David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) still stands as an example of cinema that succeeds at balancing the visceral thrills and exploitation of true crime narratives with a sensitivity towards those victims, investigators, and involved bystanders who actually lived in the Zodiac’s shadow. Fincher vies for splatters of blood on windshields, muzzle flashes from a detached distance, and victims faces in the midst of mostly implied violence to accomplish the film’s dread. Yet, it remains a very human story. One that immerses the audience in the emotional sinews and suffocation that filled the air around San Francisco during the 1970s. Somehow Fincher and his superb cast are able to turn this true (and still officially unsolved) tale of a serial killer into one of the most stark and remarkable crime noir/crime procedural films of the new century.

David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) still stands as an example of cinema that succeeds at balancing the visceral thrills and exploitation of true crime narratives with a sensitivity towards those victims, investigators, and involved bystanders who actually lived in the Zodiac’s shadow. Fincher vies for splatters of blood on windshields, muzzle flashes from a detached distance, and victims faces in the midst of mostly implied violence to accomplish the film’s dread. Yet, it remains a very human story. One that immerses the audience in the emotional sinews and suffocation that filled the air around San Francisco during the 1970s. Somehow Fincher and his superb cast are able to turn this true (and still officially unsolved) tale of a serial killer into one of the most stark and remarkable crime noir/crime procedural films of the new century.

Horror breathes deep within the damp, darkened mists that roll over the varied elevations and streets that merge into focus on a bridge that crosses the watery abyss. Horror works best when it refuses to indulge the human desire to make sense, rationalize and control the unknown. The Zodiac case is a cold case, one that continues to breed new theories to this very day. The details of the case and the lack of conclusive evidence ends up accomplishing, in real life, what horror films try to do on the flickering screen. Fincher utilizes this in the very foundations of his world-building.

Two specific scenes showcase the film’s ability to cull out horror within the seeming banality of everyday people. The first scene happens halfway through the film when we have already been introduced to the crimes, paranoia, and media frenzy which the Zodiac killer had wrought. A young woman drives down a darkened interstate with her baby in the passenger seat and is flagged down by a man, whose face is obscured, claiming her car’s tire is loose. He offers to tighten it, but ends up loosening it more so she will be resigned to accept his offer of a ride to a gas station. Fincher plays this moment like another potential crime scene for the Zodiac.

As soon as the man drives past the gas station, we share in the uneasy terror of the lady as she recognizes what is really going on. Our fears are warranted when he states he will toss the baby out of the window before he kills her. The scene fades before we are brought to the highway, once again, where the young woman is found frightened and frenzied by two fellow travelers on the highway. The dread hangs heavily over the scene: did he actually throw the baby out of the car even though he was unsuccessful in killing the woman?

As soon as the man drives past the gas station, we share in the uneasy terror of the lady as she recognizes what is really going on. Our fears are warranted when he states he will toss the baby out of the window before he kills her. The scene fades before we are brought to the highway, once again, where the young woman is found frightened and frenzied by two fellow travelers on the highway. The dread hangs heavily over the scene: did he actually throw the baby out of the car even though he was unsuccessful in killing the woman?

The woman frantically moves to the ditch. The viewer clutches the seat, perhaps expecting a small mangled body. Just then, a whine. A cry that signifies a respite of hope in the midst of utter, true terror.

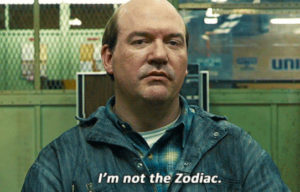

The second scene revolves around the film’s protagonist, Robert Graysmith (played by Jake Gyllenhaal)–the cartoonist turned obsessed amateur sleuth and the audience’s surrogate for most of the film—who runs down a potential break in the case at the house of a man who had information on Rick Marshall, the suspect Graysmith was investigating. The man, Bob Vaughn, worked at the movie theater along with Rick Marshall. Graysmith asks Mr. Vaughn about the movie posters which contained the handwriting closest to what experts thought was the handwriting of the Zodiac. Mr. Vaughn says that it was not Rick’s handwriting, but, in fact, his own. Graysmith’s face becomes pale and suffocating atmosphere we have grown accustomed to has returned. The man asks if he wants him to check the records in the basement to see if the film, The Most Dangerous Game (1932), had played at that theater in 1969. Graysmith hesitantly follows him into the basement.

A creak is heard overhead. Rhythmic footfalls on worn wooden floors. Graysmith asks if anyone else lives there with no response. The creaks continue and the tension is getting worse. The man finds the proper book with the record and he tells Graysmith that it played 9 weeks before the first Zodiac murder. Graysmith, distracted by the noises, asks again if someone else lived there and the man answers, “Would you like to go upstairs and check?” The possibility that he might be in the den of the Zodiac makes him start toward the stairs only to find the front door locked. The man follows him through the basement, turning out the lights as he goes, up the stairs and eventually unlocks the door. Graysmith leaves. Nothing happens. The paranoia of the Zodiac infusing itself into spaces that may not even contain his presence.

A creak is heard overhead. Rhythmic footfalls on worn wooden floors. Graysmith asks if anyone else lives there with no response. The creaks continue and the tension is getting worse. The man finds the proper book with the record and he tells Graysmith that it played 9 weeks before the first Zodiac murder. Graysmith, distracted by the noises, asks again if someone else lived there and the man answers, “Would you like to go upstairs and check?” The possibility that he might be in the den of the Zodiac makes him start toward the stairs only to find the front door locked. The man follows him through the basement, turning out the lights as he goes, up the stairs and eventually unlocks the door. Graysmith leaves. Nothing happens. The paranoia of the Zodiac infusing itself into spaces that may not even contain his presence.

It is not the scenes by themselves that get under the skin, but their implications that give conceptual heft to film. Both of these scenes are misdirecting. They have little to no direct involvement in the case Graysmith is making against the man he is finally convinced is the Zodiac.

The man driving on the lonely highway, threatening the woman and her child is not the Zodiac. Neither is the man who brings Graysmith into his musty basement. These scenes are intentionally placed within the narrative of the film to give a real sense of systemic human evil. The film’s main protagonists are blindly concerned with the Zodiac. They are obsessed to the point of nearly destroying their lives and reputations. However, it is these minor vignettes placed in the film that tell us something significant about our obsession with true crime narratives. Serial killers do not exist within a vacuum, they exist in a space where other evil, sinister works of man take place, simultaneously, with only a red thread of sin and violence to connect them.

The lie we tell ourselves is as long as we are not in the presence of the Zodiac then we will be safe. We are fascinated with these cases because it allows us to contain and control these monstrous acts as human anomalies. However, as these scenes show, evil permeates societies, cities, towns, families, etc., biding its time before it rears its head. Most of them never become media obsessions and true crime sensations, they happen under the radar. They happen when our eyes are on the celebrity killer—the public scapegoat—letting our strong sense of the true nature of humanity soften.

The lie we tell ourselves is as long as we are not in the presence of the Zodiac then we will be safe. We are fascinated with these cases because it allows us to contain and control these monstrous acts as human anomalies. However, as these scenes show, evil permeates societies, cities, towns, families, etc., biding its time before it rears its head. Most of them never become media obsessions and true crime sensations, they happen under the radar. They happen when our eyes are on the celebrity killer—the public scapegoat—letting our strong sense of the true nature of humanity soften.

Serial killers are as human as anybody. They come from a specific town or city, a specific neighborhood, a specific house, and specific parents. They are someone’s next door neighbor, friend, lover, coworker, etc. They are ubiquitous to society until they become the new fascination of the media, their blood-stained hands displayed publicly. To understand them as something other than wholly human is to fool ourselves, given any number of circumstances and contexts, that someone we know—or even ourselves—could never become the next Zodiac. Transgression runs like a formidable stream deep beneath the crust of our society’s psyche.

Anyone could become the next Zodiac. We’ll never be rid of the serial killer. As soon as one is caught and/or killed, another (or two) will rise in his or her place. Evil is relentless in this world. It will always be with us. This is the dark reality that permeates Zodiac and the world around us. It’s not the most hopeful note to end on, but a sober note to reflect on.