Wherever historians would like to place the actual year of the first “film,” its beginnings were firmly in the 1890s. Between Edison’s phonograph, Dickson’s kinetograph and the Lumière brothers’ commercialization of their projectors with the  cinématographe, the moving picture was well on its way by the turn of the new century. Many of these early films, especially in the 1890s, were no longer than 6-7 minutes and were less about continuity and narrative and more about playing tricks on the mind through the audience’s visual experience.

cinématographe, the moving picture was well on its way by the turn of the new century. Many of these early films, especially in the 1890s, were no longer than 6-7 minutes and were less about continuity and narrative and more about playing tricks on the mind through the audience’s visual experience.

George Méliès, a professional magician, saw this as his chance to bring magic into the 20th century. The ultimate trick where insiders were the only one who knew how it was done. However, when the Lumières snubbed the magician, Méliès decided to buy another projector—an animatograph—and reworked it in order to do what he needed. Most of his films were stop-motion where the strip could be stopped and items could be scrubbed or placed back in to give a quick cut, jerky feel to the films. However, to the audiences lucky enough to view these little worlds, they were ushered into a new reality that affected them.

It was no surprise then that Méliès would lean towards horror—and comedy—to give motion pictures the ability to make people feel shock or terror without putting them in actual danger. It is also not much of a surprise that the main content of horror in those days consisted of infernal beings, especially the devil himself. The ringleader of all the things that go bump in the night. How does one defeat the devil? Traditionally, the answer has been through Christian ritual, symbols, word and sacrament. The saints overcame the ‘prince of the air’ by faith in the cross and the power that flows from it. Early horror was deeply and overtly steeped in the religious imagery of spiritual warfare between the powers of good and evil.

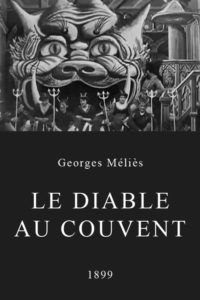

Méliès’ 1899 feature, Le Diable au couvent, is an exemplar of the type. Its jerky, worn, black and white celluloid world is opened and closed to us in three minutes and eleven seconds, however it encompasses everything from heaven to hell and the frightened, yet emboldened, faithful caught in the middle.

The devil’s presence is not unlike many characterizations in plays and ballets through the years. He is dressed in tights and attire akin to fashion in the Elizabethan era and he is given the typical facial hair to denote his sinister devices. He is a trickster and shifts into the form of the priest to lead the nuns astray during what seems like a daily prayer meeting. He makes a mockery of their sacred space and invites his minions to partake in revelries surrounded my hellish icons set up all around. The devil rides a giant frog in the midst of the infernal affair denoting the link between frogs and curses from Exodus and hell in the imagery of Dante’s Inferno. None of this imagery is new, even to the modern viewer. It’s what is to be expected in the devil’s playground.

The devil’s presence is not unlike many characterizations in plays and ballets through the years. He is dressed in tights and attire akin to fashion in the Elizabethan era and he is given the typical facial hair to denote his sinister devices. He is a trickster and shifts into the form of the priest to lead the nuns astray during what seems like a daily prayer meeting. He makes a mockery of their sacred space and invites his minions to partake in revelries surrounded my hellish icons set up all around. The devil rides a giant frog in the midst of the infernal affair denoting the link between frogs and curses from Exodus and hell in the imagery of Dante’s Inferno. None of this imagery is new, even to the modern viewer. It’s what is to be expected in the devil’s playground.

Where the film takes a turn is in the defeat of the devil’s control over the convent. In a highly individualized American society, we view several films where the devil attacks or possesses and we find a courageous priest or person fending off his infernal imperialism, sometimes with a divine trinket or cross, but seldom with God given full credit as the driving force. “God only helps those who help themselves” is the mantra of most of these cinematic narratives. Yet Le Diable au couvent tells a different story that corrects that pithy saying without denigrating the part we do play in the battles for the kingdom.

We see a process of exorcism that begins with the nuns taking back their convent. A singular nun dressed in a full white habit—face fully obscured by a veil—comes forward, cross in hand, in the midst of the diabolical merriment and the minions, whom compelled by the power of the cross, are forced back and dissipate into the air. They are no match for the nun’s faith. The devil is whiplashed as he holds his arms up against the symbol of his enemy. As he spins around the space to escape we are met with what I consider to be the best scene of the film: three more nuns with crosses pop up one after another as the devil circles to escape. The scene easily rivals the best of the quick-cut, jump scares of today. They surround him, and he falls to the ground, but the nuns are then defeated. The devil causes them to disappear and he seems revived and without harm. The faith of the nuns alone was not enough to tear down the ‘powers and principalities.’

Then comes a guard for the convent, a civil authority, who chases the devil around to no avail. He has even less effect on the devil than the nuns. He is dissipated into thin air as well. The civil authorities are completely useless against the darkness that lurks behind the curtain of the city of man.

Then comes a guard for the convent, a civil authority, who chases the devil around to no avail. He has even less effect on the devil than the nuns. He is dissipated into thin air as well. The civil authorities are completely useless against the darkness that lurks behind the curtain of the city of man.

Finally, we see the priest come forth and try to run the devil out. The priest whose form the devil took at the beginning of the picture. The devil’s interaction with the priest is perhaps the most intriguing. It plays like a Marx Brothers or Three Stooges slapstick set piece where the devil always gets the upper hand over the priest, but instead of hurting him he just taps him, playfully, on the head with his foot or from behind with his hand. The devil is having fun with the priest. It is stunning for a film in 1899 to have a, perhaps unintended, message that it is those in the lower realms of the church’s hierarchy whose faith is more active and strong. In this case, the nuns though defeated are the closest to making a mark on the devil’s progress. Why are the holy in this film so ineffective against the whims of the demonic?

One possibility might be the historical moment in which Méliès found himself placed within France’s history. There was a general weakening of the Catholic Church in France by the French Republicans who saw the church as too powerful and having too many class associations. Lay women were replacing nuns at hospitals, priests were kept from being on hospital and charity committees and other anti-Catholic policies were enacted. Méliès may have chosen to show the result of these types of policies within the world of spiritual warfare. The nuns are defeated, though not frustrated, and the priest is defeated and made into a mockery. The film came out three years before Émile Combes, the new prime minister, set out to thoroughly destroy Catholicism in France. This was not a bright moment for the French Catholics and the visions of a dwindling church might have given Méliès the idea for the film.

Another reason why the holy are ineffective in the film is more theological in its speculation. What takes the devil down is the procession of the Word into the convent and the miraculous appearance of St. Michael—or rather a living statue of the saint—who bears down on the devil with a spear and forces the devil to disappear as he had made all the humans who struggled with him before do. The divine intervened after being ushered in by the holy saints of the parish. The devil is defeated by God (and his messengers).

Being an Anglican at heart, the procession of the Word as it goes down the aisle (amongst the people) and the Gospel is read strikes a chord. It is a reminder that the being of God is both shown to us through the word and through the sacrament—or what I like to call God’s movement. While God is present all the time, in all places, this does not mean it is always felt by people. This moment in a Catholic,  Anglican and Lutheran service gives so much meaning and awakening to that reality. Le Diable au couvent presents, then, another form of God’s movement in the life of the faithful: the savior. The actual full salvation of God looked less like victory and more like defeat, but in the wake of Christ’s death and resurrection we know that the devil is spinning his wheels until his final end. I imagine it wouldn’t be too far of a stretch to see Saint Michael, the archangel, carry out that final end as we saw in this film.

Anglican and Lutheran service gives so much meaning and awakening to that reality. Le Diable au couvent presents, then, another form of God’s movement in the life of the faithful: the savior. The actual full salvation of God looked less like victory and more like defeat, but in the wake of Christ’s death and resurrection we know that the devil is spinning his wheels until his final end. I imagine it wouldn’t be too far of a stretch to see Saint Michael, the archangel, carry out that final end as we saw in this film.

Take heart, dear reader, Le Diable au couvent is just one more reminder to us all. We can strive against and struggle with the forces of darkness—even the devil himself—but we must remember that salvation, as the Word says, is the Lord’s. And the best part of that promise is that it is already finished. On that one day, the devil shall make mockeries of us no more.