When Alfred Hitchcock and the horror genre are mentioned in the same breath, the conversation is more than likely revolving around Psycho – Hitchcock’s 1960 classic that single-handedly evolved the horror genre into a new kind of monster. If Psycho isn’t the film being discussed, it’s usually the other side of the coin – 1963’s The Birds. Both films are horrifying and unnerving in their own ways, and both earn the wide praise they receive, especially in regards to how they benefitted the horror genre.

When Alfred Hitchcock and the horror genre are mentioned in the same breath, the conversation is more than likely revolving around Psycho – Hitchcock’s 1960 classic that single-handedly evolved the horror genre into a new kind of monster. If Psycho isn’t the film being discussed, it’s usually the other side of the coin – 1963’s The Birds. Both films are horrifying and unnerving in their own ways, and both earn the wide praise they receive, especially in regards to how they benefitted the horror genre.

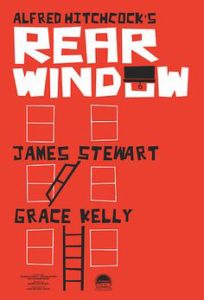

However, it could be the case Hitchcock’s most influential horror work came six years before Psycho in the form of an intimate, claustrophobic thriller called Rear Window. Released in 1954, it starred James Stewart as “Jeff,” a professional action photographer who broke his leg while photographing a racetrack incident. Confined to a wheelchair in his apartment during his recuperation period, Jeff can’t stop peering through his lenses into other people’s lives even while he’s not on the job. His newfound addiction concerns and frustrates his sophisticated and stunning girlfriend, Lisa (played by Grace Kelly). Jeff’s attention isn’t focused on the relationship he has inside his own room, but instead on the relationships displayed outside his own residence in full view.

Soon enough, one stormy night conjures the case of Jeff’s lifetime, as he hears a woman scream followed by the sound of breaking glass. Later on, he sees his neighbor, Thorwald, leaving the apartment he heard the noises coming from. As he continues to spy on Thorwald the following day, he spots more potential evidence of misconduct brandished in the bareness of the daylight hours, leading Jeff to suspect that Thorwald has murdered his wife. As the film continues, the circumstantial evidence begins to pile higher, as do the stakes of our main protagonists. They begin to run the risk of becoming the next victims while willingly inserting themselves into the story of the individuals they’re spying on.

In a day when our culture is constantly fighting to find the balance between individualism, self-expression, and the right to privacy, Rear Window has a lot to say. Not only do we have the blatant cautionary tale of how violating the private matters of strangers can come back to haunt us, it’s the alienation of Jeff from his own community that speaks the loudest lesson. Jeff clearly doesn’t know the people living in and around his apartment complex, more than likely due to the fact that he’s probably never at his residence because of his job. Instead of meeting and getting to know his neighbors’ names and personalities, Jeff sits in the shade of his apartment and delegates titles to them, such as “Miss Torso,” “Miss Lonelyhearts,” “Miss Hearing Aid,” and the “Newlyweds.” Jeff lives in a community, but he’s clearly not communing.

Unfortunately, we’re not all, unlike Jeff. How many of us really know our neighbors around us, whether we live in an apartment complex or in the middle of suburbia? How many of us really know the people we accept “friend requests” from or “follow” on social media sites, where those same people are able to see whatever information we release to our networks and profile pages? How many of us really know the people in the cubicles next to us at the office, or even the people who worship in nearby pews in our church congregations? All of these unknowns, and yet we still love to look out of our windows and peer into our neighbors’ yards or “stalk” someone’s Facebook wall, making judgments from afar while avoiding actual, in-person, physical interaction.

When one of Jeff’s neighbors experiences the death of her beloved dog, the following scene hammers truth into our guilty consciences. The owner shouts her grief into the commons area from her balcony, declaring, “You don’t know the meaning of the word ‘neighbors’! Neighbors like each other, speak to each other, care if anybody lives or dies! But none of you do!” All of the residents run to their windows to see what’s going on – except for Thorwald, who sits in the dark smoking a cigarette – but nobody goes to comfort the grieving woman. After she leaves her balcony, the residents of the complex immediately go back to what they were doing before. We all want to believe we’d be that person who comforts the woman, to weep with those who weep, but more often than not, we stay in our own rooms like Thorwald, watching or listening from a distance without risking oneself.

Maybe it’s this mentality that drives the popularity of one specific horror subgenre – the “found footage” category. Hitting the mainstream after the large success of The Blair Witch Project, “found footage” movies are filmed from a first-person perspective and follow the adventures, exploits, or tragedies of the cast of characters, giving the audience a sense of involvement and immediate connection. Modern horror classics such as Cloverfield have capitalized on this, and movies like Paranormal Activity, [REC]. and V/H/S have tapped into this segment of our psyche so well they spawned multiple successful sequels. Found footage horror films are still popular to this day because of the same things that lead to an amateur video of a terrible event going viral on YouTube: at our core, our curiosity consistently gets the best of us.

We see this happen in the climatic showdown between Jeff and Thorwald near the end of Rear Window. The “home invasion” horror subgenre seems to hatch out of its egg at this moment, burrowing itself into our subconscious fears. Jeff is faced with dire consequences for his spying and involvement in the spontaneous murder case, and when his secrets are finally discovered, we see him truly handicapped, naked before judgment. While we seem to have no problems peeping outside our windows at our neighbors, or viewing intimate videos and images of others’ lives, we’re absolutely scared to death when someone enters our own private domains. This, of course, is natural – privacy is important and a necessary part of life. But we have to admit our own contradictory views on the topic. For instance, certain people enjoy when a group of individuals leaks secret information about a political figure we dislike, but we get angry when the same group leaks information about a figure we trust and appreciate. We laugh when a friend tells an embarrassing anecdote about another friend, but become upset when that same friend tells an embarrassing detail about us. Why is this so?

If we’re made in the image of an all-knowing, all-seeing God, we shouldn’t be surprised when our need to know gets the best of us. After all, this is how sin entered the world, as told in Genesis 3. During His telling of the Parable of the Lamp, Jesus says to the crowd gathered around Him, “nothing is hidden that will not become evident, nor anything secret that will not be known and come to light.” (Luke 8:17) This is as true for others as it is for us, as God knows every detail about every being He has ever created. It is not our job to discover the truths about our neighbors outside our various kinds of windows, but it is our obligation to love them. Hiding in the dark to conceal their own acts did nothing to benefit Jeff or Thorwald, and we have no reason to believe it will do the same for us. Only by entering our communities with the light of Christ will we help others find the truth they crave.