Pixar has always been a master engineer of, as Roger Ebert calls films, “machines that generate empathy.” Starting from their earliest SIGGRAPH short films, even the few clunkers of the nearly 30 (count ’em!) films they’ve released drip with empathy. Every Pixar film has made somebody cry. Their best ones have made everyone cry.

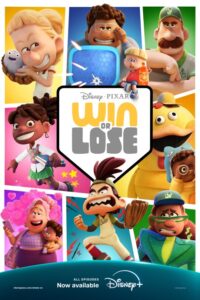

And so it makes sense that their first non-spinoff television project could have been entitled Empathy: the Series. They’ve taken their finely-honed storytelling and empathy-generating skills and created Win or Lose. Part Inside Out, part Turning Red, its very blurry line between imagination and reality lends itself perfectly to the mix of animation styles throughout the series, putting different characters’ inner lives, coping mechanisms, and anxieties into discussion with one another (sometimes literally). The show is at times hilarious and heartbreaking, its music and animation the top-tier audiovisual masterpieces that we’ve come to expect from Pixar over the last thirty (count ’em again!) years.

And so it makes sense that their first non-spinoff television project could have been entitled Empathy: the Series. They’ve taken their finely-honed storytelling and empathy-generating skills and created Win or Lose. Part Inside Out, part Turning Red, its very blurry line between imagination and reality lends itself perfectly to the mix of animation styles throughout the series, putting different characters’ inner lives, coping mechanisms, and anxieties into discussion with one another (sometimes literally). The show is at times hilarious and heartbreaking, its music and animation the top-tier audiovisual masterpieces that we’ve come to expect from Pixar over the last thirty (count ’em again!) years.

Spoiler alert! Plot details for Pixar’s Win or Lose below.

Soda pop prophet Odo (whose name, according to producer David Lally, stands for “Orange Drink Oracle”) takes a stab at identifying the theme of the series at the top of the very first episode: “maybe winning is just a matter of how you look at it.” The subsequent eight episodes provide a Rashomon-like exploration of how eight different people associated with the “Pickles,” a middle-school softball team, experience the week before the State Softball Championship—resulting in a story without any villains or heroes, just a bunch of normal people having a rough week.

Soda pop prophet Odo (whose name, according to producer David Lally, stands for “Orange Drink Oracle”) takes a stab at identifying the theme of the series at the top of the very first episode: “maybe winning is just a matter of how you look at it.” The subsequent eight episodes provide a Rashomon-like exploration of how eight different people associated with the “Pickles,” a middle-school softball team, experience the week before the State Softball Championship—resulting in a story without any villains or heroes, just a bunch of normal people having a rough week.

Because we see the events of the show from different perspectives, we get to know all of the characters quite well (and if you’re like me, immediately dub the star of each successive episode your “new favorite”), leading to a gut-wrenchingly deep empathy for Laurie, Frank, Rochelle, Vanessa, Ira, Yuwen, Kai, and Coach Dan. One of my favorite repeated experiences during the show was finishing an episode absolutely certain that I hated a character for what they had done, only to find out in a subsequent tear-jerking episode what led the “villain” to act that way.

The magic trick the show pulls is that it generates all of this empathy without letting any of the characters off the hook. The characters who did bad things actually did bad things, and the show never tries to pretend that they didn’t; you just find out that they’re not monsters, but humans. And because they’re humans, you can forgive them.

In fact, I think I’d take issue with Odo’s pronouncement that winning is “a matter of how you look at it.” As for themes, the title of the show gestures to the old adage: it’s how you play the game. But what that old saw lacks in specifics about how you should play the game, the show fills up with detail: play the game with care for your opponents. Play the game with a love for your teammates. Play the game with respect for those who make up the fabric of your life, even those who don’t deserve it. In short, play the game with empathy.

But the series came out a single day after professional theologian and online provocateur Joe Rigney published his book The Sin of Empathy: Compassion and Its Counterfeits, ten days before provocateur and professionally-online C.E.Bro Elon Musk appeared on a podcast saying “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy,” and only a month after newly-re-inaugurated President Donald Trump dismissed an episcopal priest’s call to empathy as “not too exciting.”

So it seems like empathy is really going through a rough moment. Interesting time to release “Pixar’s Empathy: The Series,” then—but the thing is, empathy has never been a popular idea. Even among religious folks.

In fact, they killed Jesus for it.

If someone wins, somebody has to lose

The word “empathy” is a comparatively new one, etymologically; only dating as far back as 1909. But it’s been a Christian virtue ever since the Sermon on the Mount. You might be more familiar with its older name: mercy.

Like empathy, mercy is a hard word to pin a definition on, at least in the Bible. Forests have been pulped for the books explaining it, defining its edges, strictly delineating a border between mercy and grace, and yes, decrying it as a sin. But while Jesus doesn’t give a definition, he does give plenty of examples. Every time he’s asked for mercy or tells a parable about mercy, the gift is always unearned and tangible healing: that is, physical blessing, or the forgiveness of sins. But, of course, His biggest example of mercy is in his very life—at great personal cost Jesus came near to us, feeling our pain as his own, and using his own resources to heal us and forgive us.

Even though Pixar’s Win or Lose doesn’t feature an explicit Christ-type character, it does present a parable of mercy. “Are any of these characters evil?” it invites us to ask ourselves. “Which one of these three proved to be a neighbor—er, I mean, a teammate to Laurie?” And then it turns the story around and asks us the question again. “How about now?”

Even though Pixar’s Win or Lose doesn’t feature an explicit Christ-type character, it does present a parable of mercy. “Are any of these characters evil?” it invites us to ask ourselves. “Which one of these three proved to be a neighbor—er, I mean, a teammate to Laurie?” And then it turns the story around and asks us the question again. “How about now?”

A less-thoughtful critic might (as I thought seriously about doing) try to tie each of the characters in the show to one of the Seven Deadly Sins (“um…I guess Yuwen would be pride, and Dan would be wrath…and maybe you could say that Rochelle exemplifies greed?”). But aside from the obvious problem (there are seven deadly sins, but the show focuses on eight characters) and the less-obvious problem (you really have to torture the narrative to make most of them work, especially “sloth”) and the more-obvious problem (the list of “seven deadly sins” is made up anyway), their specific sins aren’t the point of the show.

Rather, the point is that they’re all sinful. None of them are deserving. Even the outcome of the championship game is left ambiguous. And yet they’re all invited to the pizza party at the end, and the show asks us to enter into their pain so that we can see why; to empathize with them, even though they’re flawed; and to get to a core, incontrovertible truth about the Christian virtue—

If they were “deserving,” it wouldn’t be mercy.

Beware the Chicken

Mercy is hard, though. It opens us up to risk: if we get too close, we get entangled and lose control. We could lose money. We might get hurt. Someone undeserving could take advantage of our mercy. Someone malicious or malevolent probably will. It’s not pragmatic in the least to be unselfish, less so still to offer mercy.

But Jesus commands it anyway.

And you can’t say he was ignorant of the risk: Judas did take advantage of his mercy. The entire human race was undeserving. He gave up heaven, he gave up control, he stepped down onto Earth and willingly entangled himself in the malevolent mess of mankind. And he didn’t just get hurt. He died.

Mercy and forgiveness must be free and unmerited to the wrongdoer. If the wrongdoer has to do something to merit it, then it isn’t mercy, but forgiveness always comes at a cost to the one granting the forgiveness.

—Tim Keller,The Prodigal God

Laurie didn’t die for extending mercy to the Pickles, but she did get hurt and taken advantage of. Kai’s mercy toward Laurie led to her getting injured during batting practice. Ira’s mercy hurts him repeatedly. Frank’s sudden mercy for his ex-girlfriend ends with his discovery that she’s found someone else. Rochelle feels like her mercy for her mother has been squandered, and her mother Vanessa’s trust and mercy toward Rochelle is taken advantage of. Dan’s mercy for his team is rewarded with the parents’ decision to replace him.

But their decisions to extend mercy are nonetheless shown, at every turn, to have been the right decision. Despite the well-founded fears of being hurt because of their empathy, the Pickles’ decision to extend it was right—in the eyes of the show, and in the eyes of Jesus.

Refusing to extend empathy doesn’t just reject Jesus’ command, it says that you don’t think that he can be trusted—that he doesn’t know the stakes, that he doesn’t know the evil that we’re facing—but come on, Jesus is the only one who has ever had a perfect view of both.

Our job is to love others without stopping to inquire whether or not they are worthy. That is not our business and, in fact, it is nobody’s business. What we are asked to do is to love, and this love itself will render both ourselves and our neighbors worthy.

—Thomas Merton, in a letter to Dorothy Day

He raised Jairus’ daughter from the dead, even though Jairus was a member of the religious leadership that opposed him at every turn. He healed the centurion’s servant in Capernaum, even though the Roman army he served in was brutal. He empathized with the Samaritan Woman at the Well, telling her deep truths about the Kingdom, even though she was an adulteress and a member of a culture who had set themselves against God’s people. He even granted the demons’ request to send them into a herd of pigs instead of destroying them, and they definitely didn’t deserve Jesus’ mercy. And during his last week before the cross, Jesus extended Judas the mercy of his foot-washing at the Last Supper, even though he knew that Judas was about to betray him to the murderous religious leaders who wanted him dead.

Maybe more to the point, Jesus never gives us a list of people that it’s okay to not extend mercy or empathy to; not pharisees (whom he did not have kind words for), nor Judas (whom he did). Neither Jesus nor the apostles who led the Church after His death and ascension tell us that it’s okay to refuse empathy toward the poor, or those we think are lazy, or people who crossed the border illegally, or the residents of another nation. Paul never allows us the comfort of withholding our mercy toward those who will take advantage of our willingness to help, or even those who have already taken advantage of us in the past. John didn’t witness an angel exhorting the Church in Sardis toward mercy, “but not toward people with gender dysphoria. You don’t have to treat them like humans.” Peter doesn’t include any appendices or provisos allowing us to remain merciless toward people of color, or civilians who live in the same jurisdiction as terrorists, or people who shelter the oppressed. In Psalm 25, David writes, “All the paths of the Lord are mercy and truth, to such as keep His covenant and His testimonies.” All the paths. As Charles Spurgeon points out, “There is no exception to this rule…They say there is no rule without an exception, but there is an exception to that rule.”

No, at the end of the Gospels, you don’t get a definition of empathy in words, positively or negatively. But you do meet Jesus, the embodiment of empathy, whose criteria for those who receive mercy is simple: you get mercy from Jesus if you need it. Need is the only requirement; and, just like a middle-school baseball team, the empathy creates a family.

Answer the Call of the Unknown

In a cultural moment that ignores or even repudiates Jesus’ call to empathy, Win or Lose is a reminder that mercy is inherently risky and requires courage: not just because extending mercy demands something of us, but also because the world opposes it. Jesus didn’t find victory in cleverly doling out mercy on merit, but in seeing the risk, counting the cost, and then lavishing mercy on the undeserving anyway.

In a cultural moment that ignores or even repudiates Jesus’ call to empathy, Win or Lose is a reminder that mercy is inherently risky and requires courage: not just because extending mercy demands something of us, but also because the world opposes it. Jesus didn’t find victory in cleverly doling out mercy on merit, but in seeing the risk, counting the cost, and then lavishing mercy on the undeserving anyway.

And then, during one of his explanations of the family of God— a family which cares for those who cannot reciprocate—Jesus minced no words about the right way to respond to the empathy that He showed. He made it simple, almost to the point of laconic, with no exception or qualification:

“Go, and do the same.”