While the 80s might have had the shine and mythology of excess given to it from the rearview mirror of history, the 90s, by most appearances, lived in the full realization of that mythology. The thing that distinguished it from the 80s was that the underbelly and decay within the nation would not stay hidden much longer. Perhaps the most fascinating juxtaposition is how African American filmmakers and women filmmakers were starting to make their presence known in the midst of an industry that catered to the ever-growing superstar actor, most of whom were white males and some white females. Stars like Demi Moore, Julia Roberts, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Mel Gibson, and Tom Cruise forced studios to pay for jets, masseuses, hair, make-up, among other luxuries during press tours. It was also not rare for actors and actresses to ask for script approval before they would fully sign on to do the film.

While the 80s might have had the shine and mythology of excess given to it from the rearview mirror of history, the 90s, by most appearances, lived in the full realization of that mythology. The thing that distinguished it from the 80s was that the underbelly and decay within the nation would not stay hidden much longer. Perhaps the most fascinating juxtaposition is how African American filmmakers and women filmmakers were starting to make their presence known in the midst of an industry that catered to the ever-growing superstar actor, most of whom were white males and some white females. Stars like Demi Moore, Julia Roberts, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Mel Gibson, and Tom Cruise forced studios to pay for jets, masseuses, hair, make-up, among other luxuries during press tours. It was also not rare for actors and actresses to ask for script approval before they would fully sign on to do the film.

When large chunks of a film’s budget are going to the creature comforts of the most loved and revered actors and actresses of the decade, it became very easy for filmmakers to lose control of their budgets and then their films. It didn’t help that studios were aiming for big tent pole pictures as often as possible. Films with chase scenes, battles, CGI, and big stars were the assured moneymakers. However, as the price of making them began to grow throughout the decade, the profit margins were starting to tighten up as the industry was dealing with the growing pains of a slowly increasing number of screens throughout the country. Multiplexes were going up right and left in order to provide more screens and showtimes in order to recuperate their costs, if not expand their chances at profit.

Meanwhile, in other parts of Hollywood, studios were beginning to see the power of small, independent cinema. Many studios opened up their own independent branches like Fox Searchlight, the Independent Film Channel, and the Sundance Film Festival and Channel were showing the power of simpler forms of narrative, character, acting, and filmmaking while still telling compelling stories that would make money. It would seem that mainstream cinema was driven by the American populist sensibility with little general variation from film to film—especially with the deluge of action films and CGI-heavy disaster films. The independent studios were reclaiming the more theoretical realms of filmmaking. The auteur theory became key with the likes of Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, and Lars von Trier, all directors who became known Hollywood names by the end of the decade. It was the independent picture that was concentrating what film was at its core when stripped away of the often unnecessary technology which had exploded in the industry in the 70s and 80s.

Meanwhile, in other parts of Hollywood, studios were beginning to see the power of small, independent cinema. Many studios opened up their own independent branches like Fox Searchlight, the Independent Film Channel, and the Sundance Film Festival and Channel were showing the power of simpler forms of narrative, character, acting, and filmmaking while still telling compelling stories that would make money. It would seem that mainstream cinema was driven by the American populist sensibility with little general variation from film to film—especially with the deluge of action films and CGI-heavy disaster films. The independent studios were reclaiming the more theoretical realms of filmmaking. The auteur theory became key with the likes of Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, and Lars von Trier, all directors who became known Hollywood names by the end of the decade. It was the independent picture that was concentrating what film was at its core when stripped away of the often unnecessary technology which had exploded in the industry in the 70s and 80s.

With the rise of hip hop culture in the five boroughs of NYC in the late 80s and early nineties and the subsequent effects of the war on drugs on urban areas along with public displays of police brutality, African American voices were beginning to force themselves into the cultural milieu. A disproportionate amount of black men were being thrown into prison while rich, white families like the Sacklers were offloading opioids to the masses and using their power to cover up their place in a growing crisis that is just now coming to a head. In other  words, the US government was fine with giving the impression of being “hard on crime” by increasing the number of arrests of low-level dealers even though the inventory was often coming from white individuals, families, and companies who were able to hide behind the monstrous imagery of the criminalized black man created during the war on drugs. The issues that were worsening but remaining hidden during the 80s were about to burst into the cultural spheres. It didn’t help that current events like the Central Park 5 and the trial of Anita Hill were spurring on some of those conversations, though not necessarily asking the same questions that those events evoke in us now. Nonetheless, the voiceless were starting to find their voice and they refused to be quiet any longer. Spike Lee is probably the most well-known and continually outspoken example of an African American director who got started with independent features like Do The Right Thing and began to move up into more mainstream fare like Malcolm X. He has continued to be a thorn in a still largely white Hollywood establishment and it was his and a handful of other people of color in the 90s that would make way for more diverse voices to be heard.

words, the US government was fine with giving the impression of being “hard on crime” by increasing the number of arrests of low-level dealers even though the inventory was often coming from white individuals, families, and companies who were able to hide behind the monstrous imagery of the criminalized black man created during the war on drugs. The issues that were worsening but remaining hidden during the 80s were about to burst into the cultural spheres. It didn’t help that current events like the Central Park 5 and the trial of Anita Hill were spurring on some of those conversations, though not necessarily asking the same questions that those events evoke in us now. Nonetheless, the voiceless were starting to find their voice and they refused to be quiet any longer. Spike Lee is probably the most well-known and continually outspoken example of an African American director who got started with independent features like Do The Right Thing and began to move up into more mainstream fare like Malcolm X. He has continued to be a thorn in a still largely white Hollywood establishment and it was his and a handful of other people of color in the 90s that would make way for more diverse voices to be heard.

It truly is this dichotomy of the overblown price tags of white movie stars and the growing discomfort with the status quo for people of color that was starting to take place in the independent film realms. Not to mention the growing mixture of hip hop/gangster rap and horror that would get its start in the 90s. Many of the elements of modern Hollywood that we are beginning to see take hold today started to take root in the 90s.

It truly is this dichotomy of the overblown price tags of white movie stars and the growing discomfort with the status quo for people of color that was starting to take place in the independent film realms. Not to mention the growing mixture of hip hop/gangster rap and horror that would get its start in the 90s. Many of the elements of modern Hollywood that we are beginning to see take hold today started to take root in the 90s.

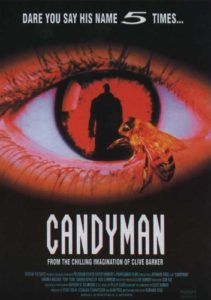

Perhaps one of the more interesting examples of “blacks in horror” film—as defined by Robin R. Means Coleman in Horror Noire—from the 90s is the 1992 Bernard Rose-directed Candyman. The film stars Tony Todd as the titular character who becomes obsessed with Helen, a young white grad student played by Virginia Madsen. This film is perhaps the only significant entry in a filmography by Rose which is filled with 80s music videos, softcore porn, and straight-to-video flicks. Normally this doesn’t bode well for a film about the son of a slave who was murdered for having affairs with a white woman. However, something must have struck Rose for this film, because it stands up to the test of time—except perhaps the blunt exposition that Madsen delivers about police impunity towards whites that black people seldom receive. While true, the statement felt like a political slogan that could have easily been shown, not spoken. On the whole, the film plays seamlessly while digging into subjects that were seldom dealt with at this point in the decade—except for maybe The People Under The Stairs.

For those who haven’t seen it, how Candyman plays out is something akin to the typical “are they/aren’t they” going crazy thrillers that have been the bread and butter of horror screenings for a long time. As Candyman claims each of his victims after they say his name five times in a mirror, everyone is led to believe that Helen is committing the crimes as she tends to have the weapon or type of weapon used to kill them in her possession at the scene. Candyman, however, continues his obsession with her and asks her to “be his victim.” Basically to join him as a type of reincarnated lover (since there was a resemblance), but she has to be convinced of the power of myth first which means being the subject of every person’s disbelief. Even her philandering husband ends up not believing her by the time the conclusion happens. She is never believed and as she continually tries to convince them of her innocence, she becomes more possessed by a relinquishment to her fate as the “mythological other.”

For those who haven’t seen it, how Candyman plays out is something akin to the typical “are they/aren’t they” going crazy thrillers that have been the bread and butter of horror screenings for a long time. As Candyman claims each of his victims after they say his name five times in a mirror, everyone is led to believe that Helen is committing the crimes as she tends to have the weapon or type of weapon used to kill them in her possession at the scene. Candyman, however, continues his obsession with her and asks her to “be his victim.” Basically to join him as a type of reincarnated lover (since there was a resemblance), but she has to be convinced of the power of myth first which means being the subject of every person’s disbelief. Even her philandering husband ends up not believing her by the time the conclusion happens. She is never believed and as she continually tries to convince them of her innocence, she becomes more possessed by a relinquishment to her fate as the “mythological other.”

It is almost as if Helen must be stripped of her privileges and become like Candyman in order for her to truly become “his victim” and to join him. However, Helen ends up leaving Candyman in the pyre of the used possessions of Cabrini Green—a desolate urban project where Candyman was murdered many years before. The white woman rejects him, lets him burn, and the most intriguing turn in the film, whether intentional or not, is she, too, dies in the act of saving the black baby of a resident of Cabrini Green. What is so fascinating about this move is that the film showcases a white savior—because for a good portion of time, cinema seldom showed white people as all bad in the context of a racial story—that dies and comes back to haunt and kill her husband like Candyman would. He says Helen’s name 5 times in his despair (surprisingly!) and she disembowels him. She not only gets to play the white savior in the film, but she ultimately gentrifies the realm of the black villain. She claims his powers after killing him to wreak her own vengeance on those who made her privileged life a living hell.

It is almost as if Helen must be stripped of her privileges and become like Candyman in order for her to truly become “his victim” and to join him. However, Helen ends up leaving Candyman in the pyre of the used possessions of Cabrini Green—a desolate urban project where Candyman was murdered many years before. The white woman rejects him, lets him burn, and the most intriguing turn in the film, whether intentional or not, is she, too, dies in the act of saving the black baby of a resident of Cabrini Green. What is so fascinating about this move is that the film showcases a white savior—because for a good portion of time, cinema seldom showed white people as all bad in the context of a racial story—that dies and comes back to haunt and kill her husband like Candyman would. He says Helen’s name 5 times in his despair (surprisingly!) and she disembowels him. She not only gets to play the white savior in the film, but she ultimately gentrifies the realm of the black villain. She claims his powers after killing him to wreak her own vengeance on those who made her privileged life a living hell.

There is a unique interplay of race dynamics running through the film. The detective on the case is black, her best friend and research partner is black, and she is seemingly a good liberal academic who believes in justice for all. Yet she ends up falling into the same trap as those who don’t have her same values on paper. Even in the midst of her turn towards the white savior who gentrifies Candyman’s powers, Candyman instills one lesson in her, at the very least: if you are not a white male, you won’t be believed in society. Hence she is potentially able to justify her gentrification depending on how one reads her  position in the modern racial and gender hierarchies. The film ends up being a much more nuanced—though perhaps not intentionally so—take on the interplay of race and gender. How you rank the hierarchies of race, gender and sexuality in the current climate will determine how you read the conclusion of this film. This is why I find the film continues to hold up. It (accidentally?) navigates a mire of complexities that will baffle nearly every position.

position in the modern racial and gender hierarchies. The film ends up being a much more nuanced—though perhaps not intentionally so—take on the interplay of race and gender. How you rank the hierarchies of race, gender and sexuality in the current climate will determine how you read the conclusion of this film. This is why I find the film continues to hold up. It (accidentally?) navigates a mire of complexities that will baffle nearly every position.

While it is a safer bet to allow black people to tell their own authentic black narratives—and the benefit that has for film overall, especially horror—it isn’t impossible for good, complex narratives to be weaved by white directors (and other creators) whether intentionally or not. Bernard Rose clearly had some thoughts on the subject, but he was also stuck in a specific time. Yet the text of a film can sometimes outlast the short-sightedness of its creator. Candyman is definitely one of those films. Viewing it again has made me excited to see what a “spiritual sequel” of the film can look like with a black female director. Here’s hoping that the complexities of this story enchant a new generation.