Sorry To Bother You stands as one of those experiences that is so removed from expectations that it is hard to know how to feel about it after it has happened to you. It is not a film that one watches with analytical detachment, but a film that demands the viewer’s engagement. mother! was the last film to achieve this level of disorientation. This reviewer still has not come down on a side as to whether it could be categorized as “good” or “bad,” but came to the conclusion that whatever my personal feelings about it end up being, it is important. I feel the same way about Sorry To Bother You.

Sorry To Bother You stands as one of those experiences that is so removed from expectations that it is hard to know how to feel about it after it has happened to you. It is not a film that one watches with analytical detachment, but a film that demands the viewer’s engagement. mother! was the last film to achieve this level of disorientation. This reviewer still has not come down on a side as to whether it could be categorized as “good” or “bad,” but came to the conclusion that whatever my personal feelings about it end up being, it is important. I feel the same way about Sorry To Bother You.

The film moves beyond strict genre labels by including black comedy, drama, science fiction, transcendentalism, social commentary, metanarrative, existential angst and ethical concern within its cinematic language. Boots Riley, member of the politically-charged hip hop collective, The Coup, knows the language of film enough to subvert and undercut the typical story threads that would provide a comfortable and safe film experience. This film, after its first third, is one severe left turn after another hence the disorientation mentioned earlier. The discomfort and inability to get a grasp on the narrative direction works in Riley’s favor to a great extent. Engagement is required in order for access this film, for any kind of meaning to be revealed by it.

The downside to this form of filmmaking is the high risk of being uneven throughout he the whole runtime. While Sorry To Bother You could never be described as “boring,” its first third, comparatively, could be considered such by the standards of the final two-thirds of the film. For being so wildly imaginative and Riley’s direction having such life infused within it, the set up for the film feels too straight, too familiar, to be part and parcel of the same vision. While it contains imagery that tries to reach those heights, it isn’t until the final hour that it seems Riley has bought into his own vision. Once he does, there is nothing for the viewer to do but sit back and allow it to happen.

As someone who appreciates social commentary done well, it is perhaps the film’s social language that may become its most important contribution to the landscape of film in this day and age. Americans are often allergic to discussion around class. We give vague recognition to it, but our national imagination is largely stuck within identification with middle class values and work ethic. The rich hide behind the middle class and attempt to assume a false humility where as the poor attempt to raise themselves up to the middle class level even though its been shown that poverty engenders different strengths and values than in the middle or upper classes. When we don’t have a full understanding of class dynamics, then we surely don’t have a grasp on how race works within the complexities of varying socio-economic statuses.

As someone who appreciates social commentary done well, it is perhaps the film’s social language that may become its most important contribution to the landscape of film in this day and age. Americans are often allergic to discussion around class. We give vague recognition to it, but our national imagination is largely stuck within identification with middle class values and work ethic. The rich hide behind the middle class and attempt to assume a false humility where as the poor attempt to raise themselves up to the middle class level even though its been shown that poverty engenders different strengths and values than in the middle or upper classes. When we don’t have a full understanding of class dynamics, then we surely don’t have a grasp on how race works within the complexities of varying socio-economic statuses.

It is Boots Riley’s attempt at combining race and class within the narrative of the film that gives the film its importance. Cassius Green’s conflict is not straightforward within the film’s story. It’s not just that his race causes him to be viewed as a second-class citizen within this country, but that he is living in poverty as well. As he rises through the levels of Regalview, his racial identity and his socio-economic status come into conflict within him. In order to rise in the corporation, Cassius has to ignore the corporation’s mistreatment and underpaying of his fellow workers who are diverse in their racial makeup. He is tempted to ignore the class struggle in order to make it as a black man in corporate America, whereas if he sides with Salvador and Squeeze in the class struggle, then excelling in the corporate world as a black man must take a back seat. And, yet, the beauty of the film’s commentary is that the corporations know that these things are both essential parts of the identities of minorities and they choose to exploit them in order to get what they want. They play race against class in order to keep control of their employees and their clients. Something similar could be said of the American government as well.

Companies are ultimately interested in dehumanizing their workers and controlling them by turning elements of their humanity against each other. They don’t need people working for them, but workhorses, or robots, that don’t question their place or the ethics of those in charge. It is the forcefulness and creativity of Riley’s commentary that makes this film work even with its unevenness. It is his social/economic critique that I have pondered since I left the darkened theater and it is this critique that will manifest–if I were to be so bold–in future analysis of this film from here on out. Sorry To Bother You deserves your attention and its questions of identity and ethics demand your thought and that is enough reason to give this film your money.

Companies are ultimately interested in dehumanizing their workers and controlling them by turning elements of their humanity against each other. They don’t need people working for them, but workhorses, or robots, that don’t question their place or the ethics of those in charge. It is the forcefulness and creativity of Riley’s commentary that makes this film work even with its unevenness. It is his social/economic critique that I have pondered since I left the darkened theater and it is this critique that will manifest–if I were to be so bold–in future analysis of this film from here on out. Sorry To Bother You deserves your attention and its questions of identity and ethics demand your thought and that is enough reason to give this film your money.

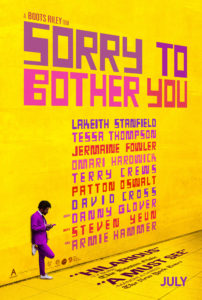

Review| Sorry To Bother You

Previous articleReel World: Rewind #028 - The Princess Bride Next article The Battle for an Ugly World: Se7en (1995) & Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Next article The Battle for an Ugly World: Se7en (1995) & Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Next article The Battle for an Ugly World: Se7en (1995) & Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Next article The Battle for an Ugly World: Se7en (1995) & Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)