You will no doubt hear the names Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman in any and every conversation about iconic 20th-century Scandinavian filmmakers—and rightfully so; perhaps someone will even mention Jan Troell or, more recently, the notorious Lars von Trier and his Dogme 95 movement. It is far less likely, however, that you’ll hear tell of Victor Sjöström—an almost-forgotten treasure of early Nordic cinema. In a way, it makes sense that Sjöström’s work as a director is all too frequently overlooked. He is most widely recognized as the actor who portrayed the protagonist in Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), and if he is recognized as a director, it is most likely for his 1921 film, The Phantom Carriage—his only work to receive a Criterion release (if that can be taken as a measure of cinematic acclaim).

You will no doubt hear the names Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman in any and every conversation about iconic 20th-century Scandinavian filmmakers—and rightfully so; perhaps someone will even mention Jan Troell or, more recently, the notorious Lars von Trier and his Dogme 95 movement. It is far less likely, however, that you’ll hear tell of Victor Sjöström—an almost-forgotten treasure of early Nordic cinema. In a way, it makes sense that Sjöström’s work as a director is all too frequently overlooked. He is most widely recognized as the actor who portrayed the protagonist in Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), and if he is recognized as a director, it is most likely for his 1921 film, The Phantom Carriage—his only work to receive a Criterion release (if that can be taken as a measure of cinematic acclaim).

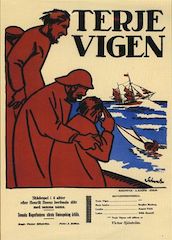

However, it is somewhat ironic that Sjöström should be so inextricably linked to Bergman in the collective public consciousness when, in fact, it was the former who so greatly influenced the latter (and not the other way around). “If we’re talking of those filmmakers whose work has really affected me and inspired me,” Bergman once said, “we have to begin with Victor Sjöström, him first and foremost.” In the end, Sjöström was a prolific director in his own right, one whose early work behind the camera helped usher in the first great age of continuity-driven narrative filmmaking. Given his status as an oft-overlooked master of early cinema, therefore, I suppose it is fitting, that I should write on one of his lesser-known films, Terje Vigen or, A Man There Was (1917).

Adapted from an eponymous poem by playwright Henrik Ibsen, Terje Vigen tells the story of a man—the titular Terje Vigen (who is played by Sjöström himself)—who, after living a life on the sea, settles down and has a family. He, his wife, and his young daughter live happily and harmoniously in the beautiful Norwegian countryside until the Napoleonic Wars reach their shores and a British blockade causes poverty and famine to spread throughout the land. In order to secure food for his family and friends, Terje hops in his boat and attempts to break through the blockade and sail to the neighboring country of Denmark. He is soon captured by a British captain who refuses to show him mercy, throwing him in prison instead. Some years later, after serving his sentence, Terje returns home and discovers that his family perished in the intervening time.

Enraged and driven to despair by this sad news, Terje Vigen isolates himself in his cabin by the seashore. One day a violent storm blows in. Terje spots a ship offshore, struggling in the maelstrom. An experienced seaman, he rushes out to help the family in trouble, but upon arrival, he discovers that the man is none other than the captain who put him in prison. So, Terje faces a dilemma: Should he exact vengeance, or grant the man and his family vengeance?

On a formal level, Terje Vigen—alongside a number of Sjöström’s other works, and the films of influential cinematic pioneers like D.W. Griffith—played a crucial role in establishing and concretizing conventions of continuity editing, as well as in challenging the then-contemporary tradition of theatrical framing devices and performances. Now the most widely used editing style, continuity editing attempts to hide the post-production process and create a seamless sense of cause-and-effect (usually linear) narrative progression, and this is precisely why continuity editing is sometimes referred to as invisible editing; the goal is to avoid drawing attention to the medium and means of production, thus moving the cinematic arts towards a kind of stylistic hyper-realism or naturalism.

And while many of the rules we associate with continuity editing practices—such as the shot/countershot convention and the 180-degree action rule—could not be invented until technology allowed for a more mobile camera, Sjöström’s post-production technique in Terje Vigen helped push mainstream, narrative filmmaking further in this direction. For example, in Terje Vigen, Sjöström utilizes a number of frame-edge cuts, in which a character’s exiting of the frame prompts a cut to a subsequent shot, where the character continues that action uninterrupted. Moreover—and again, in spite of the limited mobility of the camera in 1917—we see in this film the early stages of inside/out editing conventions. Consider an early scene in the film’s third act. Terje Vigen has learned that his family died, and he withdraws to his isolated seaside house. The opening shot of this sequence is very much an establishing shot. We see the exterior of the house, surrounded by the rocky shores. From there we move into the house and watch Vigen as he grieves his loss. By the scene’s end, we return back outside the house to see the ship caught in the intensifying storm. Today, this inside/out pattern is common practice; in 1917 it was a game-changer.

In addition to these editing conventions, Sjöström’s Terje Vigen marks a noticeable departure from the kind of theatricality that was customary—even necessary—in the early days of cinema. Here, Sjöström is content to let his characters move freely about the frame, creating a dynamic feel that is markedly different from the very staged look of many productions from the first decade of the 1900s. And even as a silent film, Terje Vigen relies less upon exaggerated physical performances and more on the nuanced action. Ultimately, film critic Bob Mastrangelo says it best: “The cinema allowed him [Sjöström] to draw on his years in the theater, but also opened up the possibilities the new medium offered.”

Terje Vigen is also indicative of the pioneering work of Victor Sjöström insofar as it showcases efforts to create films characterized more by psychological realism than fanciful melodrama. Indeed, Terje Vigen functions as a deeply personal meditation on suffering, grief, and revenge, with a little trans-national subtext thrown in for good measure. The apotheosis of the film is, of course, when Terje has the opportunity to kill the British captain who put him in prison. But he is moved to compassion when he sees the man’s young daughter, whom, it seems, reminds Terje of the child he lost. In the end, he spares the captain’s life, shows him mercy when he had received none. On one hand, this action is a perfect illustration of what a beautifully and wonderfully scandalous concept forgiveness is; and on the other hand, the fact that this act of grace transcends national boundaries in the era of the Napoleonic Wars, could be read through a more collectivist lens, implying that cultural, societal ills must be openly addressed if there is to be any hope for human flourishing. But to explore these themes any further would require another essay.

Terje Vigen is also indicative of the pioneering work of Victor Sjöström insofar as it showcases efforts to create films characterized more by psychological realism than fanciful melodrama. Indeed, Terje Vigen functions as a deeply personal meditation on suffering, grief, and revenge, with a little trans-national subtext thrown in for good measure. The apotheosis of the film is, of course, when Terje has the opportunity to kill the British captain who put him in prison. But he is moved to compassion when he sees the man’s young daughter, whom, it seems, reminds Terje of the child he lost. In the end, he spares the captain’s life, shows him mercy when he had received none. On one hand, this action is a perfect illustration of what a beautifully and wonderfully scandalous concept forgiveness is; and on the other hand, the fact that this act of grace transcends national boundaries in the era of the Napoleonic Wars, could be read through a more collectivist lens, implying that cultural, societal ills must be openly addressed if there is to be any hope for human flourishing. But to explore these themes any further would require another essay.

By the end of Terje Vigen, the titular character has died and lays buried alongside his family. The final shot of the film shows his grave, marked by a cross—a sign that Terje Vigen, as tumultuous as his life was, had received much grace indeed; and the very last intertitle of the film brings this motif home, telling us that Terje’s grave, much like his life, was surrounded by weeds, with wildflowers interspersed throughout. Perhaps, in part, that is what Sjöström’s sought to do in his films—point us to the flowers that grow among the weeds, to the opportunities we have to show and receive mercy and grace.