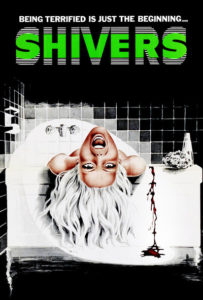

Shivers is a film about sex and parasitic worm-like creatures…and more sex. The film marks, both, the beginning of David Cronenberg’s feature directorial career and of the subgenre of horror called “body horror.” Body horror is driven by its exploration of and fascination with human flesh usually divorced from any transcendent meaning placed upon it by the philosophies or religions of humanity. Shivers nods respectfully to the sci-fi films of the 1950s where external, alien threats come to earth to change us. However, Cronenberg gives a scientific origin for the parasites that are rampaging through the modern apartment complex. Dr. Emil Hobbes has created the parasitic worms as a means to combat what he views as a humanity that is overly rationalistic and not in tune with their flesh or instincts.

Shivers is a film about sex and parasitic worm-like creatures…and more sex. The film marks, both, the beginning of David Cronenberg’s feature directorial career and of the subgenre of horror called “body horror.” Body horror is driven by its exploration of and fascination with human flesh usually divorced from any transcendent meaning placed upon it by the philosophies or religions of humanity. Shivers nods respectfully to the sci-fi films of the 1950s where external, alien threats come to earth to change us. However, Cronenberg gives a scientific origin for the parasites that are rampaging through the modern apartment complex. Dr. Emil Hobbes has created the parasitic worms as a means to combat what he views as a humanity that is overly rationalistic and not in tune with their flesh or instincts.

So the threat is made to be “natural” because it was created by the doctor as a kind of venereal aphrodisiac. However, Cronenberg does not have the threat “change” us like people were changed in The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Instead he makes the parasite amplify desires that are all too human. We are sexual beings that desire physical intimacy and connection. It is, especially in this day, a significant part of how we derive our identity and often shapes our political and cultural affections as well. But what happens when something causes us to lose our very humanity within an orgy of human flesh, bodily fluid and desire? This is the question that David Cronenberg explores in Shivers.

These parasites are transmitted through every form of sexual expression. They seek to bring human desires back to the realms of instinct and material, biological nature where no division can be made between the kingdoms of man and animal. They accomplish this feat by flattening humanity down to a singular facet: our sexuality. No longer is this just one aspect of our being; it is our being. It is who we are now; we are sex under the control of these parasites. Our bodies then become purveyors of parasitic survival: infect and spread or die. Our bodies become fleshy, streamlined mechanical carriers of biological terror. In other words, a good desire for physical intimacy becomes the only desire that drives our existence. We do not think, we do not feel, we do not care; we only screw without consent or mercy.

Our protagonist, Roger, the resident physician, happens upon Dr. Hobbes work and his plans to spread the parasite. Along with Nurse Forsythe, they spend most of the runtime of the film figuring out exactly what Dr. Hobbes’ intentions were, what the threat is and attempting to escape, but ultimately succumbing to the parasite. The final scene of the film finds Roger trapped in the apartment complex’s swimming pool as all of the residents enter into the pool, surrounding him, before Nurse Forsythe passes the parasite to him. The image is stark and finds its analogue within the act of sexual orgies, where multiple people are involved in drug and alcohol intake and unrestrained sexual activity with the rest of the group. Humanity is lost in the collective flesh, now nothing more than meat sacks with one drive and goal: go forth from this place and multiply.

There are absorbing Christian subtexts that careen through Cronenberg’s concept. On a very surface level, it could be said that sex separated from a spiritual underpinning becomes monstrous. While I think there is something to that very surface reading, I want to penetrate deeper into this tact. How does the spiritual element elevate sexuality? Within the Christian narrative, sex was designed as a good gift to humanity from God to enjoy and to create emotional and spiritual resonances between human creatures. The spiritual underpinnings explain the whys of human relationships and sexuality whereas the science (biology, psychology, etc.) explains what a thing is and how it works. Science can explain the mechanics of human sexuality but it struggles to explain the depths of emotions, human commitment and loyalty to a person and the existential depression in the midst of broken, intimate relationships.

A purely materialistic reading of human sexuality does not lend itself to internally derived morality or ethics. It lends to humanity viewing sex as nothing more than desire gratification, a gratification that needs to be satisfied regardless of the means. Only when there is an inherent value—for instance, the idea that every person is carrying the very image of God—in people can we make distinctions about proper ways to engage in sexual intimacy with other image bearers. Ultimately, Shivers makes a case that if everything is natural and there is nothing spiritual, nothing that transcends the materialistic explanations of science, then ethical concepts like consent become hard to derive and enforce. Shivers, I believe, makes the case, ultimately, that value cannot be derived from science. It must be given within the atmosphere of intimate, loving relationship.

A non-horror film that finds a similar parallel to Shivers in its argumentation is Steven McQueen’s 2011 film, Shame. In it, we see a relatively raw and accurate depiction of sex addiction. It’s protagonist, Brandon, attempts again and again to rid himself of his addiction and fails time and time again. The final scene shows Brandon giving in to the futility of ever being able to find relief and going out to experience a long night of various sexual activities. Like the final scene of Shivers, there is a scene where Brandon finds himself within an orgy of men, the culmination of the evening. In both films, these scenes depict sex that is cold, biological and detached from transcendent meaning and in both films the feeling that we are left with as viewers is one of a loss of humanity, a loss of uniqueness and nothing that could be described as love; all we sense is perfunctory sexual action.

While Cronenberg is not at all intending to make a case for religious transcendence, he does end up showing the deficits in the purely scientific and material understandings of sexuality and sexual acts. His interest in the horror of the flesh brings forth what one could call a negative theology: showing the problems and horrors of a world where transcendence does not happen and religion does not exist. If we see how materialistic explanations of sexuality (and other human behavior and action) fail to give a satisfactory explanation for our experiences then perhaps we will look towards religion, maybe even the Christian faith, for a more satisfactory answer.