I, like all of you I’m sure, have fond memories of watching the Glee Holiday episodes. And, like everyone, only one thought spoiled all that holiday cheer for me: “I sure wish there were zombies in this episode.”

I, like all of you I’m sure, have fond memories of watching the Glee Holiday episodes. And, like everyone, only one thought spoiled all that holiday cheer for me: “I sure wish there were zombies in this episode.”

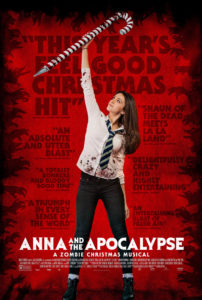

What’s better? Zac Efron in High School Musical? Or Zombie Zac Efron in High School Musical? Obviously, everything is better with zombies, and thanks to Anna and the Apocalypse, we can now add Christmas movies, high school movies and musicals to the list of genres that prove the point.

The titular Anna is navigating her final year of school, and she’s planning to take a year off to travel the world before heading to college. But before she can do that, the world ends with a zombie plague. But why is it set at Christmastime? Other than a shockingly lewd Santa song (performed at the school Christmas show, none-the-less) and Anna’s giant, zombie-slaying candy cane, this seems to be more a film that’s set at Christmastime than a film that embodies message of Christmas.

It’s true– Anna and the Apocalypse isn’t a particularly inspired Christmas movie. It functions much better as an Advent film.

Now that the Christmas season has consumed Thanksgiving and is eyeing Halloween while licking its lips, we mostly forget about Advent. Advent is the season of preparation for Christmas, marked by the four Sundays leading up to Christmas. It’s a season of fasting, prayer and repentance.

Advent is a season of apocalypse. The word ‘apocalypse’ comes to us from the Greek apokalypsis, which means ‘unveiling’ or ‘revelation.’ Apocalyptic books like John’s Revelation are called such not because they’re about the end of the world, but because they pull back the veil on reality, showing us the truth of things.

Advent invites us to return to a particular time in the story of God’s people—an apocalyptic time. Advent returns us to the centuries following the Exile, an apocalypse for God’s people in that the whole culture of Israel and Judah was destroyed. The political, religious and cultural life of God’s people was devastated and irrevocably changed. Those who lived through it talked about it as the End of All Things (read the poetry of Lamentations for a brutal, honest accounting of those days– the poet’s words wouldn’t sound out of place in a Walking Dead voiceover). What was revealed in the apocalypse of the Exile was the people’s continuing unfaithfulness to God and their covenant. They understood the Exile as the ripened fruit of the seeds sown by their faithlessness.

In the years after the Exile, they began to dream of a new world. They began to hope that one day a ruler might arise who would lead them faithfully.

This is the time we enter into during Advent. We remember the longing of God’s people for the Messiah, and we remember too that we are waiting for Jesus’ return.

Advent is a season of being caught between the way things are and the way they will be. Or, perhaps better said, between the way things seem to be and the way things really are. In other words, Advent is a season during which we long for apocalypse.

Anna’s story begins with longing. She’s about to face an everyday apocalypse: the end of high school. Her world feels small, constrained. She sings, in the song “Break Away:”

As I wake half dead in this same old bed

At the dawn of another day.

I feel chained and bound to this hopeless town,

And I know I must break away.

This sense of dissatisfaction with the way things are is where our Advent journey begins. We see the way things are, and we ache for something new. We have a sense that the way things are isn’t the way they should be. (We recognize those shortcomings in our own lives, too. Repentance is part of the Advent journey, so it’s not terribly surprising to find Anna and her friends singing a song called “Turning My Life Around,” either.)

One of the dark moments in the film comes when Anna and her friends are separated from their loved ones. There’s no cell phone service, and they have no way of knowing if anyone else is even alive. In the midst of this despair, they cry out for something more than the superficial connections our lives are filled with (connections the apocalypse has stripped away). Precisely because the apocalypse has stripped everything away from them, they recognize how alone they really are.

They sing:

I need a human voice,

Something that I can hold onto.

In all this static noise,

I need someone to break on through.

—”Human Voice”

Advent is an embodied season. We remember that Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us. Anna and her friends beg for an embodied voice—something beyond the “code and binary” we’ve become. That’s not unlike our cry, “O come, o come Emmanuel, and ransom captive Israel who mourns in lowly Exile here.” We remember that Jesus’ advent was embodied—the Word became flesh and came to live among us. We remember Jesus will return to us bodily, that God’s new kingdom will be here on Earth as it is in Heaven. And we remember that we are to be good news to the world, that our faith must be flesh and blood, that we are the “Human Voice,” the real, embodied connection those around us need.

Finally, Advent is a season of hope. We know the world is not as it will be. We know that, though love has the last word, we yet live in a world of scarcity. Many zombie stories chose this as the ‘reality’ they are revealing—this has long been The Walking Dead‘s purpose. The film seems to lean this way when one of the students trapped with Headmaster Savage (I see you, script) asks how they’ll care for the older people trapped with them. He grins and asks, “It’s the Zombie Apocalypse. What do we do?”

The student stammers, “Take care of each other?” to which he responds, “We prioritize.”

But he’s a clear villain, and the film is filled with moments of love, care and sacrifice in the face of certain doom. And as the few survivors pile into a car and drive into an uncertain future, Anna sings,

Where is the light that used to shine?

Oh, where is the life that once was mine?

But while there’s hope, while I still breathe,

I will believe.

—”I Will Believe”

This is not a Christmas moment. This is an Advent moment. It’s still night, and they have no proof the sun will rise. Israel had no proof God will remain faithful to God’s promises. We have no evidence Jesus will return to end injustice and oppression once and for all.

But as the preacher of Hebrews reminds us, “Faith is the reality of what we hope for, and the evidence of what we can’t see.” Advent is a season of faith. We light candles and trust that, as God has come before, so will God come again. We trust that no matter how dark the night, dawn is coming. We choose to hope. We choose to believe.

1 comment