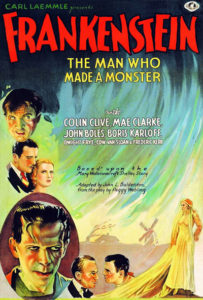

James Whale brought to the screen what is considered the most dynamic film in the first cycle of Universal monster pictures of the 1930s, 1931’s Frankenstein. Though diverging from Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, in three significant ways–making the monster silent, introducing Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant, Fritz, and the doctor’s religious confession of remorse towards the end–the film still trades on the same thematic concerns of the novel:

…humanity’s attempts to conquer mortality; the vexed relationship between man and God; the moral responsibility of science; the hapless creature as lonely, even existential outcast–are envisioned here in thoroughly cinematic ways (Rick Worland, The Horror Film: An Introduction, pg. 160).

Frankenstein in most of its incarnations has sought to explore the central consequences of ‘man playing God.’ Much critical attention has been paid to this ideological element especially by religious analysis, usually pegging the negative proponents of man’s attempt to do what only God could do: breathe life into inanimate beings. Within a Christian framework, man’s attempts at displacing God usually end in tragedy, leading to the inevitable destruction of the faux god in some way whether physically, existentially or some form of Faustian damnation.

Frankenstein in most of its incarnations has sought to explore the central consequences of ‘man playing God.’ Much critical attention has been paid to this ideological element especially by religious analysis, usually pegging the negative proponents of man’s attempt to do what only God could do: breathe life into inanimate beings. Within a Christian framework, man’s attempts at displacing God usually end in tragedy, leading to the inevitable destruction of the faux god in some way whether physically, existentially or some form of Faustian damnation.

But what exactly is it about this conceit of Dr. Frankenstein’s ‘creation’ that really transgresses the chasm between the holy and the earthly? While it is true that in traditional Christian theology God created out of nothing by mysterious and utterly powerful speech acts–God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light (Gen. 1:3 NKJV), I am not convinced that it was merely the drive of Dr. Frankenstein to create life that transgressed the God/created being divide. Genesis 1:28 speaks prominently of what has been titled “the cultural mandate” of Christians:

Then God blessed them [man and woman], and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.

Now, the language of the ancient Hebrews here has been misunderstood and misused in various ways, but that’s another discussion. I just want to point out how this verse gives humanity the ability and power to create. Procreation is a means of bringing a person with life into the world. This is praised in the Bible as a good and intimate thing. It is something that echoes Dr. Frankenstein’s desire to bring life into the world. Yes, how he goes about doing it is distorted and problematic, but I want to maintain that the desire to bring something to life is not necessarily bad, but is a desire that has been instilled in us from the beginning. Creation is a good gift of God to his creatures, everything created by us is, in some way, bringing ‘life’ into the world, even though our creation is not from nothing like God’s according to Christian theology.

So what is it about Dr. Frankenstein’s actions that becomes a type of allegorical blasphemy of the perfect, comprehensive goodness of God’s creative acts in the first two chapters of Genesis? Rick Worland’s essay, “Frankenstein (1931) and Hollywood Expressionism,” in his book, The Horror Film: An Introduction, happens upon the problem even though theological concerns are not his aim in the essay. Worland recounts the scene after the monster’s creation–an utterly iconic scene in Hollywood history–where the monster is alive and speechlessly implores his creator:

As the light falls on its face, he looks up hesitantly, a subtly beautiful expression of innocence and longing crossing the grotesque visage, He rises and stretches his arms toward the ethereal substance that gave him life, seeking to clasp it in his hands. When Henry removes the light the monster sadly repeats the pathetic gestures toward the only “parent” left, Dr. Frankenstein, who simply orders it to sit once more. Oblivious to his creature’s emotional pain, Henry marvels, “It understands this time. It’s wonderful!” This moment of pathos and misapprehension is destroyed by Fritz’s frenzied call of “Frankenstein! Frankenstein! Where is it?,” as the hunchback races in with a torch, sadistically thrusting it into the creature’s face. Fritz’s torment of the creature is apparently ongoing. Why Frankenstein permits it is not clear, but can be taken as evidence of his almost immediate neglect of the living thing he boasted of forming with his own hands (pg. 169).

It’s in Dr. Frankenstein’s immediate neglect of his created being I think lies the central moment in which blasphemy happens. Dr. Frankenstein’s modus operandi for creating “the monster” was ultimately a matter of pride and selfishness. He did not ultimately care about the thing he created, but instead sought to boast of his scientific prowess. If one contrasts this with the narrative told in the second chapter of Genesis from verses 8-25, we see something quite opposite from this neglect and selfishness. God creates the world, the garden, and places Adam in it, gives him woman because “It is not good that man should be alone,” and God has relationship with his creation.

It’s in Dr. Frankenstein’s immediate neglect of his created being I think lies the central moment in which blasphemy happens. Dr. Frankenstein’s modus operandi for creating “the monster” was ultimately a matter of pride and selfishness. He did not ultimately care about the thing he created, but instead sought to boast of his scientific prowess. If one contrasts this with the narrative told in the second chapter of Genesis from verses 8-25, we see something quite opposite from this neglect and selfishness. God creates the world, the garden, and places Adam in it, gives him woman because “It is not good that man should be alone,” and God has relationship with his creation.

Within the narrative of Genesis, God does not neglect his creation. Sure, He lays a curse on it, he punishes them, but that is not neglect. There is care inherent in these actions. Dr. Frankenstein is ultimately indifferent to that which he gave life to which is where the real problem underneath “man playing God” comes: what humanity creates is ultimately out of selfishness. God’s creation of humanity was an act of the outpouring his image, breathing existence into nonexistence. It is utterly selfless. He created us as good and related to us, walked in the garden with us. Knew us, loved us, poured Himself into us. Dr. Frankenstein created life, but the direction of his love was at himself alone, not being attentive to the physical and emotional pain of his creation, showing indifference to the “monster.”

Though the monster’s plea to the doctor for a mate is ignored in the 1931 film, it is a significant moment in the original novel. Dr. Frankenstein does give into the pleas of the monster and begins making the monster’s mate, but then decides against it and starts shredding the body, leading the monster to vow “revenge in kind on his maker, promising: ‘I shall be with you on your wedding night'” (pg. 171). Once again we see the doctor’s unwillingness to be in relationship with, to actually take responsibility in caring for, the being he created. Indifference is the most inhuman trait one could show toward another person, toward one’s creation. Nothing in the entire testimony of the Scriptures could peg God as indifferent to that which He created. Period.

Here Frankenstein makes his tragic error. In sorrow and disappointment, he abandons the creature rather than take responsibility of it…but [Frankenstein] will not acknowledge the Monster’s grunts of physical pain any more than he recognized it emotional yearning.

Unlike the doctor, God takes full responsibility for a creation he made and ultimately rebelled against him–beginning a systemic and enduring brokenness that affected all aspects of creation and humanity according to Christian tradition. Where Dr. Frankenstein in the film states “I made him with these hands and with these hands I will destroy him,” God, instead, “destroys” Himself by placing his Son on the cross. Selfless.

Unlike the doctor, God takes full responsibility for a creation he made and ultimately rebelled against him–beginning a systemic and enduring brokenness that affected all aspects of creation and humanity according to Christian tradition. Where Dr. Frankenstein in the film states “I made him with these hands and with these hands I will destroy him,” God, instead, “destroys” Himself by placing his Son on the cross. Selfless.

It’s no accident that the prologue of the Universal Frankenstein film frames the story with an echo of the original Genesis creation story: Frankenstein “sought to create a man after his own image.” It is interesting then that God’s creation of man is good–until the creation turns against their Creator–and man’s creation of man is a “monster,” though not because of the monster, but because of his creator’s selfishness thereby inverting the Judeo-Christian creation story. James Whale’s Frankenstein, along with Shelley’s novel, shows us that “man playing God” is bad because an inevitably selfish man displacing a selfless God is monstrosity.