Despite their Stephen King pedigrees and the guiding hand of writer-director Frank Darabont, few films initially appear to have as little in common as The Shawshank Redemption and The Mist.

Despite their Stephen King pedigrees and the guiding hand of writer-director Frank Darabont, few films initially appear to have as little in common as The Shawshank Redemption and The Mist.

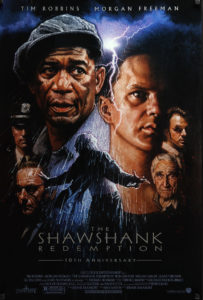

Released in 1994 to critical acclaim but little fanfare, Shawshank found a devoted audience through repeat cable airings, quickly becoming a mainstay atop IMDb’s list of great films. It is a tale of friendship and endurance, hung on the dependable frame of a prison escape narrative. For a certain generation, it’s a spiritual experience.

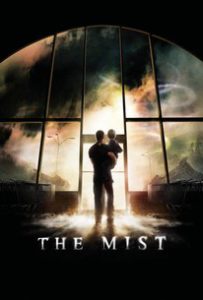

Thirteen years later, following another King adaptation (The Green Mile) and the Capra-esque misstep, The Majestic, Darabont returned to the author’s work once again. Where Shawshank was a tale of uplift, The Mist was angry and cynical. On the surface, it’s a creature feature complete with creepy crawlies and a healthy dose of gore. But it is not “fun” horror; created in the wake of 9/11 and the “War on Terror”, Darabont found himself in a “mean mood,” eager to explore the darkest corners of humanity.

Aesthetically, the two couldn’t be more different. Shawshank is told in a classical style with sweeping crane shots, deliberate pacing, and narration by Morgan Freeman that lends warmth and depth to the script’s platitudes. The Mist–filmed with a crew Darabont worked with on the TV series, The Shield–is a muscular thriller captured with hand-held cameras. There’s no reassuring narration and no opera music to distract us. There’s just the mist, monsters, and despair.

Yet, a deeper look reveals that both stories are flip sides of the same coin. Both ask what happens to humanity in dark times and what role hope plays in that struggle.

Prison, Refuge or Both?

Both movies are, essentially, prison films. The Shawshank Redemption is, of course, literally one. It is centered on Red (Freeman), a convicted murderer resigned to spend the rest of his days behind the concrete walls of the imposing Maine prison. His life, however, changes when Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), a banker convicted of murdering his wife, comes to Shawshank. Andy’s peaceful way and desire to hold on to his humanity — hanging up girlie posters, carving chess pieces, securing beer for his inmates — strikes the others as odd, but it also inspires some to find something for which to live.

Both movies are, essentially, prison films. The Shawshank Redemption is, of course, literally one. It is centered on Red (Freeman), a convicted murderer resigned to spend the rest of his days behind the concrete walls of the imposing Maine prison. His life, however, changes when Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), a banker convicted of murdering his wife, comes to Shawshank. Andy’s peaceful way and desire to hold on to his humanity — hanging up girlie posters, carving chess pieces, securing beer for his inmates — strikes the others as odd, but it also inspires some to find something for which to live.

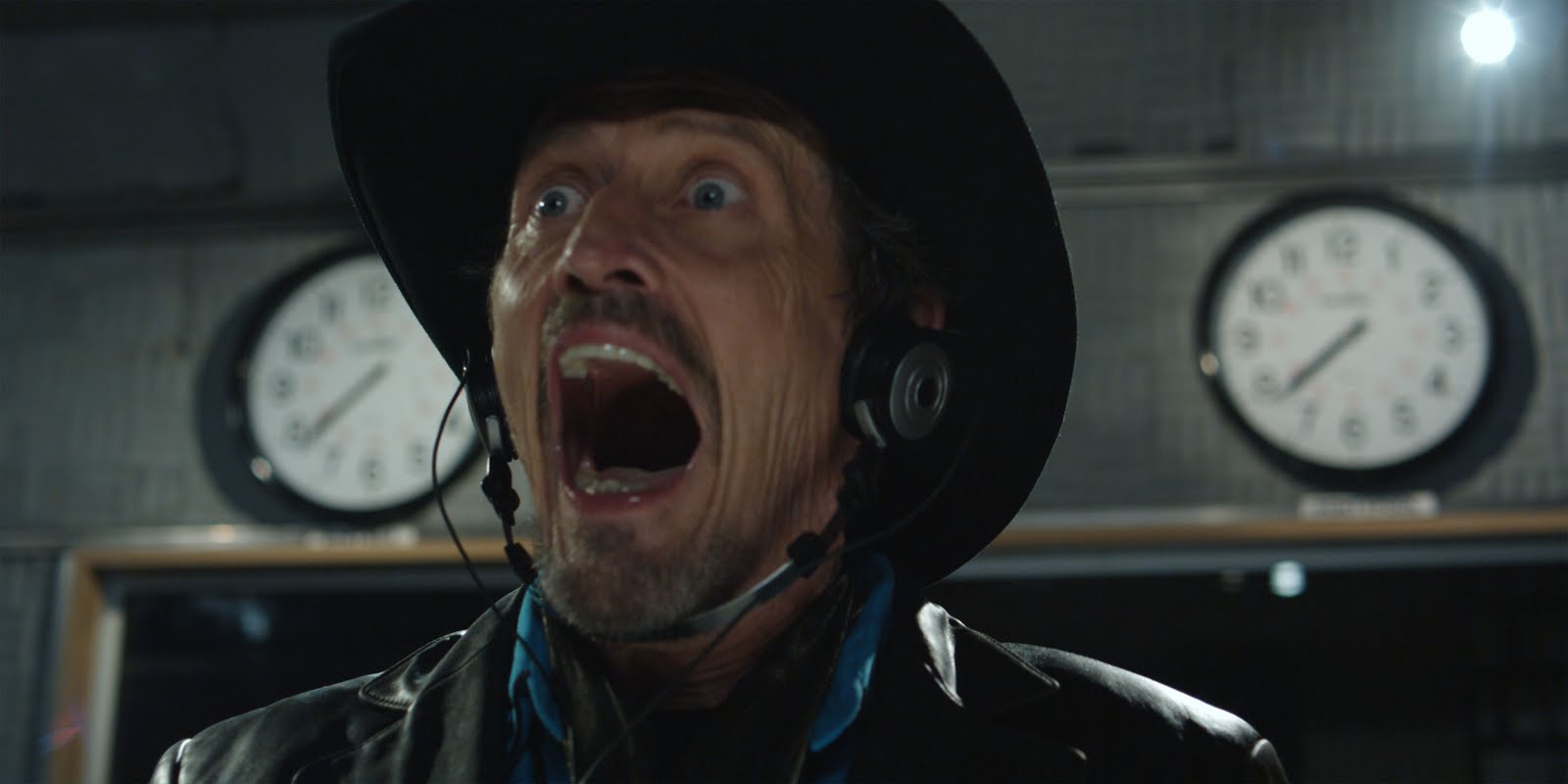

The Mist’s prison is one of choice, but it’s just as hard to leave. The film follows family man David Drayton (Thomas Jane), who takes his young son with him to the store after a storm knocks out the power and sends a tree through their picture window. While there, a strange mist covers the town, bringing with it vicious, Lovecraftian creatures. Amidst the deli counter, freezer section and bread rack, the townsfolk struggle to survive the horrors that emerge.

In both films, the difference between prison and refuge is turned on its head. The Mist’s townsfolk seek shelter only to see their sanctuary devolve into chaos. Trapped together, petty jealousies and prejudices arise. A loading dock worker (William Sadler) resents David’s warnings because he perceives that David is mocking his blue-collar mentality. An out-of-town lawyer (Andre Braugher) makes decisions seemingly based on rationality, but it is also a defense mechanism against town people who will never accept an outsider. Meanwhile, religious fanatic Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden) believes the mist and its monsters are God’s vengeance upon the residents of the town. Her every line oozes self-righteous priggery. With The Mist, Darabont looks at a world falling apart and fears that when the going gets rough, humans won’t stand together.

“As a species we’re fundamentally insane,” says one character. “Put more than two of us in a room, we pick sides and start dreaming up reasons to kill one another. Why do you think we invented politics and religion?”

The concrete walls of Shawshank aren’t exactly a sanctuary. Inside, the prisoners endure sadistic guards, sexual abuse, and a hellfire-spouting warden. Yet, for many, it’s home. The daily routine has ground them to a nub. They’ve found roles in the prison — James Whitmore’s elderly Brooks is the librarian and Red is Shawshank’s smuggler. The prison has been their punishment, but it’s also insulation from an outside world that has progressed without them and no longer needs them. When we view Brooks at work at a local grocer—perhaps, in King’s universe, the same one that eventually becomes a refuge for those caught in the mist—a customer complains that the old man previously forgot to double bag her groceries. She doesn’t understand that Brooks was away from grocery stores and public spaces for most of his life, just as the manager who later oversees Red upon release can’t understand why this former convict always asks permission to use the bathroom. There’s a division that exists between these “free” men and those who take their freedom for granted, a mindset that can never be shared.

The concrete walls of Shawshank aren’t exactly a sanctuary. Inside, the prisoners endure sadistic guards, sexual abuse, and a hellfire-spouting warden. Yet, for many, it’s home. The daily routine has ground them to a nub. They’ve found roles in the prison — James Whitmore’s elderly Brooks is the librarian and Red is Shawshank’s smuggler. The prison has been their punishment, but it’s also insulation from an outside world that has progressed without them and no longer needs them. When we view Brooks at work at a local grocer—perhaps, in King’s universe, the same one that eventually becomes a refuge for those caught in the mist—a customer complains that the old man previously forgot to double bag her groceries. She doesn’t understand that Brooks was away from grocery stores and public spaces for most of his life, just as the manager who later oversees Red upon release can’t understand why this former convict always asks permission to use the bathroom. There’s a division that exists between these “free” men and those who take their freedom for granted, a mindset that can never be shared.

The Shawshank prisoners have been “institutionalized.” Red is afraid he wouldn’t survive parole. He has shut out any hope of life outside Shawshank’s walls, and with good reason: In one of the film’s most devastating passages, we watch as a paroled Brooks tries to acclimate, only to take his life when he realizes there’s no place for him.

“They send you here for life, and that’s the thing they take away,” Red says. “The part that matters, anyway.”

How do we live together in hardship? Do we fall apart, stick to our routine, or can we find another way? Those are the questions Darabont is interested in.

Crooked Shepherds and False Prophets

The religious will say that faith is how we survive in troubled times, but King’s works aren’t exactly kind toward organized religion. Shawshank’s Bible-thumping Warden Norton wields scripture as a way to lord power and control over the inmates. While Norton knows his Bible and even feigns some measure of kindness to Andy, he’s as crooked as any prisoner in Shawshank. He uses his talented banker to cook the booksand when Andy learns of evidence that can prove his innocence, the warden has the witness murdered. When Norton shoots himself in the film’s third act, blood splattered on a homespun Bible plaque serves as the final judgment on his hypocrisy.

The religious will say that faith is how we survive in troubled times, but King’s works aren’t exactly kind toward organized religion. Shawshank’s Bible-thumping Warden Norton wields scripture as a way to lord power and control over the inmates. While Norton knows his Bible and even feigns some measure of kindness to Andy, he’s as crooked as any prisoner in Shawshank. He uses his talented banker to cook the booksand when Andy learns of evidence that can prove his innocence, the warden has the witness murdered. When Norton shoots himself in the film’s third act, blood splattered on a homespun Bible plaque serves as the final judgment on his hypocrisy.

But Norton is Billy Graham next to Mrs. Carmody. Marcia Gay Harden spits venom with every self-righteous platitude and pious proclamation. From the way she storms through the grocery store complaining about the lines, you understand that Carmody believes she’s better than anyone else in town. It takes nothing more than an earthquake and the appearance of the mist for her to believe the end of days is nigh, and she’s whipped into an almost sexual frenzy as she cries for “expiation” to silence God’s wrath. A shot of her sitting comfortably in a lawn chair casually brandishing a knife is a fantastic translation of King’s mix of the macabre and the mundane.

And yet, does the hypocrisy of these religious folk necessarily mean they’re wrong? Norton is an obvious white-washed tomb, but Carmody’s doomsaying comes true. The town is literally covered in smoke and there are swarms of vicious locust-like creatures that appear just as she said; one even stops its attack on her, perhaps realizing one of the chosen. Could there be something to her rants? Is she perhaps just aligned with the wrong side — a herald not of a vengeful God but of the devil? Is there still a good creator in the midst of this horror? The film leaves that option open.

“I believe in God, too. I just don’t think he’s the bloodthirsty asshole you make him out to be,” a biker says to Carmody before venturing into the mist.

“I believe in God, too. I just don’t think he’s the bloodthirsty asshole you make him out to be,” a biker says to Carmody before venturing into the mist.

King’s dark stories often belie humanity and spirituality. Indeed, the title of The Shawshank Redemption speaks to change and soulfulness. Andy Dufresne is a blatant Christ figure, an innocent man serving an unjust sentence. He endures violence and cruelty in order to “save” his fellow prisoners. He teaches them to read and plays music to remind them of life outside their concrete walls. In the end, he leaves his “tomb” and beckons his friend to join him in paradise.

The Shawshank Redemption is a story of miraculous change and renewal, especially when you remember that the titular redemption isn’t Andy’s but Red’s. Andy inspires his friend to think beyond his circumstances and, upon his escape, leaves a trail for him to follow, implanting a yearning in the convict’s heart. The Shawshank Redemption is not a “Christian movie” but it is a deeply spiritual one, preaching the gospel of hope.

Hope Is a Good Thing

Hope, and its role in our survival, is the uniting theme of both films.

Shawshank is an unsubtle sermon on its importance. After playing an aria for the inmates, Andy talks about music’s transportive power and vitality in a place like Shawshank. Red brushes it off, but Andy is undeterred. Before escaping, he tells Red about the bucolic spot where he proposed to his wife and makes him promise to visit it if he is released. Red is ultimately paroled, and his promise to Andy helps him avoid Brooks’ fate.

Shawshank is an unsubtle sermon on its importance. After playing an aria for the inmates, Andy talks about music’s transportive power and vitality in a place like Shawshank. Red brushes it off, but Andy is undeterred. Before escaping, he tells Red about the bucolic spot where he proposed to his wife and makes him promise to visit it if he is released. Red is ultimately paroled, and his promise to Andy helps him avoid Brooks’ fate.

What Red finds is a tin buried under rocks containing cash and a letter from Andy, urging him to continue his trek to Mexico.

“Hope is a good thing…and no good thing ever dies,” Andy’s letter reads.

Red breaks his parole and heads off to find Andy, wistfully dreaming of the Pacific Ocean and a reunion with his friend. Despite his hellish punishment in Shawshank, he’s learned to think beyond his situation and dream of something better, even when reality says it’s out of reach. The last words of the film are, “I hope.”

“Hope” is also the final word in King’s novella “The Mist.” To many who have seen the film, that might feel ironic, as the film’s ending is often considered one of the bleakest in cinema history.

David escapes the chaos at the grocery store with his son, an elderly couple, and a friend. They head off, driving into a world that has completely changed. The town has been destroyed. A 100-foot-tall tentacled behemoth lumbers across empty freeways. Darabont underscores the devastation with the mournful “The Host of Seraphim.” The jarring, operatic vocals and  haunting chords dominate the soundtrack, lending an otherworldly sense of doom to David’s journey into this new world. This moment is the opposite of “Shawshank’s” own operatic interlude; where that could be seen as a taste of Heaven, this feels like it’s playing in Hell’s waiting room.

haunting chords dominate the soundtrack, lending an otherworldly sense of doom to David’s journey into this new world. This moment is the opposite of “Shawshank’s” own operatic interlude; where that could be seen as a taste of Heaven, this feels like it’s playing in Hell’s waiting room.

Soon, the car runs out of gas. David and his passengers see no other option. They have a gun with four bullets. David shoots his passengers and then, emotionally destroyed, climbs out of the car to await his fate. Seconds later, an Army motorcade rolls in. Had David held on just one more minute, help would have arrived. He sinks to his knees in despair and the credits roll.

It’s not just a kick in the stomach. It’s a kick followed by a punch while doubled over. When I saw this film upon release, it felt like the air was sucked out of the theater, and the audience didn’t move for several minutes. Rewatching it as a father of two, it’s almost unbearable. Horror movies often end on dark notes, but this is one of the few I’ve seen with an ending that actually horrifies. I sat in my seat wondering how the man who gave us such an uplift with The Shawshank Redemption could deliver an ending so nasty and mean.

But, of course, Darabont is doing the work of an artist, examining the same theme from different angles. The ending of both films boils down to one point: the importance of not losing hope. In Shawshank, we see the reward of holding on. In The Mist, we see the devastation of not enduring. Both films deal with the power of hope — one does it in a positive light, the other in a negative. They come to the same conclusion: Hope keeps us alive.

An interesting thing happened on rewatch: I found The Mist more compelling and resonant than The Shawshank Redemption. Darabont’s first feature is still a charmer, but it wears its platitudes on its sleeve and often risks feeling trite. Maybe it’s just age or the difficult times we live in, but The Mist felt truer as I view a world that often seems to be going crazy. But maybe there’s still something worth clinging to. Both movies reminded me that as bad as it can get, the worst thing I can do is give up hope. It’s a good thing. And, as Andy said, no good thing ever dies.

An interesting thing happened on rewatch: I found The Mist more compelling and resonant than The Shawshank Redemption. Darabont’s first feature is still a charmer, but it wears its platitudes on its sleeve and often risks feeling trite. Maybe it’s just age or the difficult times we live in, but The Mist felt truer as I view a world that often seems to be going crazy. But maybe there’s still something worth clinging to. Both movies reminded me that as bad as it can get, the worst thing I can do is give up hope. It’s a good thing. And, as Andy said, no good thing ever dies.

Chris Williams has been a film lover since age 2 and a Stephen King fan since reading “It” as a middle schooler. He writes the “Mere Chris-ianity” blog at Patheos and has been writing about film and faith since 2005. His work has appeared in the Source Newspapers, The Grosse Pointe News, and at Christ and Pop Culture. Chris lives in the Detroit area with his wife and two kids.

The Shawshank Redemption (1994) & The Mist (2007)