A couple of months ago, my review of Detroit opined the failure to keep the eyes of the audience on the black narrative and, instead, found it’s gaze concentrated on the white Detroit police officers at the center of the film’s torturous central set piece. My hesitation going into my viewing of Marshall was palpable. I was concerned that, like Detroit, the story of Thurgood Marshall would find its focus within a white gaze, specifically in showing Marshall as a man whose character attributes would be acceptable by white standards of respectability. It’s very easy for white filmmakers to find their interpretation of Civil Rights leaders like Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King, Jr. within an assumption that the unity King spoke about has come to fruition. However, the news headlines, day after day, tell us a different story, one that implies continued struggle and protest and suffering for the African American community. White filmmakers seem to want the culmination of the Civil Rights Movement’s hope without doing any of the hard work and soul-searching required. They take these films and parade them around as if racism is past tense and defeated as an American scourge. Hence why most of them center their story on American unity instead of the struggle and continued oppression inherent to blackness in America.

A couple of months ago, my review of Detroit opined the failure to keep the eyes of the audience on the black narrative and, instead, found it’s gaze concentrated on the white Detroit police officers at the center of the film’s torturous central set piece. My hesitation going into my viewing of Marshall was palpable. I was concerned that, like Detroit, the story of Thurgood Marshall would find its focus within a white gaze, specifically in showing Marshall as a man whose character attributes would be acceptable by white standards of respectability. It’s very easy for white filmmakers to find their interpretation of Civil Rights leaders like Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King, Jr. within an assumption that the unity King spoke about has come to fruition. However, the news headlines, day after day, tell us a different story, one that implies continued struggle and protest and suffering for the African American community. White filmmakers seem to want the culmination of the Civil Rights Movement’s hope without doing any of the hard work and soul-searching required. They take these films and parade them around as if racism is past tense and defeated as an American scourge. Hence why most of them center their story on American unity instead of the struggle and continued oppression inherent to blackness in America.

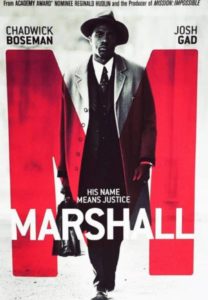

However, with the arrival of Ava DuVernay’s Selma and, now, Hudlin’s Marshall, it feels like we are starting to see a glimmer of what it takes to tell good black stories: having black people tell them. Unlike DuVernay, Reginald Hudlin–who has worked almost exclusively in TV for that last fifteen years–doesn’t have the hype behind his name. His last films were critically-panned comedies, Serving Sara, The Great White Hype, and the highly underrated SNL-spinoff film, The Ladies Man. Nothing about his filmography makes this a safe choice for a historical biopic of the first African American Supreme Court Justice. Not to mention the fact that the film revolves around one of the cases that defined his career, a case where he relies on a white Jewish insurance lawyer to be his voice when a judge denies him the role of lead defense attorney and places him in contempt of the court if he speaks during the trial. The simple fact that this film does not immediately give itself over to the white gaze is a huge credit to Hudlin’s direction, primarily, and Michael and Jacob Koskoff’s script, secondarily.

There is no question that this film is about Marshall’s victory in the trial by the end of the film. Josh Gad’s Sam Friedman becomes emboldened and forsakes his earlier concerns about his reputation by the end of the film, but there is not a question in anyone’s mind who actually won the court case. If Thurgood Marshall had not been there every step of the way then Friedman would have taken a deal or passed the case on to someone else. The very act of Sam being the mouthpiece for Marshall in this court case feels like a subtle jab at the continual appropriation of black culture and thought by white people. The whole case breaks on the words that Thurgood has Sam say. There is potential commentary here on the success of white people often coming from the sweat of the black community. This reading was maybe not have been intended within the scope of the film, but whenever we look at civil rights narratives, sometimes imagery can take on meaning beyond initial intent.

Chadwick Boseman plays Marshall with enough swagger and self-assuredness to buck up against the potential white-washing of his role. He is defiant and violent against those white townspeople who try to silence him and degrade him with racial slurs. He has no problem being cheeky to his white counterparts and flat out flaunting his refusal to give in to white authority when his client’s life is on the line. The most telling thing about the depiction of Thurgood Marshall within the scope of the film is how deep the cost of his legal veracity is when it comes to his family, the potential funding of the NAACP and his very life and limb. The threats come from inside and outside the courthouse and they just keep coming, taking different forms around every corner. And Marshall stares these threats down with a smirk on his face.

Hudlin’s direction is able to maintain a black gaze on the cinematic world of Thurgood Marshall without demeaning Sam Friedman’s ethnicity. What makes this more than just the typical white-guy-who-meets-black-man-and-hesistantly-becomes-woke narrative is that Jews were not viewed as “white” either, but as a minority to be derided and subjected to a second-class citizenry. Marshall and Friedman had a shared central value: neither were considered within the ranks of “truly American.” Whenever progressive thinkers talk about intersectionality, part of that concern is how to address the oppression of various groups without minimizing any of their unique concerns or creating a hierarchy of importance within the pursuit of civil rights. The beauty of the film is how it, subtly, attempts to envision what that might have looked like in this specific story. They were able to see each other for who they were through their shared suffering.

There is a scene in the restroom after they have both been beaten by white supremacists who despised their collective defense of their client who was charged with raping and attempting to murder a white socialite. They are getting ready for the court case and Marshall turns to Friedman and tells him that “you’re one of us now. You’re a fighter.” Two men with two different lives and sets of struggles, both demeaned in their own ways by their country, see themselves in each other. This is what makes them successful in their case, ultimately, but, more importantly, this is why the film works so well: we see that at the bottom of technical terms like intersectionality is something more human: empathy for others. If we can feel the other’s pain, viscerally, then we can begin to hear them and see them and then fight for them. This is a deeper unity than nationalism or patriotism, this unity is based on an ancient concept that our creation has one source, one image.

The fact that Marshall is able to accomplish such a dynamic film within a relatively straightforward biopic formula says a lot about how minority directors will always be able to tell their own stories with the most nuance and accuracy, avoiding the whitewashing of cinematic worlds and the revisionist history of Civil Rights heroes by the white, majority narrative. I can only hope that Marshall doesn’t end up on the pile of underrated and forgotten films while films like Detroit only continue the narrative that we, white people, cling so tightly to in order to wash our hands of our peoples’ (and country’s) sins.