Osgood Perkins (director of I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House and The Blackcoat’s Daughter) has done it again with his slow-burn retelling of this fairy tale. The structure of the story remains the same from the original Grimm’s Fairy Tale with a few changes and updates, a modern electronic score by R.O.B., and some gorgeous cinematography by Galo Olivares, one of the location cinematographers for 2018’s Roma. Perkins’ rendering has the quiet, natural landscapes of Terrence Malick mixed with the narrative ambiguity of Robert Eggers and laced with a dose of Panos Cosmatos’ psychedelia and madness. With this level of pedigree, it seems to be an utter stroke of luck that this is Perkins’ first mainstream film and perhaps his most accessible to date. Considering his other two films delve into haunted houses and possession, it makes sense that he would turn his attention to the stories that most children only know via the Disney-fied versions which strip them of much of their moral force. Picking one where children are in danger—and potentially eaten—is a risky endeavor, even for the goriest horror hound. Children in peril being a long-standing taboo in American cinema.

Osgood Perkins (director of I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House and The Blackcoat’s Daughter) has done it again with his slow-burn retelling of this fairy tale. The structure of the story remains the same from the original Grimm’s Fairy Tale with a few changes and updates, a modern electronic score by R.O.B., and some gorgeous cinematography by Galo Olivares, one of the location cinematographers for 2018’s Roma. Perkins’ rendering has the quiet, natural landscapes of Terrence Malick mixed with the narrative ambiguity of Robert Eggers and laced with a dose of Panos Cosmatos’ psychedelia and madness. With this level of pedigree, it seems to be an utter stroke of luck that this is Perkins’ first mainstream film and perhaps his most accessible to date. Considering his other two films delve into haunted houses and possession, it makes sense that he would turn his attention to the stories that most children only know via the Disney-fied versions which strip them of much of their moral force. Picking one where children are in danger—and potentially eaten—is a risky endeavor, even for the goriest horror hound. Children in peril being a long-standing taboo in American cinema.

Sophia Lillis (who played young Beverly in IT: Chapters 1 & 2) plays Gretel, the older sibling in this version, whose little brother, Hansel, becomes her charge due to a dead father and a mother—like in the original story—who is pressed by circumstances into forcing them out of the house in order to stay alive due to scarcity in the land and lack of work. She and Hansel wander into the woods, trip on shrooms—unknowingly, out of hunger—and happen upon a stark, triangular residence in the deep wood. Orange light glows from its windows. They look inside and find a veritable feast of meat, vegetables, cake, and baked goods laid out upon a grand table as if waiting for a party. The food beckoning to their starved stomachs, Hansel sneaks in and is caught in the midst of stealing food by the house’s lone resident, Holda (played by the wickedly brilliant Alice Krige). She invites them in, feeds them, houses them, and eventually recognizing this situation as better than starving in the woods, Gretel offers to do work around the house in exchange for food and shelter for them both.

What takes place should be of no surprise to anyone familiar with the original tale or with Perkins’ past films. This is not a “quiet-bang” kind of film. Perkins has never been interested in jolting his audiences, instead he wants to get past their sense of safety and let the dread of the tale linger with them after they have left the darkened room. There has not been a day since I watched this film (twice) that I have not thought about both its content and its gorgeous imagery as we follow Gretel reclaiming her own story, and the minefields all around that teeter on the edge of destroying her in the process. Much like the endings of The Witch and Midsommar, the seizing of power induces both relief and terror, freedom and its own form of slavery. And, also like those films, the point is not to ease that tension, but to force the audience to live in that tension, because those are the moments where cinema transcends into our metaphysical realities.

What takes place should be of no surprise to anyone familiar with the original tale or with Perkins’ past films. This is not a “quiet-bang” kind of film. Perkins has never been interested in jolting his audiences, instead he wants to get past their sense of safety and let the dread of the tale linger with them after they have left the darkened room. There has not been a day since I watched this film (twice) that I have not thought about both its content and its gorgeous imagery as we follow Gretel reclaiming her own story, and the minefields all around that teeter on the edge of destroying her in the process. Much like the endings of The Witch and Midsommar, the seizing of power induces both relief and terror, freedom and its own form of slavery. And, also like those films, the point is not to ease that tension, but to force the audience to live in that tension, because those are the moments where cinema transcends into our metaphysical realities.

Seeing Perkins wade out into the world of mainstream fare and nail it with all the confidence and style that he has brought to his independent features makes him an exciting director to watch for in the coming years. You can count on me being there on opening night for each one.

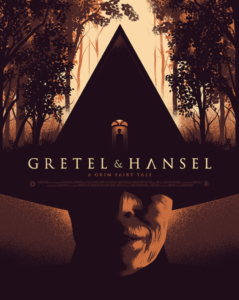

Review| Gretel & Hansel (2020)

Previous articleMy Top Ten 2019: David AtwellNext article "The End is the Beginning" - Star Trek: Picard S1E03