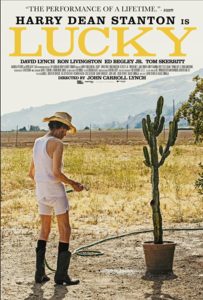

Veteran actor John Carroll Lynch’s directorial debut, Lucky (2017), is a simple, wry, and subtly affecting film that is unafraid to ask big questions about life, death, grief, and acceptance. Lucky is also the perfect swan song for the late Harry Dean Stanton, who plays the film’s titular protagonist—a cantankerous, aging atheist nearing the end of his life, searching for solace.

Veteran actor John Carroll Lynch’s directorial debut, Lucky (2017), is a simple, wry, and subtly affecting film that is unafraid to ask big questions about life, death, grief, and acceptance. Lucky is also the perfect swan song for the late Harry Dean Stanton, who plays the film’s titular protagonist—a cantankerous, aging atheist nearing the end of his life, searching for solace.

Lucky wakes up every morning, performs the same five yoga exercises, and slowly rambles through the dusty streets of the small town he calls home. Eventually he makes his way to the local diner, where he superficially gabs with the waiter. He wanders on over to the convenience store to buy his daily pack of cigarettes, and eventually he heads to the bar and chats with his friend Howard (David Lynch), who is distressed by the fact that his pet tortoise has run away from home. (In spite of its melancholy heart, Lucky is a tremendously funny film.)

Lucky’s ritualistic life is mirrored in the film’s narrative structure, and so we are inscribed into Lucky’s story, made to sympathize with him by experiencing his loneliness and isolation firsthand. John Lynch’s camera, with its dingy yellow-tinged compositions, makes Lucky’s torment our own; moreover, his camera never strays far from our unhappy protagonist, and the closeup work catches all of Harry Dean Stanton’s weathered, world-weariness. And Stantons performance, which could very well earn him a posthumous Oscar, likewise elicits our sympathies from start to finish. There is a delicious gruffness and cold indifference in his vocal delivery, to be sure, but Stanton is at his best here when he is silent, staring off into the distance, or taking a long draw on his cigarette, or kicking a can down the street. His work here is truly with the price of admission in and of itself.

But I suppose what ultimately sets Lucky apart from the scores and scores of “grumpy old man” films out there is its refusal to fully submit itself to the vapidly saccharine conclusion the genre so often demands. Yes, the film does have Lucky making a transition from a grumpy atheist to slightly-less-grumpy-athiest, thanks to the help his friends and fellow townsfolk, but there is very little room for victory or celebration in Lucky’s change of heart. After all, his final conclusion that all one can do in the face of the vast incomprehensibility of the universe—the endless void, as he puts it—is smile, is far from a triumphalist perspective. In the end, that Lucky is unwilling to function as cinematic comfort food—as a sort of Facing the Giants for atheists—is what makes it so worthwhile. It’s the kind of film best viewed, discussed, and digested with friends of different backgrounds and beliefs, for Lucky, in all its deceptively simple garb, is a film that understands how imperceptibly small we humans are on a cosmic scale. “There are some things in this universe, ladies and gentlemen, that are bigger than all of us,” Lucky’s friend Howard shouts to his friends in the town bar, “and a tortoise is one of them.” Or, as the Preacher said, “Go to the ant, you sluggard!”