Toni Erdmann is about the lengths one might go to pursue someone and the ways we mask such a longing for connection under a facade of professional ambition. It’s about the clash that can occur when an eccentric personality plants himself in the company of a formal society. And it’s a nearly three hour German film with an oddly surrealist flavour.

Toni Erdmann is about the lengths one might go to pursue someone and the ways we mask such a longing for connection under a facade of professional ambition. It’s about the clash that can occur when an eccentric personality plants himself in the company of a formal society. And it’s a nearly three hour German film with an oddly surrealist flavour.

Winfreid (Peter Simonischek) is a tousle-haired older man who lives alone with his dying dog. His job at an elementary school provides an outlet for a strange, childlike sense of humour, but in his normal life these jokes makes him appear almost unhinged. He dresses up as a drug-dependent escaped convict when the delivery man knocks on his door; he arrives at a family gathering with zombie makeup; he constantly gives in to the temptation to insert a pair of false teeth kept at the ready in his breast pocket. Quite often these jokes fall flat, usually because he is reluctant to carry them to the end, giving away the punchline in an apologetic attempt to connect with the human in front of him. I got the feeling that Winfried relied on these jokes to mask the pain of his lonely life, to make something special out of his humdrum existence.

His adult daughter, Ines (Sandra Hüller), perhaps attempting to avoid her father’s fate, is busily climbing the professional ladder in the international world of cooperate business. Her life bears the emblems of constant hard work. While she enjoys the accompanying status of being before and important, she hardly seems happy wearing its persona. When she flies home to attend a family gathering, she spends the bulk of her time in the yard conducting business on her mobile phone. Perhaps this bustle is justified, but it also feels like an attempt to avoid being alone with her father. When Winfreid walks into the backyard and briefly catches her off her phone, she quickly puts the receiver back to her ear rather than be caught alone with her dad.

Winfreid, recognizing this in his daughter, and maybe aware of his own unease, announces that he is flying to her rented flat in Romania to spend several days with her. Ines puts up with this inconvenience, but her busy schedule of client meetings and late night schmoozing means the only way for them to spend time together is for him to accompany her to these important meetings. Of course, given his bumbling personality, he embarrasses her in front of clients during a high stake meeting. Yet it also provides a front row seat for him to recognize the dull ache of her discontent and the harsh creature of power she has become. “Are you really human?” he asks in a moment of clarity. But the question pierces a little more than he intended so he lets it go, mumbling a “never mind.”

Winfreid, recognizing this in his daughter, and maybe aware of his own unease, announces that he is flying to her rented flat in Romania to spend several days with her. Ines puts up with this inconvenience, but her busy schedule of client meetings and late night schmoozing means the only way for them to spend time together is for him to accompany her to these important meetings. Of course, given his bumbling personality, he embarrasses her in front of clients during a high stake meeting. Yet it also provides a front row seat for him to recognize the dull ache of her discontent and the harsh creature of power she has become. “Are you really human?” he asks in a moment of clarity. But the question pierces a little more than he intended so he lets it go, mumbling a “never mind.”

As for Ines, the whole visit and the way his presence cracks open her polished personality are a terrible inconvenience, as awkward as smashing her toe on the cot she rolls out for him to sleep on. When the visit ends, she formally bids him farewell and returns to her flat in a rush of busyness. Once safe in her apartment, she lingers at the window watching him enter his taxi and dissolves into sobs, like those of a child seeking the comfort only found in a parent’s embrace. Composing herself, she retreats into her meetings, those previous emotions an awkward memory as bothersome as walking in heels with her infected toe.

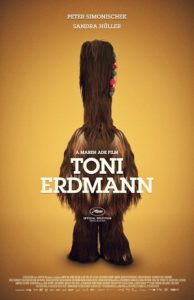

Yet that evening, while on a date with other high-powered business woman, she receives a nasty shock. Her father has not left town, but is instead stalking her at social gatherings while wearing his wig and false teeth, introducing himself to her friends as “Toni Erdman, life coach.” Through a bizarre set of circumstances that she at first is unable to stop and then begrudgingly accepts, he networks his way into her social circle. The rest of the film follows their strange and often hilarious adventures as he follows her to the clubs, accompanies her on high-stake visits to factory sites, and attends her nude birthday party.

Many of these scenes feature surrealism that one would expect in a Luis Buneal film or a Salvador Dali story. What makes them so unsettling in this context is the straight forward, almost documentary filming style of Toni Erdmann. While the occasional blatant sexuality and nudity in this film is integral to the film’s characters and story, it left an unwelcome taste in the mouth, due a large part, I think, to this strange mashup of genres. The long running time also makes me wonder if I can recommend investing yourself in it.

Many of these scenes feature surrealism that one would expect in a Luis Buneal film or a Salvador Dali story. What makes them so unsettling in this context is the straight forward, almost documentary filming style of Toni Erdmann. While the occasional blatant sexuality and nudity in this film is integral to the film’s characters and story, it left an unwelcome taste in the mouth, due a large part, I think, to this strange mashup of genres. The long running time also makes me wonder if I can recommend investing yourself in it.

Yet in the week since I’ve watched it, I’ve found myself becoming more and more impressed by the constant surprises that the film managed to weave into the story, each one so true to the characters that it never felt cheap. The sensitive script, supported by powerfully nuanced acting, resulted in a story that effortlessly tightened, then unwound the tension created by these perfectly believable characters. Toni Erdmann asks us to contemplate the loneliness so often masked by ambition or frivolity and makes us ponder the lengths we might go to pull others back to us. What small steps might I take to maintain such connections before similarly drastic action is required? Films this dense and unusual don’t come around often.