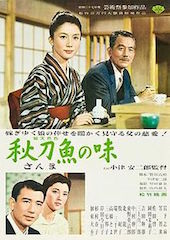

Director Yasujiro Ozu may not be as well-known in the West as Akira Kurosawa – easily the most recognizable name in classic Japanese filmmaking – but his role in not only shaping the cinema of his own nation but also the history of the entire medium cannot be overstated. Those at least somewhat familiar with international cinema have probably heard of Ozu’s Tokyo Story as it rightfully and frequently appears on “greatest films ever” lists and possibly his earlier masterpiece Late Spring as well. But, from a career that produced over fifty films over the course of nearly fifty years that influenced countless filmmakers as distinct as Abbas Kiarostami, Jim Jarmusch, Claire Denis, and Wes Anderson, one might expect greatness outside just two signature films. And, if a curious cinephile were to probe much further into the director’s mighty canon, he or she would quickly stumble upon An Autumn Afternoon.

Director Yasujiro Ozu may not be as well-known in the West as Akira Kurosawa – easily the most recognizable name in classic Japanese filmmaking – but his role in not only shaping the cinema of his own nation but also the history of the entire medium cannot be overstated. Those at least somewhat familiar with international cinema have probably heard of Ozu’s Tokyo Story as it rightfully and frequently appears on “greatest films ever” lists and possibly his earlier masterpiece Late Spring as well. But, from a career that produced over fifty films over the course of nearly fifty years that influenced countless filmmakers as distinct as Abbas Kiarostami, Jim Jarmusch, Claire Denis, and Wes Anderson, one might expect greatness outside just two signature films. And, if a curious cinephile were to probe much further into the director’s mighty canon, he or she would quickly stumble upon An Autumn Afternoon.

Next to Tokyo Story and Late Spring, Ozu’s final film serves as another obvious highlight in a career of so many. It features many of the director’s characteristics – floor-level camera angles, meticulously staged framing, familial and generational concerns set against the backdrop of a post-WWII Japan – and even reworks the central father-daughter relationship of Late Spring for its primary concern. An Autumn Afternoon, then, serves as a fitting swansong for one of the medium’s greatest masters. If viewers ever level a complaint against Ozu, it’s that his films are far too similar in theme and execution to possibly offer anything new with each subsequent release. To put it mildly, I find this reading of his work, unfortunately, dismissive. His films may not provide the thrills of Kurosawa’s samurai epics, but it’s undeniable that they are meaningful art and great thematic depth in the director’s similarly constructed works.

His final film is no exception. Throughout An Autumn Afternoon, Ozu’s camera captures a rapidly changing Japan in painterly fashion as it marvels at the hallmarks of modernity – boisterous baseball stadiums, red-striped smoke stacks, sleek high rises, bright neon signs. It’s remarkable how much beauty Ozu can glean from the ugliness of industrialization. It’s gorgeous, geometric compositions comprised almost entirely of static shots are like onscreen moving portraits. Too, the film wonderfully underscores the collision of East and West in a postwar Japan as businessmen in suits and ties sit cross-legged on the floor to eat, or as women alternate between kimonos and pencil skirts depending on the occasion, or as family members and friends, old and young, must grapple with shifting norms as the rest of the world threatens to leave behind those beholden to tradition.

It is from within this tension that Ozu unearths his story. Aging widower Shuhei Hirayama is a successful war veteran who has three adult children, two of which still live under his roof. As his loving daughter Michiko approaches her mid-twenties, he begins facing unexpected pressure from friends and colleagues to quickly marry her off before it’s too late. Though neither father nor daughter has any desire to rush the young woman into marriage – a decision likely to forever alter their close bond – the power of tradition compels this family’s patriarch to pursue the matter further. While Late Spring heart-achingly explored the same conundrum from the perspective of the daughter, An Autumn Afternoon primarily focuses on Shuhei and his own internal struggle as a parent.

The situation becomes more complicated when Shuhei and his old school pals run into a former teacher of theirs who reveals that he mistakenly never encouraged his own daughter to marry. Now, with his respectable teaching days behind him, the man lives a lonely life running a modest noodle shop with his forlorn middle-aged daughter. Meanwhile, Michiko’s older brother Koichi encounters his own struggles in marriage as he and his wife Akiko don’t see eye to eye on many things. Together, these simple stories paint a compelling and affecting portrait of the generational changes all families must face. Too, the film offers several weighty themes for its viewers to mull over despite its bouncing, carnivalesque music score. The film causes us to contemplate how the rise of modernity has also intensified materialism. It encourages us to witness the shadow of a great war that still looms over a nation with unknown lasting effects. And, it challenges us to determine for ourselves what of tradition is worth clinging to and what is acceptable to let go of with the passing of time.

Yasujiro Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon is not likely a film for everyone. It moves along at a gentle, careful pace and leaves most of the story’s major events off-screen. But, in doing so, it most certainly offers a welcome alternative to standard Hollywood fare for those looking for something a little different. It’s a film that refreshingly favors inference over exposition. For instance, in its final act when Michiko prepares for her wedding, Ozu chooses not to show us the ceremony or celebration and instead cuts to a series of shots of the family’s empty house. Though Michiko’s marriage is likely to bring her and her family a lot of future happiness, Ozu forces us to meditate on all of the other emotions that also come with such a major life change. This, then, is the appeal of the wondrously subtle, wholly unique filmmaking of one of the cinema’s greatest directors.