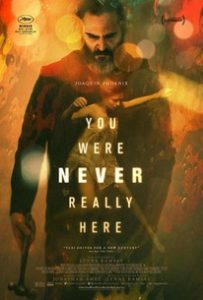

Early in Lynne Ramsay’s Cannes-winning, You Were Never Really Here, Joaquin Phoenix’s Joe returns home from a job to find his mother unmoving in front of the TV. Knowing what we know of Joe, we’re not sure if his mother is sleeping, drugged up, or dead, maybe even killed by Joe’s own hand. As he draws near, a classic movie playing loudly from a TV possibly gifted to Joe’s mother when he was born, she breaks into a smile and the two of them share a laugh. She off-handedly quips Psycho was on TV. Later the next morning, Joe, in frustration over his mother taking too long in the bathroom, he imitates the shower scene murder from the aforementioned Hitchcock classic.

Early in Lynne Ramsay’s Cannes-winning, You Were Never Really Here, Joaquin Phoenix’s Joe returns home from a job to find his mother unmoving in front of the TV. Knowing what we know of Joe, we’re not sure if his mother is sleeping, drugged up, or dead, maybe even killed by Joe’s own hand. As he draws near, a classic movie playing loudly from a TV possibly gifted to Joe’s mother when he was born, she breaks into a smile and the two of them share a laugh. She off-handedly quips Psycho was on TV. Later the next morning, Joe, in frustration over his mother taking too long in the bathroom, he imitates the shower scene murder from the aforementioned Hitchcock classic.

An innocuous bit of playful fun between mother and son cuts to the core of Joe and the true guts of Ramsay’s film. A traumatized war veteran troubled with memories of war and an also hinted at abusive childhood, Joe lives teetering on the edge of coming undone. The only anchor tethering his existence is the affectionate bond between him and his mother. Like any mother/son relationship, especially with an aging mother, he cares for her and even stresses over her expired food in the fridge while she fusses over his long-past relationships and his mysterious keeping him out late at night.

Little does his mother know his past experiences have shaped him into a violent, dispassionate man capable of brutal violence. However, his trusty weapon of choice, a ball-peen hammer, is not used to take out unsuspecting targets, but to rescue kidnapped children. Unlike his cinematic counterpart from Psycho, Norman Bates, Joe’s relationship with his mother and traumatic past has not led him to violence against women but led him on a vicious, back alley street to redemption.

Yet, his choice of profession does not remain a level path. After accepting a job to rescue a senator’s daughter, Nadia, and successfully completing the mission, those attached to the job begin to be brutally murdered. Hints of a deeper conspiracy involving the governor begin to surface. What results is a total loss of control and a disorienting barrage of swift retribution leaving Joe seemingly hopeless. Like another cinematic New York war vet, Travis Bickle, Joe is left feeling like Bickle’s famous line, “Loneliness has followed me my whole life, everywhere. In bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores, everywhere. There’s no escape. I’m God’s, lonely man.”

The way Ramsay films the city streets capture Joe’s traumatic headspace and adds to the film’s tension. There is very little spatial awareness given as the camera does nothing to establish place or geography. Ramsay’s movie is hectic and never gives you a sense of space or geography and establishes New York as claustrophobic, downtrodden, yet electric. Likewise. Johnny Greenwood’s score quick jabs and pounds like a hammer, Joe’s weapon of choice. It wobbles and skips with undulating synth and drums as Joe world falls apart and the violence grows in intensity. A score like this hasn’t created uneasiness and set the mood for a movie since Mica Levi’s in Under the Skin.

For as much as this movie is in Joe’s head, Scorsese’s mercurial protagonist from Taxi Driver may be the nearest correlation to him. Like Bickle, Joe reaches a psychological breaking point threatening his fragile mental state. Yet, when the pivotal moment arrives for both of them, they choose to live for the sake of another, in De Niro’s character it’s Jodi Foster’s underage sex-worker and for Phoenix’s character, it’s Nadia, the aforementioned senator’s daughter. However, while De Niro’s Bickle ends up channeling his acerbic, hate-filled need for control by “cleaning up the streets”, Joe lives to fight to save a version of himself and his mother. It is clear both he and his mother suffered abuse at the hands of possibly his father, and he tracks down Nadia to attempt to overcome the traumatic demons inside himself and hopefully spare the girl the same fate.

Despite both protagonists achieving similar goals by the end of their respective stories, both Travis Bickle and Joe are stand-ins for a crisis point in their time. Bickle embodying the fragile state of masculinity in America in the 1970’s: isolated, alone, slowly losing control of a country and system once male-dominated. Joe, likewise, embodies a modern masculinity; further anchored to only fragile support systems–something veterans have become all-too-familiar with–and desperately grasping at a way forward to find a way in an increasingly isolated and toxic world. Nadia’s captivity is a seemingly fitting way for Joe to find redemption in making a violent end of the twisted male captor and rescuing a young girl from his perverted bondage. However, where you expect him to “John Wick” the big bad and dispose of him in an incredibly violent way, this redemption is, literally and figuratively, cut off.

The abrupt suspension of a typically satisfying revenge/redemption killing is a fitting development borne out of careful, cinematic choices made throughout the film. There is, without question, savage and bloody violence, but it is portrayed in a detached and brutal manner to show violence for what it really is: inhuman and awful. Few movies I can remember make violence something the audience can repute while still empathizing with the hero. The climax of the movie undercuts this further by making the most violent and visceral death of the movie unseen, disquieting, and subversive.

The final moments of Ramsay’s film posit a complementary solution to the problem of controlling, toxic behavior leading one man to a sick, lethal fascination with his murdered mother and another to a small moment of human connection resulting in violence and the spilling of his own blood. The hardest thing to do when power has led to corruption is to let go of the need to solve the problem and approach it with humility and admission of our own powerlessness to change it. Phoenix’s Joe exemplifies a better way by finding his own redemption in the meek yet powerful frame of the young Nadia. Perhaps our best way forward is the hope of humbly realizing our need for one another and the expectant declaration that today, “is a beautiful day.”

This review is from Josh’s coverage of the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival in Madison, Wisconsin. You can find out more about the festival by going to 2018.wifilmfest.org.