After a decade of increasing social, political, and cultural unrest around the world, the seventies found Hollywood shifting into the structural norms that we currently recognize and are beginning to push back against in our current era. The Civil Rights movement, the beginning of the Vietnam war, the introduction of feminism and freer models of sexuality, among other significant events made the cinematic ground fertile for a new class of filmmakers and studios to come into their own.

After a decade of increasing social, political, and cultural unrest around the world, the seventies found Hollywood shifting into the structural norms that we currently recognize and are beginning to push back against in our current era. The Civil Rights movement, the beginning of the Vietnam war, the introduction of feminism and freer models of sexuality, among other significant events made the cinematic ground fertile for a new class of filmmakers and studios to come into their own.

The Hays Code died out and was eventually replaced by the MPAA; however, during the seventies, film code was largely relaxed and allowed filmmakers to explore elements of cinema that had largely been too taboo or sensual to be displayed on the big screen. Sex, drug use, violence, and alternate lifestyles became normal in the American film industry as the tides were turning from the old studio and filmmaking models to a younger group of industry leaders and directors.

Like we talked about in the 1940s, Hollywood’s relationship with the American government began to be tested as the Vietnam War came to its ambiguous conclusion in ‘75. This conflict was the first war in America that was generally viewed poorly; to the point that returning soldiers were treated with indifference at best, and disrespect and violence at worst. The seventies exemplified the Hollywood that sought to challenge the vision of the American Dream and the government’s foreign and domestic policies. No more were the days when Hollywood would willingly and freely serve the propagandistic needs of its political leaders. By the end of the decade, directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Michael Cimino were beginning to envision the ambiguity and frustration that the American people had felt around Vietnam. Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter would begin the cinematic scolding of American intervention in Vietnam which would only become more frequent in the subsequent decade.

Like we talked about in the 1940s, Hollywood’s relationship with the American government began to be tested as the Vietnam War came to its ambiguous conclusion in ‘75. This conflict was the first war in America that was generally viewed poorly; to the point that returning soldiers were treated with indifference at best, and disrespect and violence at worst. The seventies exemplified the Hollywood that sought to challenge the vision of the American Dream and the government’s foreign and domestic policies. No more were the days when Hollywood would willingly and freely serve the propagandistic needs of its political leaders. By the end of the decade, directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Michael Cimino were beginning to envision the ambiguity and frustration that the American people had felt around Vietnam. Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter would begin the cinematic scolding of American intervention in Vietnam which would only become more frequent in the subsequent decade.

Along with films tackling civil unrest and challenging the myth of American exceptionalism, underground, exploitation, and cult films began to see the light of day. With the development of home video technologies such as the VHS tape (created in Japan in 1976) and the first paid premium station (HBO, in 1972), the way cinema would be consumed expanded. People could pay for premium content that did not have to fall under television codes. These premium stations were able to up the ante when it came to the quality of their programming, which brought in more viewers, and in turn created more profit to make the programming better, and so on. Home video created the possibility to see movies whenever one pleased much more easily, instead of possibly never being able to see a film again after it left the theaters. How people viewed film, between the start of the home video age and new premium stations, would shift the landscape and redefine the possibilities for Hollywood’s profit system moving forward. Much of the technology that began in the 70s would hit its peak in the 80s, something we’ll discuss next month.

The style of Hollywood films changed considerably during the decade as the “New Wave” of filmmakers began to saturate the market. Directors like John Carpenter, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma, Peter Bogdanovich, and many others would become the new pioneers of modern cinema. While they were given opportunities and unbridled creative power to make the films as they visualized them, many of these directors were cognizant of the directors and filmmakers that laid the foundation before them—sometimes to the point of being critically scolded for being rip-offs, as with DePalma and Hitchcock. Yet there is a rawness to the stories being told by this new crop of visionaries, as if the Lord was raising up prophets forged out of a frustrating, difficult, and turbulent couple of decades in order to present cinematic visions that would turn the mirror onto its audience and this country and interrogate the social, cultural, political, and economic health of this nation. Few films probably did this as successfully as horror did beginning in the 1970s. The seventies set up the framework in which the monsters and aliens and gothic mansions of the 30s, 40s, and on, became more palpable, realistic, and visceral. And, in many occasions, gross.

The style of Hollywood films changed considerably during the decade as the “New Wave” of filmmakers began to saturate the market. Directors like John Carpenter, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma, Peter Bogdanovich, and many others would become the new pioneers of modern cinema. While they were given opportunities and unbridled creative power to make the films as they visualized them, many of these directors were cognizant of the directors and filmmakers that laid the foundation before them—sometimes to the point of being critically scolded for being rip-offs, as with DePalma and Hitchcock. Yet there is a rawness to the stories being told by this new crop of visionaries, as if the Lord was raising up prophets forged out of a frustrating, difficult, and turbulent couple of decades in order to present cinematic visions that would turn the mirror onto its audience and this country and interrogate the social, cultural, political, and economic health of this nation. Few films probably did this as successfully as horror did beginning in the 1970s. The seventies set up the framework in which the monsters and aliens and gothic mansions of the 30s, 40s, and on, became more palpable, realistic, and visceral. And, in many occasions, gross.

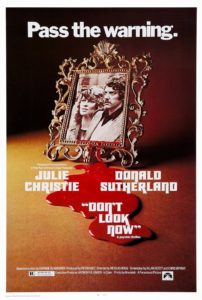

Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now has come into its own reappraisal in the last five to ten years, specifically within the keeps of “Film Twitter.” Unlike some horror in the 70s, there is merely a haze, or suggestion, of the supernatural that lingers along its plot line instead of full-fledged assault—like The Exorcist, which came out the same year. Don’t Look Now strikes more chords with the gothic macabre films of Hammer or classic ghost stories like The Innocents or The Haunting. Its intent is to suffocate its audience with the weight of loss and grief. And in its final act we see that a smaller thread running through the film intersects with the main thrust of the film and all comes undone.

Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now has come into its own reappraisal in the last five to ten years, specifically within the keeps of “Film Twitter.” Unlike some horror in the 70s, there is merely a haze, or suggestion, of the supernatural that lingers along its plot line instead of full-fledged assault—like The Exorcist, which came out the same year. Don’t Look Now strikes more chords with the gothic macabre films of Hammer or classic ghost stories like The Innocents or The Haunting. Its intent is to suffocate its audience with the weight of loss and grief. And in its final act we see that a smaller thread running through the film intersects with the main thrust of the film and all comes undone.

Our main characters are played by a young Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, a couple we are introduced to at what is to become the lowest point in their marriage: their daughter drowns in a freak accident behind their house. We are then transported to Venice, Italy, sometime after her death, where John Baxter (Sutherland) is working to renovate a church and Laura (Christie) has joined him on the project. Their son, meanwhile, is at a boarding school in England. While it doesn’t necessarily show on their faces, the film places cues throughout that act as brief reminders of their loss and in those spaces the audience knows this is a haunted couple attempting to cling to whatever they can to survive. As we see their daily lives go forward, the film largely sidelines, yet strangely keeps up with a series of murders that have been taking place in the city.

Enter two mysterious sisters—one of whom is blind and has psychic abilities—who somewhat awkwardly enter into the lives of the this grieving married couple to announce that the psychic sister has seen their daughter, she is happy, and wants them not to grieve any longer. Laura at first is distraught and initially passes out only to recover and, according to John, be reinvigorated with life as if nothing ever happened. She wants to go into church to say a prayer, and we are shown an intimate sexual encounter between the two that is full of passion and vigor that audience is led to believe had not happened in a while. She has been given second life. John, on the other hand, remains haunted and only devolves more when he starts witnessing what appears to be a child in a small red slicker running around the city, the same red slicker his daughter died in.

Enter two mysterious sisters—one of whom is blind and has psychic abilities—who somewhat awkwardly enter into the lives of the this grieving married couple to announce that the psychic sister has seen their daughter, she is happy, and wants them not to grieve any longer. Laura at first is distraught and initially passes out only to recover and, according to John, be reinvigorated with life as if nothing ever happened. She wants to go into church to say a prayer, and we are shown an intimate sexual encounter between the two that is full of passion and vigor that audience is led to believe had not happened in a while. She has been given second life. John, on the other hand, remains haunted and only devolves more when he starts witnessing what appears to be a child in a small red slicker running around the city, the same red slicker his daughter died in.

While the end of this film ties all of these threads together into a devastating (but truly rewarding) blow, it’s this persistent meditation on grief that strikes such a profound note throughout the film. Laura figuratively dies and comes to life again when she passes out, after receiving the news of her daughter being happy wherever she is on the other side of the veil. John does not see any of these psychic visions from the blind sister and therefore does not believe the sister has a connection beyond the material world, but that their daughter is truly dead and that she does not live on beyond the grave. We find the couple brought asunder by what could be seen as a matter of faith: Laura’s faith in life beyond death brought to her as a distressing moment of revelation is its own form of conversion. From belief in a body decaying in the worm-inhabited ground to resurrection beyond the material world she can sense. Yet John remains in the grief of loss and his inability to save his daughter. That inability and guilt ultimately keeps him from the same faith as his wife experiences. He can’t forgive himself, and faith means believing that our actions don’t bring about redemption.

Anyone who has fought through the grief of losing someone knows that feeling of guilt or regret that accompanies the death of a loved one. Grieving the life of someone is good, and should be leaned into and be allowed to take place on its own time; but when the focus becomes that lingering guilt or regret and the person hardens in that space of being unforgiven, the descent to hopelessness and the death of the soul is nigh. Don’t Look Now becomes a haunting reflection on the cost of grief and how faith in something beyond the material can break the shadowy veil we find ourselves draped in.

Anyone who has fought through the grief of losing someone knows that feeling of guilt or regret that accompanies the death of a loved one. Grieving the life of someone is good, and should be leaned into and be allowed to take place on its own time; but when the focus becomes that lingering guilt or regret and the person hardens in that space of being unforgiven, the descent to hopelessness and the death of the soul is nigh. Don’t Look Now becomes a haunting reflection on the cost of grief and how faith in something beyond the material can break the shadowy veil we find ourselves draped in.