The internet and its wave of social media platforms have provided a new breeding ground for documentaries. When information about everything is available with a click at any time, questions of interpersonal communication, ethics, privacy, among other concerns present themselves for investigation. There are endless angles to take when looking at social media. The common argument—often by generations that did not grow up with the sharp incline of technology—is that young people are always looking at their phones and they miss the world and people around them. While there is plenty of surface observational material to support this accusation, the statement does not deal with how whole generations are affected by significant technological shifts. We are already starting to see a backlash starting within the same generation against the isolation of our online lives.

The internet and its wave of social media platforms have provided a new breeding ground for documentaries. When information about everything is available with a click at any time, questions of interpersonal communication, ethics, privacy, among other concerns present themselves for investigation. There are endless angles to take when looking at social media. The common argument—often by generations that did not grow up with the sharp incline of technology—is that young people are always looking at their phones and they miss the world and people around them. While there is plenty of surface observational material to support this accusation, the statement does not deal with how whole generations are affected by significant technological shifts. We are already starting to see a backlash starting within the same generation against the isolation of our online lives.

However, history shows us a significant shift in communal relations when another significant technological invention came on the scene, something we actively take for granted now: the television. There is historical evidence that shows how neighborhood relations, outdoor childhood play, and other facets of American life were drastically shifted with the arrival of the TV. I can imagine older generations making similar statements directing the blame onto younger generations, about how they were shifting socially in a potentially regressive way. Yet the actual question that probably should be dealt with seldom receives attention: How do quick technological shifts change the relational and psychological elements of life? Instead, we’d rather not deal with that question and find someone to blame.

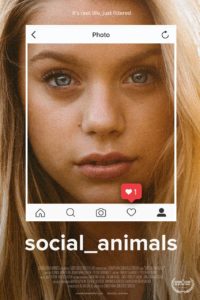

Social Animals, by Jonathan Ignatius Green, chooses to look at the actual effect of social media on three teens from differing backgrounds and socio-economic climes. Green is smart to focus in on one platform, not to mention the most popular one currently: Instagram. We are invited into the lives of upper class white girl Kaylyn Slevin, middle-westerner white girl Emma Crockett, and a black male NYC teen—who appears to be from a lower socio-economic standing—Humza Deas. As the documentary shifts from one story to the another, we begin to piece together how the race for popularity and social status changes the psychology of the teens, and actual real-world consequences to their signing onto the social platform.

Emma’s tale easily steals the show because the backlash and vitriol that is thrown at her Instagram account actually has life-and-death consequences for her midwestern life. Yet all of them deal with some aspect of internet life that has become prevalent: Kaylyn’s objectification and advances online by men—often significantly older—and Humza’s rise to Instagram fame and the backlash and claims that he is selling out or betraying the urban exploration communities he got his start in. As someone who just recently deleted most of his social media accounts, including Instagram, there are elements of these stories that make a lot of sense and only piled onto my initial reason for largely unplugging: weariness. The main theme I took away from the documentary was probably unintended: social media is utterly exhausting. Each of the characters is inundated with photographic representations of how their lives don’t live up; how they aren’t skinny, famous, or pretty enough; and how they are damned if they do and damned if they don’t gain notoriety. I was tired just watching these teens struggle with these issues.

Emma’s tale easily steals the show because the backlash and vitriol that is thrown at her Instagram account actually has life-and-death consequences for her midwestern life. Yet all of them deal with some aspect of internet life that has become prevalent: Kaylyn’s objectification and advances online by men—often significantly older—and Humza’s rise to Instagram fame and the backlash and claims that he is selling out or betraying the urban exploration communities he got his start in. As someone who just recently deleted most of his social media accounts, including Instagram, there are elements of these stories that make a lot of sense and only piled onto my initial reason for largely unplugging: weariness. The main theme I took away from the documentary was probably unintended: social media is utterly exhausting. Each of the characters is inundated with photographic representations of how their lives don’t live up; how they aren’t skinny, famous, or pretty enough; and how they are damned if they do and damned if they don’t gain notoriety. I was tired just watching these teens struggle with these issues.

So on this existential level, the documentary works. However, there was another underlying feeling that I was never quite able to shake throughout the documentary’s runtime: that none of what was shown—as bad as it was in some cases—was ever actually analyzed. When the teens are interviewed by the filmmakers, I’m not entirely sure the right questions were asked. I don’t expect them to have these fully formulated thoughts that reveal a detached awareness of their being (after all, none of them have fully formed frontal lobes); however, I think they could have been presented with more challenging questions, and the filmmakers should have been all right with an answer of “I don’t know.”

With documentaries, there is often a question of whether the filmmaker should be in or outside of the frame. Should they be a part of the documentary narrative, or should they maintain a certain level of distance and detachment? There are great documentaries that take both forms. There is no way of knowing, but I have sneaking suspicion that Green might have  been better served presenting some context for each of these stories. Give us some narration that might help us place the feelings of these three teens within a bigger picture so that maybe the audience could begin to grasp the external elements at play in these three individual stories.

been better served presenting some context for each of these stories. Give us some narration that might help us place the feelings of these three teens within a bigger picture so that maybe the audience could begin to grasp the external elements at play in these three individual stories.

As it stands, the documentary gives us an immersive look into the lives of three (not terribly diverse) teens and how they personally go through the grind of the good and the bad (probably mostly bad) of Instagram life. However, as tiring and disturbing as some of the documentary ends up being, I was left with a big question at the end: what now? And it is this simple nagging question that makes me think that, for all of this film’s positives, it failed to give us anything truly substantive to challenge, shift or transform our paradigms around social media, technology, and the internet.