There is this detail that runs through André Øvredal’s adaptation of the classic 80s young adult horror anthology series, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark; which anchors it to the year in which the film is set, 1968. The television sets are all tuned to two distinct but interrelated news items: the campaign and eventual victory of Richard Nixon over Hubert Humphreys for president, and the Vietnam conflict wherein the United States had already increased their presence from 16,000 to nearly 550,000 by the time this film takes place. I did not grow up with this series of books, so I have no idea what elements from the books were present in the film and what parts were not. However, I do know that choosing 1968—in the USA—cannot be arbitrary.

There is this detail that runs through André Øvredal’s adaptation of the classic 80s young adult horror anthology series, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark; which anchors it to the year in which the film is set, 1968. The television sets are all tuned to two distinct but interrelated news items: the campaign and eventual victory of Richard Nixon over Hubert Humphreys for president, and the Vietnam conflict wherein the United States had already increased their presence from 16,000 to nearly 550,000 by the time this film takes place. I did not grow up with this series of books, so I have no idea what elements from the books were present in the film and what parts were not. However, I do know that choosing 1968—in the USA—cannot be arbitrary.

Take away this detail from the film and what remains is a delightful horror flick that threads the needle of tone throughout. It’s never too violent or grotesque, but it has just enough of an edge to tell the audience that it means business. It doesn’t intend to pull all of its punches. But as we move through the story with our hapless crew of teenagers—Stella, Ramon, Auggie, Chuck, Ruth, and Tommy—attempting to solve and confront the entities and mysteries that begin to kill them one by one, our national consciousness is jogged by the actual images of these real events going on in the world around them. Specters loiter in the flickering shadows of the American existence portrayed in the film. One of our characters is, as we come to find out, dodging the draft himself. The television airwaves within the film are scraping the pavement of the reality of the viewer’s world. The only thing left that could have been included would have been the assassination of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, which would have taken place 7 months prior to the events of the film. That death still loomed large at this point, as the Civil Rights movement rallied in its wake. As these (mostly Northern white) teenagers avoid their fears made flesh by the transcendent rage of Sarah Bellows, the world around them is witnessing its own rage made manifest in front of them. One could say that del Toro and Øvredal are making a point to draw a line between Sarah Bellows and the United States, a rage that is destroying the innocent, the hurt, the downtrodden. The rage that is built off of a lie.

This little reminder throughout the film was a nice little touch for what could have easily been a glossy piece of nostalgic horror fare like IT: Chapter 1. It grounded the film in a reality where evils are both natural and supernatural. There are powers and principalities, both in a religious and social sense. Evil sometimes wins. Evil is sometimes misunderstood. Evil comes from outside as well as inside. This is an important reminder in this day and age when it is quite easy to take opposition merely on materialistic grounds. We resist governments, presidents, groups, etc. because they enact evil on people; however, we forget that there is an unseen element behind all of those actions that must not be forgotten. I won’t say it’s the Devil, for my more progressive Christian readers out there, but there is some form of immaterial malevolence out there. Unseen forces move in this world. Scary Stories… goes further than it had to in order to remind its audience that both pose a threat.

This little reminder throughout the film was a nice little touch for what could have easily been a glossy piece of nostalgic horror fare like IT: Chapter 1. It grounded the film in a reality where evils are both natural and supernatural. There are powers and principalities, both in a religious and social sense. Evil sometimes wins. Evil is sometimes misunderstood. Evil comes from outside as well as inside. This is an important reminder in this day and age when it is quite easy to take opposition merely on materialistic grounds. We resist governments, presidents, groups, etc. because they enact evil on people; however, we forget that there is an unseen element behind all of those actions that must not be forgotten. I won’t say it’s the Devil, for my more progressive Christian readers out there, but there is some form of immaterial malevolence out there. Unseen forces move in this world. Scary Stories… goes further than it had to in order to remind its audience that both pose a threat.

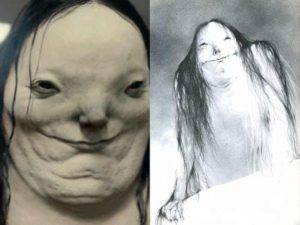

Within this elevated sense of setting, we must ask if the film itself works. Is it entertaining, compelling, enjoyable, so on? Øvredal accomplishes his vision in spades. He, along with producer Guillermo del Toro, were smart to remain faithful to the images conjured by original series illustrator Stephen Gammell. Their rendering on the silver screen felt outside of time. They felt simple, yet effective, in a way that most horror entities are not presented in this day and age. They even felt real in a practical sense, though CGI was heavily used throughout the film; in contrast with the CGI of Stranger Thingsor IT, which became so infatuated with what they could do that they forget to ask if it was actually warranted by the story. The old adage, “less is more,” continues to be a wise proverb that Hollywood should really solidify in their culture.

The interplay of good-natured, simple narrative with restrained yet effective CGI and a nice little nasty edge allows for the film to strike a perfect balance between the R.L. Stine-style horror for kids and the majority of horror cinema that is released during the year. More keen viewers will catch an added depth via the film’s setting and atmosphere that only adds to the suffocation of the characters who are our avatars as they confront these horrors. The history that teases itself throughout the film is not promising and doesn’t end well—with corruption, scandal, war crimes, atrocities, thousands dead—the film shows that evil can be conquered, if only for a time. It will never go away completely, and the memories of it will linger into the future as it does in the life of Stella, her father, and Ruth; just as it does in the real historical narrative of American history.

The interplay of good-natured, simple narrative with restrained yet effective CGI and a nice little nasty edge allows for the film to strike a perfect balance between the R.L. Stine-style horror for kids and the majority of horror cinema that is released during the year. More keen viewers will catch an added depth via the film’s setting and atmosphere that only adds to the suffocation of the characters who are our avatars as they confront these horrors. The history that teases itself throughout the film is not promising and doesn’t end well—with corruption, scandal, war crimes, atrocities, thousands dead—the film shows that evil can be conquered, if only for a time. It will never go away completely, and the memories of it will linger into the future as it does in the life of Stella, her father, and Ruth; just as it does in the real historical narrative of American history.