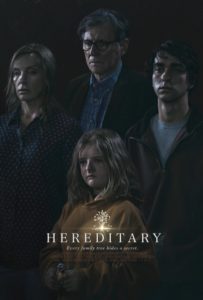

Hereditary is proving both a critical and commercial success. It’s boasting over 90% on RottenTomatoes and the best opening weekend for studio A24 (and on track to be A24’s second-most successful film, after Ladybird). The film centers on a family who has lost their estranged grandmother. We learn they also have a legacy of mental health issues, which quickly devolve into something more sinister.

Hereditary is proving both a critical and commercial success. It’s boasting over 90% on RottenTomatoes and the best opening weekend for studio A24 (and on track to be A24’s second-most successful film, after Ladybird). The film centers on a family who has lost their estranged grandmother. We learn they also have a legacy of mental health issues, which quickly devolve into something more sinister.

That “something more sinister” proves to be demonic. I’ve been a horror fan my whole life; growing up, I proudly waited every month for R. L. Stine’s latest Goosebumps book at my local bookstore. Loving both ghosts and the Holy Ghost, I’ve heard more times than I can count some version of, “But should Christians really be watching movies about demons?!”

There’re some good critics of films like Hereditary that conflate Possession and Mental Illness (I addressed that more fully for Think Christian). But that’s not what a lot of Christians are worried about (unfortunately, we have a long way to go in the Church when it comes to addressing mental health faithfully).

No, Christians are worried most often that movies about demons somehow contaminate or taint faithful believers. I’ve been warned plenty that to partake of The Exorcist or The Exorcism of Emily Rose or The Last Exorcist (and its unfortunately named sequel The Last Exorcist Pt 2) and, yes, Hereditary is “opening myself up to the demonic.”

No, Christians are worried most often that movies about demons somehow contaminate or taint faithful believers. I’ve been warned plenty that to partake of The Exorcist or The Exorcism of Emily Rose or The Last Exorcist (and its unfortunately named sequel The Last Exorcist Pt 2) and, yes, Hereditary is “opening myself up to the demonic.”

Is that right? Should Christians watch films about demon possession?

Maybe that’s the wrong question. Since this is Reel World Theology, what if we asked, “What can we learn from possession films?”

First, a caveat: if you’re not into horror, I’m in no way advocating you have to watch possession films (what a weird thing to try to claim!). If they’re not your bag, don’t let me pressure you to partake.

That said, let’s grab an old priest and a young priest and explore Possession films. First, what function does horror play in culture? (Not just our culture, but in every human culture. We all tell monster stories. Why?)

The word monster comes to us from the Latin word monstrum, which means ‘omen’ or ‘warning’. Monsters point at something hidden. Historian Scott Poole, in his landmark work Monsters in America, observes that monster stories expose the master narratives that otherwise prove difficult to spot. “[Monsters] are the things hiding in history’s dark places, the silences that scream if you listen close enough.” Cultural critic Greil Marcus writes that “parts of history because they don’t fit the story a people wants to tell itself, survive only as haunts and fairy tales, accessible only as specters and spooks.”

The word monster comes to us from the Latin word monstrum, which means ‘omen’ or ‘warning’. Monsters point at something hidden. Historian Scott Poole, in his landmark work Monsters in America, observes that monster stories expose the master narratives that otherwise prove difficult to spot. “[Monsters] are the things hiding in history’s dark places, the silences that scream if you listen close enough.” Cultural critic Greil Marcus writes that “parts of history because they don’t fit the story a people wants to tell itself, survive only as haunts and fairy tales, accessible only as specters and spooks.”

What does it mean, then, that we tell stories about demons? Demon stories often reveal cultural anxieties about systemic changes. Rosemary’s Baby, the 1968 Roman Polanski film about Satan’s baby, reflected and fed into anxieties about reproductive rights, a shift that had begun less than a decade earlier when the FDA approved the birth control pill and would become explosive with the Roe v. Wade ruling of 1973.

1973 saw the debut of another classic film about the demonic: The Exorcist. William Friedkin’s Best Picture winner adapted a novel based on the true story of a St. Louis boy. The film (and novel) make two notable changes to the true story: the possessed child becomes a girl, and her parents are divorced. Regan grows up without a father, leaving her open to demonic possession (and needing rescue from two Fathers). Coming in the wake of the Free Love movement of the 60s, The Exorcist embodied socially conservative anxiety about the breakdown of the nuclear family.

More recent possession films do the same, from 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose (also based on a true story) musing on why innocent children suffer, to 2014’s Deliver us from Evil, which suggests that the way we treat our returning war veterans is diabolical.

More recent possession films do the same, from 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose (also based on a true story) musing on why innocent children suffer, to 2014’s Deliver us from Evil, which suggests that the way we treat our returning war veterans is diabolical.

When we experience a film like Hereditary, then, we ought not ask, “Is this film blaming mental illness on demons?” We should ask, “What does this omen portend?” What systemic anxiety or evil is the film using demons to point to?

The most recent celebrity suicides and school shootings by angry white boys insist we take mental health more seriously than we are. It’s easier to demonize them, to protest that a person who dies by suicide is selfish or that the school shooter was an anomalous monster.

Hereditary embodies these anxieties, envisioning familial demons as literal. Woe to those of us who settle for a theatrical chill and ignore the warning: families who suffer from mental illness often suffer in silence, in large part because of the stigma mental illness continues to carry in our churches. We should be about the healing of all kinds of bondage—physical, spiritual, emotional and mental. Hereditary is just a (very) scary movie, but real families live with real trauma as their daily realities.

Monster films—and this goes double for the demonic—are tremendous diagnostic tools. They reveal our cultural anxieties, dragging them into the light. Those of us who know the Great Physician should take careful note, that we might enter the conversations they begin as voices of hope and healing.