort of men, and the absurdity of the whole scenario realistically parallels the actual issues inherent in a patriarchal system that still holds sway. When Liz apologizes at the end of the episode for her actions—for being “unprofessional and girlish”—the audience is meant to find that response absurd. That absurdity should be transposed onto reality, because underneath the exaggeration is a truth that gives the comedic elements a harder edge.

Who knew “being told [she] couldn’t get a chicken supper” would find its way into the acceptable allegorical realms of gender equality? Garth Marenghi did. Maybe. Probably not, actually.