This piece was originally published on October 26, 2018 at Grindhouse Theology. With their permission, it is being republished here.

The concept of innocence is unusual coming from a Judeo-Christian viewpoint. Many branches of Protestant thought incorporate some formulation of sin where it affects, infects or enacts itself upon humanity from a very young age. A more Reformed tradition moves this infection to the very conception of a person. Something is broken from the very beginning. Selfishness is the operative disposition of the newborn. It is only concerned for its wants and needs; they show little to no concern for the exhaustion of their parents. Young childrens’ wont is to not share their toys or to become jealous at what other children possess. These are normal human behaviors. We have all been that kid. So, in this sense, we are not innocent. We are, to some extent, born with an innate unwillingness to put others first.

The concept of innocence is unusual coming from a Judeo-Christian viewpoint. Many branches of Protestant thought incorporate some formulation of sin where it affects, infects or enacts itself upon humanity from a very young age. A more Reformed tradition moves this infection to the very conception of a person. Something is broken from the very beginning. Selfishness is the operative disposition of the newborn. It is only concerned for its wants and needs; they show little to no concern for the exhaustion of their parents. Young childrens’ wont is to not share their toys or to become jealous at what other children possess. These are normal human behaviors. We have all been that kid. So, in this sense, we are not innocent. We are, to some extent, born with an innate unwillingness to put others first.

That, in and of itself, is not pretense for becoming a serial killer, a pedophile, or any other malcontent one’s mind wants to focus upon as model of sinful behavior, but it tracks a propensity that is inherent in our very being. If not nurtured or corrected through loving parenting, education, practiced empathy, etc., the propensity can become much more distorted and twisted within each of us. In this sense, innocence could be defined as a period of time when a child “doesn’t know any better” or has not reached a cognitive and self-aware maturity of self. Their sense of morality, ethics and practice have not been solidified—which happens at much younger ages than many of us would like to think. When we talk about the loss of innocence, we speak to that movement of the child from childhood to adulthood whether by natural progression through nurture or through events that are forced upon them: death, poverty, sickness, domestic/sexual abuse, or any number of external factors that act upon them.

Part of the human story—and a part that doesn’t get as much press in majority Christian culture—is that, not only are we born with an innate selfishness, but we are born into a world constructed by broken systems, culture, and influence that is created by a collective selfishness—or sinfulness—of humanity. No one is perfect and no act is purely private (or perfectly good), affecting only the one who acts. Our innate protection and elevation of self is going to lead to compromised communities which gives way to corrupted policies which then can lead to negative relations between peoples and nations to the point where even a person’s good acts can lead to bad outcomes. And, often, bad acts can raise a person to power and stature. The negation of the commonly held notion of “karma.”

Part of the human story—and a part that doesn’t get as much press in majority Christian culture—is that, not only are we born with an innate selfishness, but we are born into a world constructed by broken systems, culture, and influence that is created by a collective selfishness—or sinfulness—of humanity. No one is perfect and no act is purely private (or perfectly good), affecting only the one who acts. Our innate protection and elevation of self is going to lead to compromised communities which gives way to corrupted policies which then can lead to negative relations between peoples and nations to the point where even a person’s good acts can lead to bad outcomes. And, often, bad acts can raise a person to power and stature. The negation of the commonly held notion of “karma.”

Here is another part to the loss of innocence. It is the increasing knowledge of brokenness, immorality and evil in the world and the inevitable run-in with it on both small and large scales for each child. The cards are stacked against us when we come out of the womb. It is us versus the world AND us versus ourselves.

In 2017, I ventured upon a journey through the whole of the Halloween film franchise which as this year’s fantastic Halloweenies podcast has extolled is an endeavor of largely diminishing returns. Not only does the narrative trajectory become unnecessarily complicated, but keeping the timeline of the franchise straight would challenge the most creative minds. Even then, there are moments within the franchise—small as they may be—that work whether it was by design or by accident. My mind narrowed in specifically on Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers; a film so deeply marred by competing visions, last minute edits, and ill-guided homage that it has become a significantly maligned installment within the series. Leave it to a noted cynic and naysayer to say otherwise. But here goes nothing…

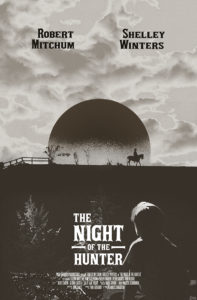

There was only one film that entered my mind as I watched Michael Myers stalk young Jamie—daughter of the first, second, seventh, and, now, eleventh film’s heroine, Laurie Strode—her friend, Billy, and a host of teenagers (as usual): The Night of the Hunter. The classic Southern noir starring Robert Mitchum and Shelley Winters was directed by Charles Laughton—his only film. In many ways, it is a perfect film. Simple setup: a con man, Harry Powell (Mitchum), finds out from a cell mate on death row that he has hidden money from a bank robbery and so, on release, Powell seeks to marry the man’s wife (Winters) and acquire the money for himself. The only thing that stands in his way are the woman’s kids who are the only ones who know where the money is hidden. Powell sets out to do whatever he must to get his hands on that money, including murder.

There was only one film that entered my mind as I watched Michael Myers stalk young Jamie—daughter of the first, second, seventh, and, now, eleventh film’s heroine, Laurie Strode—her friend, Billy, and a host of teenagers (as usual): The Night of the Hunter. The classic Southern noir starring Robert Mitchum and Shelley Winters was directed by Charles Laughton—his only film. In many ways, it is a perfect film. Simple setup: a con man, Harry Powell (Mitchum), finds out from a cell mate on death row that he has hidden money from a bank robbery and so, on release, Powell seeks to marry the man’s wife (Winters) and acquire the money for himself. The only thing that stands in his way are the woman’s kids who are the only ones who know where the money is hidden. Powell sets out to do whatever he must to get his hands on that money, including murder.

I am not here to make a case that Halloween 5 and The Night of the Hunter are congruent in quality. The latter is a masterpiece that truly remains in a league of its own, whereas the former is, honestly a bit of a slog to get through and is probably one of the most tonally inconsistent films in the franchise. However, I found the narratives of both films to be equally effective in how they address innocence within a world where active evil is a reality. In many ways Michael Myers and Harry Powell strike an equally immanent and terrifying force within their respective cinematic worlds. To the children who dare stand in opposition to them, they definitely appear to be an unstoppable force that will lurk and stalk and hunt until they get what they want.

In their own ways, Jamie, Billy, John, and Pearl are being forced to confront the discontinuity between their lack of maturity and knowledge about the world and an active force that intends to end them before they can overcome the growing pains from youth to adulthood. Evil, suffering and grief have a way of quickening these processes of human development. It is anything but fair. However, as Nietzsche stated famously, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.” The part that he conveniently forgot to elaborate on was the fact that it almost kills you. Lessons can’t be learned from and maturity can’t be attained if breath no longer inhabits our lungs. In both of these films, these innocent children are having to confront that simplistic and minimizing aphorism face to face.

In their own ways, Jamie, Billy, John, and Pearl are being forced to confront the discontinuity between their lack of maturity and knowledge about the world and an active force that intends to end them before they can overcome the growing pains from youth to adulthood. Evil, suffering and grief have a way of quickening these processes of human development. It is anything but fair. However, as Nietzsche stated famously, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.” The part that he conveniently forgot to elaborate on was the fact that it almost kills you. Lessons can’t be learned from and maturity can’t be attained if breath no longer inhabits our lungs. In both of these films, these innocent children are having to confront that simplistic and minimizing aphorism face to face.

This conflict is metaphorically realized in similar visual ways within the frames of each film. A young boy and a young girl being tracked through the woods with an imposing, often obscured, figure tracking them down in order to capture and probably kill them. The claustrophobia and ever-presence of the trees within the woods is a fitting way of presenting the trap that innocence finds itself in within a broken world. Recognition is inevitable. Maintaining innocence means they must keep running without noticing their surroundings. Constantly avoiding what is behind them, to the side of them; always focusing on what is before them: the clearing. The problem with keeping attention on the clearing in the distance is that one is less likely to be sure-footed. The trip, the trees from the side, or the imposing figure from behind drawing nearer will drag us into the cruel reality of the world in which we live. The clearing promises innocence, but we are doomed because the threats are too numerous and our sure-footedness is crippled. If they do finally reach the clearing, they will not be the same children they were when they first entered the wood. Something will have happened in between. The promise of innocence will have been nothing more than a mirage in the distance.

In this way, Michael Myers and Harry Powell are stand-ins for the inevitability and cruelty of maturity. Always chasing, never relenting, until the children are new creatures. There is a wisdom having come out of the woods. The troubles and brokenness have scratched and poked and torn into each of their bodies and souls. There is a forced sense of reality that broadens their world. They will recognize the threats, the trees, and…the change in themselves. Both what was before and what is now inform the person in the clearing. A self-awareness is brought about by the knowledge, trauma, suffering and self-realization they just went through.

In this way, Michael Myers and Harry Powell are stand-ins for the inevitability and cruelty of maturity. Always chasing, never relenting, until the children are new creatures. There is a wisdom having come out of the woods. The troubles and brokenness have scratched and poked and torn into each of their bodies and souls. There is a forced sense of reality that broadens their world. They will recognize the threats, the trees, and…the change in themselves. Both what was before and what is now inform the person in the clearing. A self-awareness is brought about by the knowledge, trauma, suffering and self-realization they just went through.

That clearing outside the woods never actually was innocence in the first place, but, upon arrival, we see its true state: maturation. Innocence promises safety because of its inherent blissful ignorance. Maturation, however, means growth. The new creature stands with the knowledge that Myers is still following in his 1967 Camaro and Powell is tracking on his reliable horse while singing “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” The scars from the trees are still present as a reminder of the past and what has already been experienced. The threats are still all around, yet we have learned from our enemy, from the past. The new creature has a minute amount of control, but the type of fear is different. It’s not a fear born of isolation, but a fear born from our forebears eating of the fruit in a long ago garden. The creature knows themselves better and, with that understanding, they have a visceral sense of the world around them, the circadian rhythm of woods and the clearings ahead.

Where John and Pearl have the advantage over Jamie and Billy is they were able to reach their clearing with the help of someone who had already been through many woods in her own life: Rachel Cooper. The Night of the Hunter over and against Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myersgives an image of how innocence can be lovingly guided into maturity. This is not keeping them from the threats, pain, and suffering, but loving them in the midst of the reality of the internal and external worlds they inhabit. And, if needed, fending off the Powells and Myers with a shotgun if they come in too hot.

Where John and Pearl have the advantage over Jamie and Billy is they were able to reach their clearing with the help of someone who had already been through many woods in her own life: Rachel Cooper. The Night of the Hunter over and against Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myersgives an image of how innocence can be lovingly guided into maturity. This is not keeping them from the threats, pain, and suffering, but loving them in the midst of the reality of the internal and external worlds they inhabit. And, if needed, fending off the Powells and Myers with a shotgun if they come in too hot.