“Whatever exists, [the judge] said. Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” – Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West

“There’s imagery there. The religious text is great mythology. Out of that mythology you can draw great stories, and in the same way we talk about Icarus flying so high to the sun, we know it’s not true, but we learn so much from it. There’s a lot to get out of them. These are the oldest stories of humankind, that three major religions are based on.” – Darren Aronofsky, ‘mother!’: Darren Aronofsky Answers All Your Burning Questions About the Film’s Shocking Twist and Meanings

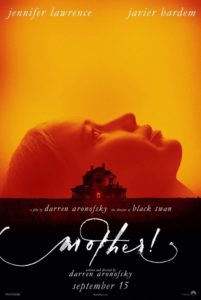

mother! has done its work. It has provoked its viewers into opposing sides: those who were offended by its outlandishness and ‘shocking’ imagery and those who have come to its defense as a film that dared to do something different in a land of remakes, reboots, cinematic universes, and cash-grabs. Both sides have a point and it is easy to see what they each get right. mother! is not a film that can be classified with Letterboxd ratings and simple “I like it” or “I hate it” superlatives. It demands more of its audience. It wants to draw viewers in and then make them pay for it. Aronofsky appropriates religious imagery and narrative to speak on political and sociological ills and then undercut those religious claims to truth in extra-textual interviews like the one above. The film lives in aesthetic ambiguity, transcending mere declarations of “masterpiece” and “pretentious flop.” To Aronofsky’s credit, this may be the film’s strongest attribute: a speechless response.

mother! has done its work. It has provoked its viewers into opposing sides: those who were offended by its outlandishness and ‘shocking’ imagery and those who have come to its defense as a film that dared to do something different in a land of remakes, reboots, cinematic universes, and cash-grabs. Both sides have a point and it is easy to see what they each get right. mother! is not a film that can be classified with Letterboxd ratings and simple “I like it” or “I hate it” superlatives. It demands more of its audience. It wants to draw viewers in and then make them pay for it. Aronofsky appropriates religious imagery and narrative to speak on political and sociological ills and then undercut those religious claims to truth in extra-textual interviews like the one above. The film lives in aesthetic ambiguity, transcending mere declarations of “masterpiece” and “pretentious flop.” To Aronofsky’s credit, this may be the film’s strongest attribute: a speechless response.

The film is set in an Edenic rural house that is set apart from the rest of the world. Mother (played by Jennifer Lawrence) is the caretaker and maintainer of the home. Her husband, Him (played by Javier Bardem) is a poet, a creator of rhythm and word. They are both shapers of worlds. While Aronofsky has come out and said that Mother is a cinematic representation of Gaia—the Greek primordial goddess of all life, Mother Earth—Mother’s character could also be seen as the Holy Spirit in community with the God-like Him. Eden, Spirit, God, shapers of word and worlds. Sound familiar? At this point, the audience should have an idea where the film is headed. The Fall (featuring two greats, Ed Harris and Michelle Pfeiffer as bit-player Adam and Eves), fratricide, prophets, zealots (one played by underrated actor, Stephen McHattie), drunken orgies, a flood, evangelism and an apocalypse. The film moves through the narrative scope of the Bible in two hours and fifteen minutes. It includes the quick, but violent death of Ricky Bobby’s favorite 8-pound, 6-ounce newborn infant Jesus—something that many found to be a little too much for the screen—played with the dark comedy-tinged flippancy of a Life of Brian set piece.

The scope of Aronofsky’s vision is really quite impressive and something that should truly be praised. However, the most frustrating aspect of the film is how every beautiful element that it contains is saddled with a pretense or a flippancy that offsets it. Mother is constantly confused and frustrated by her husband’s unwillingness to turn away their increasing numbers of visitors. His reasoning shows a reckless grace that is often, from a human perspective, a consistent characteristic of God’s love for the world. It’s rather beautiful even though the cost of that reckless grace seems to be a destruction of sorts; the violent bearing it away to use the old Biblical terminology. Yet, at the same time, this depiction of God is problematic because he keeps stating over and over again that these creatures, these visitors, are what give him the inspiration to get past his writer’s block. Thereby loosening the touchpoints between Him and the traditional Christian characteristics of God in which God lives in the perfect community of the Trinity and has infinite creativity from which to work. He simply does not need humanity to “inspire” Him.

The scope of Aronofsky’s vision is really quite impressive and something that should truly be praised. However, the most frustrating aspect of the film is how every beautiful element that it contains is saddled with a pretense or a flippancy that offsets it. Mother is constantly confused and frustrated by her husband’s unwillingness to turn away their increasing numbers of visitors. His reasoning shows a reckless grace that is often, from a human perspective, a consistent characteristic of God’s love for the world. It’s rather beautiful even though the cost of that reckless grace seems to be a destruction of sorts; the violent bearing it away to use the old Biblical terminology. Yet, at the same time, this depiction of God is problematic because he keeps stating over and over again that these creatures, these visitors, are what give him the inspiration to get past his writer’s block. Thereby loosening the touchpoints between Him and the traditional Christian characteristics of God in which God lives in the perfect community of the Trinity and has infinite creativity from which to work. He simply does not need humanity to “inspire” Him.

It is Aronofsky’s consistent pressing against boundaries of religious orthodoxy—because he probably did not present reincarnation and Greek mythology with perfect exactness either— that is refreshing in giving an alternative rendering of these religious narratives, yet runs into similar problems as other religious films have had. Whenever an artist utilizes belief systems and doesn’t actually see them as intimate and personal systems of truth that real people throughout history have based their understanding of the world on and is how they get through this difficult life, the imagery loses some of its power. It’s a subtle, but real, disrespect towards peoples’ beliefs in the name of inclusivity and social cohesion to appropriate them without rendering them with some fairness.

This is notable in part in the scene with the death of the messianic child takes place, it feels anticlimactic. It feels like it has changed nothing. It has done nothing to turn the tide. It feels like another cog in the piecemeal machinery that Aronofsky has built. Normally, this would not be a significant thing if his strong use of the Judeo-Christian narrative, up to that point, had not been so on the nose. When that act happens in the Biblical narrative, the world is flipped and history and time is severed and everything changes. In this film, it felt needless and of no consequence except to make Mother give in to violent retributive justice. Which feeds nicely into the feminist critique of male dominance in society, but ultimately the strands of metaphor and allegory begin to unravel from their already fragile tapestry. The cohesion of these strands must be more natural instead of coerced for the allegory and commentary to line up into a moving and meaningful vision. The strands are interesting in and of themselves, but for them to actually come together would have been truly powerful.

It is still a film that needs to be experienced even with these critiques. The film plays like an intimate, single-setting version of the Biblical epics in the days of old. It is something that will not be seen elsewhere. It’s a welcome entry into what, sometimes, feels like a stale slate of Hollywood fare these days. However, don’t come out of the film feeling like you must proclaim a passionate love or hatred for it. It’s okay to just not know. Matter of fact, that may be the most telling thing about the film: it defies human ability to categorize it. It is art. It is there to challenge, convolute and confound us. To make us think about it and about ourselves and about our beliefs. mother! achieves this end and, really, that’s all we can ask from a film.

as usual, great writing Blake. This is a very complicated movie to have a simple opinion on…. but in short i think this is a spectacular artistic and commercial failure. i have never been so bored, so annoyed and so “over” a film while watching it…. and yet….. and yet…. there is a germ of something good. i might be biased, but i believe the two “germs” of goodness is A} the source material B} the visual style. – but in the end my feeling could be summed up in the thought i had half way through this film: “man i wish i was watching Noah again, this is dreadful”