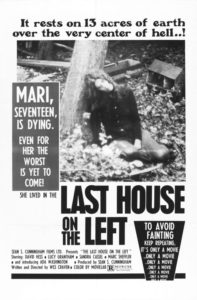

The tension between the sadistic and masochistic appeals of horror was reflected in the divide between Cunningham and Craven. The producer saw LAST HOUSE as an escape, an outlet for some dormant pain. As it happens, he also knew that allowing the audience to feel like a monster could make some money. But Craven, raised in an evangelical household, had a much deeper feel for the allure of self-sacrifice, of seeing abuse and brutality as transcendent. When people went to church, they were not merely escaping pain. They were brave enough to confront it, and that gave them a certain feeling of triumph. The trick was to find what scares could trigger a response from a secular audience looking of the pleasure of masochism. THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT challenged one of the most basic assumptions about the relationship between the audience and the filmmaker—namely, that people go to movies to enjoy themselves. — Jason Zinoman, Shock Value (pg. 77)

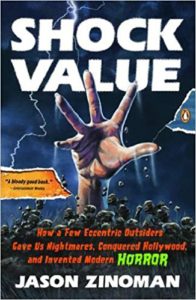

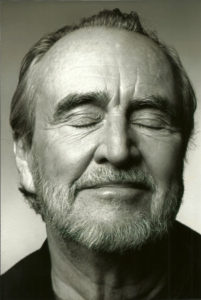

I have written on the thoughtfulness of Wes Craven elsewhere, but when I read Shock Value the above quote caught my attention and shot my mind into a sort of tunnel vision. Jason Zinoman unearthed a (red) cord of reasoning in Craven’s The Last House on the Left–and really subsequent films by Craven and other directors of “New Horror”–I had not really explored in depth. Zinoman, I believe, is right about the act of walking into church, partaking in the service and sacraments and being open to the word of God as mediated through the very human lips of the pastor/priest. It was not escapism, but confrontation, not entertainment, but severe acknowledgment about ourselves. At least, this is the seriousness and heaviness that should accompany that act of entering into the symbolic house of God.

I have written on the thoughtfulness of Wes Craven elsewhere, but when I read Shock Value the above quote caught my attention and shot my mind into a sort of tunnel vision. Jason Zinoman unearthed a (red) cord of reasoning in Craven’s The Last House on the Left–and really subsequent films by Craven and other directors of “New Horror”–I had not really explored in depth. Zinoman, I believe, is right about the act of walking into church, partaking in the service and sacraments and being open to the word of God as mediated through the very human lips of the pastor/priest. It was not escapism, but confrontation, not entertainment, but severe acknowledgment about ourselves. At least, this is the seriousness and heaviness that should accompany that act of entering into the symbolic house of God.

As with most things in the West–and specifically America–these actions have been depleted and weakened by saccharine sweetness and passivity among the church (universal) in the last several years. The church has failed to viscerally confront the sinner in us all. Entering church no longer requires courage on the part of people. Instead, it retains no differences from a social or country club. If Zinoman is right, then horror has intervened as the new sacred altar where sinners bravely fill the pews and are confronted with the truth of their existence and being.

The Last House on the Left showcases a narrative that does not look away from the violence, humiliation and cruelty of human beings towards each other. It is a stark tale of revenge where a gang kidnap two girls and proceed to rape one, while forcing the other to watch, humiliating them both with acts of utter cruelty and, finally, killing them both. The vicious people end up in the home of the parents of the raped girl and, too, fall victim to violent, bloody, cruel acts of vengeance at the hands of the parents. Craven finds a way, early on, to humanize the members of the gang even as they do heinous things to the girls. He does this in order to offset the audience’s natural inclination to side with the “justified vengeance” of the parents.

The audience is confronted by a truth that hasn’t been effectively and viscerally delivered from the pulpit or felt by the congregation in years. The parents ultimately become the very thing they despise, the very thing that violently killed their daughter. The Last House on the Left leaves no room for self justifications, the audience is forced to acknowledge their base natures and see that through their cathartic need for bloodlust, they, somewhere deep down, have the potential to become the very monsters they publicly curse. Craven accomplishes this by making sure that the audience is experiencing the film from the perspective of those doing the cruelty and killing throughout the runtime.

If audiences were identifying with killers, then how does that change our understanding of horror? One disturbing conclusion that received a boost with the popularizing of Freudian analysis of dreams is that scary movies allow audiences to express their repressed sinful thoughts through the monster. We like movies about killing because on some subconscious level we want to kill. (Zinoman, 77).

The film, according to this analysis, made us identify, and live vicariously through, the gang members as they rape, humiliate and kill the girls–this is done by the camera’s persistent focus on the terrified faces of the girls–and then as the gang members are hacked, chopped and killed by the “civilized” parents. For the audience to be truly affected by the narrative, they must identify with the monsters. When that identification takes place, there is a perspectival assent by the viewer to be the monster and therefore be a voyeuristic accessory to the crime.

The film, according to this analysis, made us identify, and live vicariously through, the gang members as they rape, humiliate and kill the girls–this is done by the camera’s persistent focus on the terrified faces of the girls–and then as the gang members are hacked, chopped and killed by the “civilized” parents. For the audience to be truly affected by the narrative, they must identify with the monsters. When that identification takes place, there is a perspectival assent by the viewer to be the monster and therefore be a voyeuristic accessory to the crime.

I would make the case that this goes beyond just catharsis, but actually invites some form of transformation in the viewer from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde. This ultimately reveals ones own capacities for such thoughts and actions AND a strange, counterintuitive form of empathy and compassion for those “monsters” that fill the horror cinema landscape. In “New Horror,” everyone can occupy the space of victim and monster, occasionally in the same film.

Catharsis just allows for a person to have a safety valve to release fears, so they can then leave the darkened theater to laugh at those fears. There is no laughing when the credits roll on The Last House on the Left (and movies that follow it’s cinema verité approach). The audience is confronted and deeply affected by the dark depths of their own humanity. The feeling I always have with each viewing is acknowledgement, reflection on times in the past when I have wanted to be cruel or act on my need for vengeance and the ache of wanting to be cleansed of those thoughts and desires. And, also, the need for an actual shower.

There is no such miracle [like the redemptive ending of The Virgin Spring] at the end of The Last House on the Left. In a godless world without redemption, it includes no struggle with faith. Instead, the senseless evil inspires just more senseless evil, adding up to a nihilism that invites no happy endings (Zinoman, 79).

Horror then provides the reality check for its audience. It confronts them with something tangible, profound and troubling about the world, about others and, most significantly, about the very heart that beats in their chest and the very mind that forces order on an often chaotic, absurd and broken life. The church has lost its visceral prophetic edge (in the “truth-telling” sense) and no longer has the teeth to gnaw at the hearts and minds of its parishioners. Horror has found a way to take on the mantle that the church has failed at: confronting people with the bad news of human nature and the world. However, horror only exploits these truths for it’s own purposes. It’s central purpose is to get under the skin, expose fears and sins, not to provide a solution, a healing, for the existential turmoil.

Horror then provides the reality check for its audience. It confronts them with something tangible, profound and troubling about the world, about others and, most significantly, about the very heart that beats in their chest and the very mind that forces order on an often chaotic, absurd and broken life. The church has lost its visceral prophetic edge (in the “truth-telling” sense) and no longer has the teeth to gnaw at the hearts and minds of its parishioners. Horror has found a way to take on the mantle that the church has failed at: confronting people with the bad news of human nature and the world. However, horror only exploits these truths for it’s own purposes. It’s central purpose is to get under the skin, expose fears and sins, not to provide a solution, a healing, for the existential turmoil.

This is where the church, from the altars and the pulpits must then offer the balm, the salve, the grace and mercy of the cross as the response and answer to the truth of the reality with which horror confronts people. I am not entirely convinced the American church can find its prophetic edge again and steal back the reins from horror cinema (among other cultural products that do the same work), but, maybe, it can once again provide the sanctuary and grace–that it once was known for–to a people walking out of the new darkened temples where they are confronted by those oft-maligned films that fill the marquees spaces on most Friday nights.