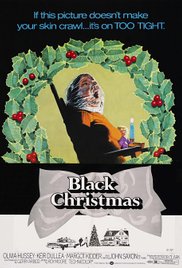

Before ‘The Shape’ ever stepped foot back in Haddonfield, Illinois and Jill Johnson was warned that the terrifying phone calls were coming from inside the house, there was ‘Billy,’ the perverted killer in the sorority house attic who wreaked terror in the days leading up to Christmas. Bob Clark’s 1974 classic, Black Christmas, is arguably the first actual modern slasher film which became largely obscured by the success and critical love of John Carpenter’s Halloween. Yet the simple and beautiful truth of Bob Clark’s film is that it accomplished the very things that other films have become more notable for including the first person, slasher villain tracking shots and the more effective use of the urban legend of the babysitter.

Before ‘The Shape’ ever stepped foot back in Haddonfield, Illinois and Jill Johnson was warned that the terrifying phone calls were coming from inside the house, there was ‘Billy,’ the perverted killer in the sorority house attic who wreaked terror in the days leading up to Christmas. Bob Clark’s 1974 classic, Black Christmas, is arguably the first actual modern slasher film which became largely obscured by the success and critical love of John Carpenter’s Halloween. Yet the simple and beautiful truth of Bob Clark’s film is that it accomplished the very things that other films have become more notable for including the first person, slasher villain tracking shots and the more effective use of the urban legend of the babysitter.

As the story goes, Black Christmas, at the time, was the highest grossing Canadian film. It didn’t get the same respect in the US, except for the attention of Carpenter himself who, as the story goes, asked Clark if he wanted to make a sequel to his film and he responded:

“No, I don’t intend to, I’m not here to make horror films, I’m using horror films to get myself established. If I was going to do one, though, I would do a movie a year later where the killer escapes from an asylum on Halloween, and I would call it ‘Halloween.’”

When both films are watched side by side, it becomes fairly easy to become less impressed with Carpenter’s creative prowess even though Halloween is more widely known and considered iconic American horror cinema. This isn’t necessarily to take away from Carpenter as a director as it is to raise Clark up as the creative impetus behind Halloween and, a year later, When A Stranger Calls—even though that film becomes more of a melodrama in its last half.

Black Christmas is one of those second-level, horror cinema deep cuts that looks deceptively cliché on this side of the 70s and 80s horror renaissance. It has all the traits of a true slasher film, but owes more to Italian giallo in how it builds atmosphere and tension. Most slasher films in their first cycle showcased a figure stalking prey over and over again. While Black Christmas utilizes this tactic at the beginning and in punctuated moments throughout the film, most of the suspense is built around phone calls to the young women in the sorority house. Billy, the slasher villain, gets his kicks by calling the girls from inside their house and speaking in hyper-sexualized and misogynistic monologues that sometimes include the screams of one of the girls he is about to murder. It’s a game of cat and mouse where the mice aren’t even cognizant that the cat is lurking in the very same space as they are.

Perhaps the most brutal element of the film is the master stroke of showcasing the suffocated body of the first sorority girl Billy kills, Clare, sitting in a rocking chair in the attic window unbeknownst to anyone. It is Clare’s disappearance that draws the attention of Clare’s father, the rest of the sorority and the cops and sets the murder spree and investigation in motion. All the while, the body of Clare sits by the attic window, mouth agape with a plastic bag over her head and lining the inside of her mouth. Billy is toying with them. He is hiding the key to his whereabouts in plain sight and is found rocking and talking to the dead Clare in a baby speak during the film. It is these touches that delineate Black Christmas from most slasher films and most Christmas horror.

Perhaps the most brutal element of the film is the master stroke of showcasing the suffocated body of the first sorority girl Billy kills, Clare, sitting in a rocking chair in the attic window unbeknownst to anyone. It is Clare’s disappearance that draws the attention of Clare’s father, the rest of the sorority and the cops and sets the murder spree and investigation in motion. All the while, the body of Clare sits by the attic window, mouth agape with a plastic bag over her head and lining the inside of her mouth. Billy is toying with them. He is hiding the key to his whereabouts in plain sight and is found rocking and talking to the dead Clare in a baby speak during the film. It is these touches that delineate Black Christmas from most slasher films and most Christmas horror.

However, the other reason I love Black Christmas—and a couple of other Christmas horror films—is its streak of meanness in the wake of what is considered a joyful, happy holiday. With holidays like Halloween and Valentine’s Day, there is already a hint of evil or naughtiness latched on to their surface meaning, but Christmas, in its truest form, is sacred to Christians because it denotes the birth of the God-man who came to save the human race from sin and death. It is good news of salvation. Even on a secular level, though, Christmas is considered, at its best, a time of joy, giving and peace. It seems counterintuitive, maybe, to turn those concepts on their head, but I think Black Christmas—and some of its descendants—is doing a great service to the holiday season.

Black Christmas gives us a reminder that Christmas’ existence is predicated on a world that isn’t right filled with people that are quite off in their desires and behavior. All of the murder and mayhem is leading up to Christmas in the film. We are not given complete resolution in the film, but the film is also not clear that we ever actually reached Christmas Day either. We as people in this world are stuck in the days leading up to the good news of Christmas—the perpetual second day between Good Friday and Easter morning to use another holiday analogy. Christmas is coming and it will come, but, in the meantime, we have to be cognizant of the reality: not everything is joyful, happy or peaceful, but it is the hope of the promise of those things that helps us survive.

Every year as we move into the season of Advent and Christmas day, it seems like gifts come with strings attached, the “war on Christmas” rallying cry for Christians rears its head again (even though the war was lost long ago) and we put more emphasis on the Santa mythos than we do the very person that even ol’ St. Nick beat heretics up for back in the good ol’ days—I think he was part of the “Greatest Generation” but don’t quote me on that. The point is Christmas has lost its bite, its cost, and its ability to shake us out of the complacency of our largely comfortable, consumeristic American life.

Every year as we move into the season of Advent and Christmas day, it seems like gifts come with strings attached, the “war on Christmas” rallying cry for Christians rears its head again (even though the war was lost long ago) and we put more emphasis on the Santa mythos than we do the very person that even ol’ St. Nick beat heretics up for back in the good ol’ days—I think he was part of the “Greatest Generation” but don’t quote me on that. The point is Christmas has lost its bite, its cost, and its ability to shake us out of the complacency of our largely comfortable, consumeristic American life.

The idea that salvation is predicated on something wrong, something bad, something, perhaps even, evil coming through the blinding sheets of snow on a cold winter’s night is provocative to me. It gives the actual meaning of Christmas, teeth. It gives the mind, the soul and the imagination something tangible to chew on instead of the sheer sentimentality of a big burly man leaving stuff under trees and eating cookies with milk or perceived religious persecution. No, I want a Christmas story that revels in the dark (droopy) underbelly of Santa Claus as he commits mass acts of breaking and entering. Christmas needs to gain its edge back.

And this is where a film like Black Christmas takes a step in the right direction. It reminds us Christmas is a holiday, a state of mind, even, that is juxtaposed against all of the ‘Billy’s in the attics of our life, threatening us and aiming to do us and others harm. If all the bad, evil things weren’t real, then there would be no need for Christmas. And everyone needs some Christmas in their life, even a Grinch like me.