Richard Matheson is a name few people probably know—outside of horror and science fiction fanatics—but he has written stories that have received many film and television adaptations throughout the years, not to mention writing the screenplays for many of them. From the classic Twilight Zone episode, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” with William Shatner to the more recent adaptation of The Box by Richard Kelly (Donnie Darko), Matheson’s imprint is all over the horror genre. However, none of the adaptations come close to the popularity and enduring mythology of his novella, I Am Legend, which has been adapted into four films, a comic series and a radio play from BBC.

Richard Matheson is a name few people probably know—outside of horror and science fiction fanatics—but he has written stories that have received many film and television adaptations throughout the years, not to mention writing the screenplays for many of them. From the classic Twilight Zone episode, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” with William Shatner to the more recent adaptation of The Box by Richard Kelly (Donnie Darko), Matheson’s imprint is all over the horror genre. However, none of the adaptations come close to the popularity and enduring mythology of his novella, I Am Legend, which has been adapted into four films, a comic series and a radio play from BBC.

The original story Matheson told was a post-apocalyptic tale of a man who survives a ravaging disease that turns its victims into zombie-like vampires that come out at night seeking the blood of the living. Robert Neville is the last man on earth—so it seems—and finds himself living a lonely existence amid those who have already turned. He finds himself researching the potential causes for the disease and finds more efficient means of killing the infected. The story ends with Neville being betrayed by a member of a new race of humanity born out of the pandemic. By the end of the book, he comes to realize that he, the last human on earth, has become a monster to the new race. His end triggers the beginning of the mythos, or legend, around “humanity.”

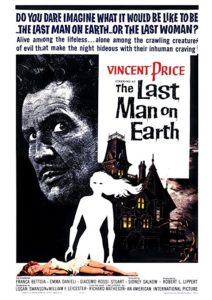

Each of the film adaptations bring various inflections on the story and commentary. There are elements of each film that I appreciate, but it is the original 1964 version, The Last Man on Earth, starring Vincent Price that continues to capture my mind and imagination the most and, yet, it is the least action-packed adaptation of the story. Some have even critiqued it as dull and poorly pieced together. Though rather raw in some places, I do not see this criticism as being something that weakens the power of the film.

Richard Matheson wrote the screenplay for the 1964 version, but ended up not liking the way the film was shaping up under directors Ubaldo Ragona and Sydney Salkow, so he was credited under the name Logan Swanson. Even though Matheson was not pleased with the final product, the film strikes many intriguing thematic notes, not just those brought up in the novella itself. Where The Last Man on Earth improved on the narrative of the novella was in allowing the protagonist to find a cure for the vampiric germ right before he is killed by the hands of those infected. Singlehandedly, the film’s narrative transcends the original’s social commentary and reaches for thematic heights that could only be described as sacramental. The seeming futility of the film is that the infected destroy the very man that could cure them.

Richard Matheson wrote the screenplay for the 1964 version, but ended up not liking the way the film was shaping up under directors Ubaldo Ragona and Sydney Salkow, so he was credited under the name Logan Swanson. Even though Matheson was not pleased with the final product, the film strikes many intriguing thematic notes, not just those brought up in the novella itself. Where The Last Man on Earth improved on the narrative of the novella was in allowing the protagonist to find a cure for the vampiric germ right before he is killed by the hands of those infected. Singlehandedly, the film’s narrative transcends the original’s social commentary and reaches for thematic heights that could only be described as sacramental. The seeming futility of the film is that the infected destroy the very man that could cure them.

“Then Jesus said to them, ‘Most assuredly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, you have no life in you.’” – John 6:53 (NKJV)

The imagery is, perhaps, a little on the nose in its Christocentric parallels. The one man’s body whose blood provides the antibodies that would reverse the living death of those infected is pierced by a spear on the altar of a church, sprawled out like Christ. A savior murdered unjustly. A declaration is made about the knowledge and wills of those who did the killing: “they didn’t know.” And, yet, Ruth—a member of the new race who was cured of her vampirism by Morgan—becomes the disciple and the carrier of the cure within her very body.

If we were to take this analogy to its conclusion within the scope of the film, Ruth had been washed clean and brought back to the living by the blood of Morgan, a “type of Christ”—simplifying a technical theological concept. Morgan has been killed by the very people who needed him, who needed his blood unto salvation. Yet they preferred to make their way and progress their new race by their own means, replacing the cure for something that largely addressed the symptoms and not the disease. Ruth, then, becomes the quintessential apostle of the mythos of Robert Morgan, the final human who ever lived. She walks by one of the females (with child) of the new race and declares that everything will be okay now because she understands and is the beneficiary of his blood. It is a declaration that brands the whole book of Acts amidst severe opposition shown to Christ’s disciples.

Vampires and zombies—both of which have been represented in the various adaptations of I Am Legend—are sacramental monsters. They require the body and blood of one who lives. They feed off it and are in continual dependence on it. They must partake in it consistently. The imagery of these creatures in The Last Man on Earth—and every other story surrounding them— is one that takes a more Catholic understanding of body and blood (transubstantiation: the actual conversion of the elements into the body and blood of Christ). However, one does not have to be Catholic to allow the film’s sacramental overtones to achieve a symbolic meaning that patterns itself after a salvation wrought by the actual, literal body and blood of Christ.

Vampires and zombies—both of which have been represented in the various adaptations of I Am Legend—are sacramental monsters. They require the body and blood of one who lives. They feed off it and are in continual dependence on it. They must partake in it consistently. The imagery of these creatures in The Last Man on Earth—and every other story surrounding them— is one that takes a more Catholic understanding of body and blood (transubstantiation: the actual conversion of the elements into the body and blood of Christ). However, one does not have to be Catholic to allow the film’s sacramental overtones to achieve a symbolic meaning that patterns itself after a salvation wrought by the actual, literal body and blood of Christ.

The film then transcends the source material and turns it on its head. It stops being merely social commentary about the distortions of human perception about the “other” and becomes a reflection of the greatest injustice the world has seen towards the one who truly was other (both God and man) and innocent. And, yet, out of injustice came unwarranted justice and grace towards those who needed him.

Humanity keenly finds itself on the side of shedding blood instead of drinking and being cleansed by it. Just like the new race in The Last Man on Earth, they prefer their own solution which amounts to nothing more than a whitewashed tomb rather than seeking the very person who could, once again, give them life back and banish the disease from existence.

It’s in the film’s final moments that we get echoes of Golgotha as Vincent Price collapses with spear in side while recognizing the distorted nature of those who have wounded and killed him and yet succumbing to death. It’s an imagery that speaks to our very souls, a reality, fractured. We, humans, always seek to destroy the cure, because we can’t stand to receive something that did not come from our own hands. And, yet, when the blood has run down the steps of the stone altar of the church and begun to soak into the ground, a hope remains. Those who have ears to hear, eyes to see and veins that receive new blood will become the vessels and catalyst for spreading the cure for living death.

It’s in the film’s final moments that we get echoes of Golgotha as Vincent Price collapses with spear in side while recognizing the distorted nature of those who have wounded and killed him and yet succumbing to death. It’s an imagery that speaks to our very souls, a reality, fractured. We, humans, always seek to destroy the cure, because we can’t stand to receive something that did not come from our own hands. And, yet, when the blood has run down the steps of the stone altar of the church and begun to soak into the ground, a hope remains. Those who have ears to hear, eyes to see and veins that receive new blood will become the vessels and catalyst for spreading the cure for living death.