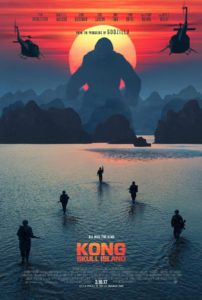

Opening to an estimated 61 million dollar weekend, Kong: Skull Island, the sophomore film in Legendary’s MonsterVerse, virtually guarantees that we’ll get to see giant monsters duke it out on the big screen for years to come. Twelve-year-old me is shouting for joy. And while a number of moviegoers were slightly underwhelmed at the amount (or lack thereof) of monster-on-monster mayhem featured in Gareth Edwards’s 2014 Godzilla, it’s hard to imagine anyone leveling that complaint at Kong: Skull Island. Indeed, some critics argue that that the latter overcompensates for the perceived failures of the former. There’s probably a bit of truth to that claim, but more importantly, I suggest that the tonal chasm between these two films presents us with a glimmer of hope that there will be room for a diverse set of stories in this MonsterVerse. Whatever the case may be—only time will tell—Skull Island is ultimately an enjoyable creature feature that (mostly) succeeds at providing audiences with a couple of hours of spectacle-filled entertainment.

Opening to an estimated 61 million dollar weekend, Kong: Skull Island, the sophomore film in Legendary’s MonsterVerse, virtually guarantees that we’ll get to see giant monsters duke it out on the big screen for years to come. Twelve-year-old me is shouting for joy. And while a number of moviegoers were slightly underwhelmed at the amount (or lack thereof) of monster-on-monster mayhem featured in Gareth Edwards’s 2014 Godzilla, it’s hard to imagine anyone leveling that complaint at Kong: Skull Island. Indeed, some critics argue that that the latter overcompensates for the perceived failures of the former. There’s probably a bit of truth to that claim, but more importantly, I suggest that the tonal chasm between these two films presents us with a glimmer of hope that there will be room for a diverse set of stories in this MonsterVerse. Whatever the case may be—only time will tell—Skull Island is ultimately an enjoyable creature feature that (mostly) succeeds at providing audiences with a couple of hours of spectacle-filled entertainment.

Set in the 1970s, Kong: Skull Island centers around a group of scientists, soldiers, and government officials who travel to a recently discovered island filled with scores of vicious creatures, including the titular Kong. The cadre of (mostly) unsuspecting adventurers soon find themselves stranded on the island, where they have to fight for their survival. Monsters fight humans. Humans fight monsters. Monsters fight monsters. And that’s about it.

Skull Island is an intentionally simple story, and that’s all it has to be in order to be a boatload of fun. The human cast is a mostly forgettable lot, save for Hank Marlow, played by a John C. Reilly who is perfectly typecast here as the island’s resident crazy. It’s not so much that the rest of the cast turns in a bad performance as much as it is that their characters are so thinly sketched that there isn’t much to work with. Humans in Kong: Skull Island are, first and foremost, a vehicle through which we get to see a giant ape kill ancient monsters. And again, it’s a lot of fun to watch. Additionally, the film is bolstered by a very impressive score; and while a lot of people are talking about the film’s use of 70s hits, Henry Jackman’s compositions work wonders for the film and deserve more attention than they’re getting. Last year, Jackman scored the wildly popular fourth entry in Naughty Dog’s Uncharted video game series, and he taps back into that musical well for Skull Island, imbuing a number of scenes with a sense of adrenaline-pumping mystery that would be otherwise absent.

Larry Fong serves as the DP here, and for those familiar with his work as a longtime collaborator with Zack Snyder, it should come as no surprise that he has created some truly stunning visual compositions. His predilection for high-contrast palettes is on full display here, as fiery reds are frequently paired with the darkest of greens and blacks.

But as visually stunning, wildly entertaining, and sonically pleasing as it is, Kong: Skull Island, never quite conjures up the sense of awe and wonder as  Edwards’s Godzilla—for me, at least. Even if you’re not particularly sold on Edwards’s more restrained approach (which I am), it can hardly be denied that he is a master at creating a massive sense of scope and scale in his films. He favors a grounded perspective, in which he places his camera at or near the level of human characters, forcing us to peer up a the looming giants above. And it’s precisely this sense of grandeur that’s missing from Jordan Vogt-Roberts’s Skull Island. While there are, of course, some shots of Kong stomping on humans and whatnot, more often than not, Roberts’s camera soars far above the film’s puny humans, making it incredibly difficult for us to understand just how big these creatures are. On the other hand, the camerawork here seems perfectly at home with the stylized approach Roberts and Fong adopt throughout the film as a whole.

Edwards’s Godzilla—for me, at least. Even if you’re not particularly sold on Edwards’s more restrained approach (which I am), it can hardly be denied that he is a master at creating a massive sense of scope and scale in his films. He favors a grounded perspective, in which he places his camera at or near the level of human characters, forcing us to peer up a the looming giants above. And it’s precisely this sense of grandeur that’s missing from Jordan Vogt-Roberts’s Skull Island. While there are, of course, some shots of Kong stomping on humans and whatnot, more often than not, Roberts’s camera soars far above the film’s puny humans, making it incredibly difficult for us to understand just how big these creatures are. On the other hand, the camerawork here seems perfectly at home with the stylized approach Roberts and Fong adopt throughout the film as a whole.

In a number of different places, Kong: Skull Island tries to prove that it has a brain on its shoulders; but the film’s thinly-veiled commentary on the Vietnam War is largely ineffective and vapid. One thing that is interesting, however, is how the two films in Legendary’s MonserVerse seem to build upon the nuclear subtext of Kaiju films of the 50s and 60s by bringing issues of environmentalism and climate change into focus. This is, admittedly, more of a concern in Godzilla (2014) than in Skull Island, but it is worth pointing out that the latter film goes to some lengths to depict its titular island as a veritable eden, a promised land of sorts, untouched and resplendent in its natural state. It should come as no surprise to those who have been inculcated into the Christian story, therefore, that the the arrival of a human presence on the island spells doom for its inhabitants plant and animal alike. In a couple of brief shots, we see animals run for cover as the so-called scientists drop bombs, destroying paradise in the name of research. We’re not given long to meditate on these implications, however, as a gargantuan ape looms in the background, silhouetted by a blazing sun. It’s monster mash time.

Entertainment is not mindless. But Kong: Skull Island proves that it can come pretty darn close.