What are the factors and events that must happen in order to shift a person away from a violent and dangerous system of thought? Most of the answers given to this question are understandably abstract, because no singular process of actions work for each unique individual. So, instead, we say “love” or “resistance” or “protest” in order to give some description to these happy endings we read, watch, or hear. Guy Nattiv’s full-length treatment of his Oscar-winning short, Skin, gives us one such success story. Skin (2019) is based on the story of Bryon Widner and Daryle Lamont Jenkins.

What are the factors and events that must happen in order to shift a person away from a violent and dangerous system of thought? Most of the answers given to this question are understandably abstract, because no singular process of actions work for each unique individual. So, instead, we say “love” or “resistance” or “protest” in order to give some description to these happy endings we read, watch, or hear. Guy Nattiv’s full-length treatment of his Oscar-winning short, Skin, gives us one such success story. Skin (2019) is based on the story of Bryon Widner and Daryle Lamont Jenkins.

While the film doesn’t draw attention to this, Widner was, in reality, the co-founder of the Vinlanders Social Club: a white power group in Indiana which became one of the fastest growing racist skinhead groups in the nation. Where the real events and movie match up is in the events that led to Widner leaving the group and renouncing his white supremacist beliefs. This was due, in part, to meeting his wife—as well as her three children from another marriage—and becoming a father. The events shown in the film are rushed and scrambled compared to the real events. It was his wife, Julie, who ended up contacting Daryle Lamont Jenkins, the leader of One People’s Project and a black man, who ended up putting them in contact with the Southern Poverty Law Center in order to get Bryon’s tattoos—many of which were racist and violent in nature—removed.

The story that Nattiv tells, while inspirational, feels like the cinematic incarnation of an abstraction. “Love” turned him away from his former life and brought him to renouncing his former beliefs. Nattiv also gives Widner much more individual will in his film than it seems was the case in real life: in the film, he contacts Jenkins and comes to his decision to renounce his white supremacy beliefs largely on his own, except for a couple of small, inconsequential scenes where Julie and her kids refuse to take part in white supremacist actions. It seems that, in reality, the people who surrounded Bryon were much more active in moving him than the film would like to showcase.

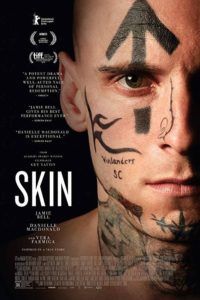

This isn’t to say that the movie isn’t effective in telling a story, even if it’s not the story. Deriving meaning from information is what filmmakers do when they are adapting a true story. Nattiv is clearly capable of constructing a solid film (one scene actually caught me so off guard that I literally jumped in my seat; this is not an easy thing to accomplish). Jamie Bell and Danielle MacDonald are stunning in their roles as Bryon and Julie. Bill Camp and Vera Farminga are appropriately creepy as the “parents” of the Vinlanders. Nattiv was able to get deeply effective characters out of his actors.

This isn’t to say that the movie isn’t effective in telling a story, even if it’s not the story. Deriving meaning from information is what filmmakers do when they are adapting a true story. Nattiv is clearly capable of constructing a solid film (one scene actually caught me so off guard that I literally jumped in my seat; this is not an easy thing to accomplish). Jamie Bell and Danielle MacDonald are stunning in their roles as Bryon and Julie. Bill Camp and Vera Farminga are appropriately creepy as the “parents” of the Vinlanders. Nattiv was able to get deeply effective characters out of his actors.

Probably my singular favorite moment happens in a conversation between Bryon, Julie and Daryle when Daryle gives him the news of a potential donor who would pay for his tattoo removals. Bryon (played with true conviction by Bell) asks relays his fear to Daryle: what if I am still “sh*tty” once all of these tattoos come off. This is the moment the film finally hits the central question at the crux of anti-racist work: once the trappings of a culture are taken away from an individual, can they be reformed or do the beliefs just go underground, in the subconscious?

I wish the whole of the film was able to really investigate this idea more. Instead, the story’s trajectory is a familiar one for an American audience: with a little help, we can will ourselves to be better people. Yet the truth is much more complicated and Widner’s battle was probably much more prolonged and excruciating. Daryle, Widner’s friend to this day, probably played a much more significant role that becomes rendered as not much more than a “magical negro” side story. Daryle lives to help white people get out of white supremacy. While this is courageous in its own right, Daryle must have had more complexities in the relationship to his mission than the film shows us. Even Julie’s storyline, while more central in the film, is much more passive in the spaces where she is trying to help Bryon move away from his former life and beliefs. Her concerns lie more with how he treats her children, having been burned before by men.

While Skin is more excusable in its storytelling and meaning-making than Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit was, it is still very clear that the story was told by a white, male filmmaker. A real life narrative that includes active players who are black and female take a back seat to the boot-strap theology of the white male who comes to these conclusions of his own will perhaps with a passive push by those on the outside. It is a story that white people can go see and feel good about themselves because we are not him. Yet he has successfully cleaned himself of all racism in thought and action by the end of the film, or so we conclude. This way we can assure ourselves that we are blameless of the more subtle, insidious incarnations of racism of which we are sometimes not aware of ourselves. We want our cake and eat it too. Seeing Nattiv’s rendition of this story allows us to visualize ourselves—those of us who are white—as being separate from (and also redeemed and free to ignore the sins of) our fathers, which we have been living with and off of in the years since.

While Skin is more excusable in its storytelling and meaning-making than Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit was, it is still very clear that the story was told by a white, male filmmaker. A real life narrative that includes active players who are black and female take a back seat to the boot-strap theology of the white male who comes to these conclusions of his own will perhaps with a passive push by those on the outside. It is a story that white people can go see and feel good about themselves because we are not him. Yet he has successfully cleaned himself of all racism in thought and action by the end of the film, or so we conclude. This way we can assure ourselves that we are blameless of the more subtle, insidious incarnations of racism of which we are sometimes not aware of ourselves. We want our cake and eat it too. Seeing Nattiv’s rendition of this story allows us to visualize ourselves—those of us who are white—as being separate from (and also redeemed and free to ignore the sins of) our fathers, which we have been living with and off of in the years since.

I would like to see this story from the perspective of a black filmmaker. I would like to see Daryle’s side of the story and see the complexities of his relationship with his work and his own battles with the sins of white people against his people. I would have liked to see Julie’s perspective be given more agency in the life of Bryon as well. I want to see what seems to be the true story: Bryon’s deliverance from white supremacy, instead of Bryon delivering himself from those spaces. We, as a society, need to see that when we are in an evil and dangerous mindset, it is the people around us who act in our favor. Our wills are too bound within the comfort of current belief systems. Perhaps cinematic portrayals of dependence on others are the true revolution that can lead to redemption.

• •

Guy Nattiv’s Skin can be seen In Theaters and On Demand July 26.