“…for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

– George Eliot, Middlemarch

It is difficult to make a film about a conscientious objector or pacifist in the midst of war without glorifying war in the process. Truffaut famously spoke of giving up on directing a cinematic representation of the Battle of Algiers, because “to show something is to ennoble it.”[1] One could look at Mel Gibson’s recent attempt with Hacksaw Ridge to frame the story of Desmond Doss, a pacifist combat medic in World War II, within grand battle sequences. One hyper-stylized moment where Andrew Garfield (who plays Doss) karate kicks a grenade away from a fellow soldier single-handedly compromises the message of the real Doss in order to ennoble the acts of violence that take place within war. To make them “cool.”

It is difficult to make a film about a conscientious objector or pacifist in the midst of war without glorifying war in the process. Truffaut famously spoke of giving up on directing a cinematic representation of the Battle of Algiers, because “to show something is to ennoble it.”[1] One could look at Mel Gibson’s recent attempt with Hacksaw Ridge to frame the story of Desmond Doss, a pacifist combat medic in World War II, within grand battle sequences. One hyper-stylized moment where Andrew Garfield (who plays Doss) karate kicks a grenade away from a fellow soldier single-handedly compromises the message of the real Doss in order to ennoble the acts of violence that take place within war. To make them “cool.”

Even Terrence Malick’s 1999 war film, The Thin Red Line, runs into this problem of ennobling war. Yet his is not making war look cool, but accidentally making war beautiful with wide lens shots of grassland and jungles in the Pacific theater of World War II as the bomb bursts shoot dirt and fire into the sky in a dangerous balletic dance. Even that film has a pacifist character, Pvt. Witt (portrayed by Jim Caviezel), who is battling his conscience in the midst of war and goes AWOL as a result. Malick is able to walk that tightrope more effectively than Gibson, but while there is a very strong anti-war sentiment lodged in the film, its power is somewhat lessened by Malick’s bent towards finding the beauty in the natural world and the destruction taking place within it.

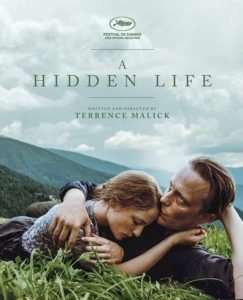

In the midst of an unusually prolific period for Malick’s career, we are given a treat in the form of A Hidden Life; which is a rare attempt at linear storytelling for Malick as he recounts the life of Franz Jägerstätter, a devout Catholic Austrian and farmer who refused to fight for the Nazis in World War II and paid for it with his life. The film’s title comes from the above Eliot quote, but doubles as a potential indictment of celebrity culture: Jägerstätter is not as well-known as, say, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who has fans and adherents in every corner of religious denomination and theology, yet one could make the case that Jägerstätter ended up being the more consistent in how he lived his life within the threat of Hitler’s brutality and repression. However, consistency in such matters means that one’s legacy may not continue in the hearts and memories of humankind. Hence why it is a hidden life.

And this is why Malick’s use of the above Eliot quote at the end of A Hidden Life is so stunning. Jägerstätter was so willing to lose everything, including life with his wife and girls, because he saw the moral deterioration around him, the repression and/or accommodation of the Church by the Reich, and his inability to silence the Spirit that resided in him. If August Diehl’s portrayal is any indication, Jägerstätter was a quiet man who lived a quiet life. He loved his wife and kids deeply. And he took the words of Jesus with utmost seriousness. His faith informed his politics and actions, not the other way around.

And this is why Malick’s use of the above Eliot quote at the end of A Hidden Life is so stunning. Jägerstätter was so willing to lose everything, including life with his wife and girls, because he saw the moral deterioration around him, the repression and/or accommodation of the Church by the Reich, and his inability to silence the Spirit that resided in him. If August Diehl’s portrayal is any indication, Jägerstätter was a quiet man who lived a quiet life. He loved his wife and kids deeply. And he took the words of Jesus with utmost seriousness. His faith informed his politics and actions, not the other way around.

I have been saying to some friends of late that if Malick’s The Tree of Life was his Genesis account then A Hidden Life is his account of the Gospels, for Jägerstätter’s strength was ultimately made perfect in his weakness; and Malick captures the countless moments where Jägerstätter has the opportunity to turn away his cup and not drink of the wrath. The film’s narrative landscape is also punctuated by tiny moments of beauty, love, friendship, and glory. And underscored with loss, such as when Jägerstätter’s wife, through tears, faithfully commits to her love’s actions even if their result is her loss, their kids’ loss.

Malick’s characteristic attention to the human moments and the beauty of nature that shrouds the human drama taking place in its midst is retained here in the stunning Austrian mountainsides. Just like The Tree of Life used imaginative cinematic visions of the universe’s creation to place the story of the O’Briens within an unfolding cosmic story, A Hidden Life uses actual footage of Hitler, Nazi parades, and war to fill out the unfolding story of cosmic evil that began to creep into Germany and then Europe starting in the 1930s.

How Malick renders context in his films is like no other director alive today and it feels similar to how one reads the accounts of Christ’s life in the Gospels. Jesus is this unassuming man—both God and man, we’re told—who is humble and mild, yet does not equivocate when it comes to the will of the Hebrew God, who we are told is his Father. Yet no matter how much good he does, no matter how many miracles he performs, he ends up on a cross, crucified, mangled, and dead, but innocent. The Gospels build this context around this God-man by giving us a picture of the power dynamics, the give and take of the Jewish and Roman leaders in the region, and the ultimate events leading to Jesus’ death. Both of these stories present a context that is suffocating in its violence, power, and control, yet these stories present similar protagonists who faithfully go to their death. They both, through the lens of human reason and wisdom, are foolish. How can one do good, change things, and defeat evil by going to their death? This is a question we will never fully know, but it seems Eliot may be right in that the countering force of good in this world is not found in showy actions or grand public gestures of justice and mercy, but in the faithful actions of everyday people who are hidden from the public eye and “rest in unvisited tombs.”

How Malick renders context in his films is like no other director alive today and it feels similar to how one reads the accounts of Christ’s life in the Gospels. Jesus is this unassuming man—both God and man, we’re told—who is humble and mild, yet does not equivocate when it comes to the will of the Hebrew God, who we are told is his Father. Yet no matter how much good he does, no matter how many miracles he performs, he ends up on a cross, crucified, mangled, and dead, but innocent. The Gospels build this context around this God-man by giving us a picture of the power dynamics, the give and take of the Jewish and Roman leaders in the region, and the ultimate events leading to Jesus’ death. Both of these stories present a context that is suffocating in its violence, power, and control, yet these stories present similar protagonists who faithfully go to their death. They both, through the lens of human reason and wisdom, are foolish. How can one do good, change things, and defeat evil by going to their death? This is a question we will never fully know, but it seems Eliot may be right in that the countering force of good in this world is not found in showy actions or grand public gestures of justice and mercy, but in the faithful actions of everyday people who are hidden from the public eye and “rest in unvisited tombs.”

While men like Bonhoeffer have a stunning legacy of writing that we can learn from, it strikes me that Jägerstätter’s legacy is found in his largely unknown (until now) sacrifice. We can’t see the effects of his sacrifice, just like we couldn’t at the time of Christ’s death, but God uses things unseen to do Kingdom work. God uses foolishness to shame the wise, the powerful, the strong. Malick presents a gorgeous immersion into the life of this man. Outside of perhaps Calvary, A Hidden Life might be the greatest story of faith put to celluloid and continues the vision of one of our generation’s greatest directors.

[1] Baecque, François Truffaut, p.164.

1 comment