Call anybody you want. They can’t do anything to me, not anymore, and nor can any of you. I am a human being, damn it! […] You can pulp a story but you cannot destroy an idea. Don’t you understand? That’s ancient knowledge. You cannot destroy an idea!

—Benny Russell, Deep Space Nine S6E13 “Far Beyond the Stars”

Since the debut of the Alex Kurtzman-led CBS revival of the franchise, Star Trek has been criticized by some as “too political.” Unlike similar-sounding criticisms of the Star Wars prequels, they’re not referring to the inner machinations of the Romulan Senate or interplanetary trade negotiations with outer rim systems. The sentiment usually refers to the casting choices that led to the title character being the only white male human aboard the La Sirena in Star Trek: Picard, or announcements like the one that transgender and nonbinary actors and characters would be appearing in season three of Star Trek: Discovery.

And, to be sure, the franchise has seen some pretty heavy-handed real-world allegory since its recent revival, like Mirror Universe Lorca’s invocation of a slightly paraphrased Trump campaign slogan during his dictatorial power consolidation. But Star Trek has always been like this. Roddenberry even openly solicited it from prospective writers during The Original Series:

…with that firm foundation (of good storytelling and sci-fi concepts) established, interweave in it any statement to be made about man, society and so on. Yes, we want you to have something to say, but say it entertainingly as you do on any other show.

—Gene Roddenberry, “Star Trek Writers/Directors Guide,” April 1967

Evaluating how much he followed his own rules of building a solid foundation of story first is an exercise best left for the reader, but his intention was clear from the beginning: to tell stories about humanity, to use the future as a lens for the present, to show how humanity could grow and change and still stay the same. Some reports even indicate that he intentionally used racy costuming to slip these allegories past the network censors, so that he could say what he wanted to say without NBC getting antsy.

But it’s more than that, too; in fact, the really memorable times, when it really shines, are those times it’s not just political but theological. Gene Roddenberry’s future is an image of heavenly utopia, and it asks a crucial question that we have to wrestle with whether we’re trying to get there the Star Trek way or the Jesus way: how can we love our neighbor if we’re not willing to listen to their story?*

Politics in the Final Frontier

The Original Series

Star Trek began telling stories of our neighbors all the way back at the beginning: placing a Black woman on the bridge as an equal to the other officers was the thin end of the wedge, followed by a series of stories which challenged white supremacy by setting a Latinx man in authority over Kirk in “The Menagerie” and appointing a Black man to prosecute Kirk in “Court Martial.” It eventually led up to Kirk and Uhura’s famous interracial kiss in season 3’s “Plato’s Stepchildren,” breaking taboos and getting the show canceled in some more conservative American cities. People of Color from the future were telling America their stories with just as much weight and importance as the stories of white people.

Star Trek began telling stories of our neighbors all the way back at the beginning: placing a Black woman on the bridge as an equal to the other officers was the thin end of the wedge, followed by a series of stories which challenged white supremacy by setting a Latinx man in authority over Kirk in “The Menagerie” and appointing a Black man to prosecute Kirk in “Court Martial.” It eventually led up to Kirk and Uhura’s famous interracial kiss in season 3’s “Plato’s Stepchildren,” breaking taboos and getting the show canceled in some more conservative American cities. People of Color from the future were telling America their stories with just as much weight and importance as the stories of white people.

This was certainly a political act, to place non-white people in positions of esteem and authority during the middle of the Civil Rights movement, and to do it casually as if to say, “obviously this is the way the future will be.” But more than that, it was a theological expression of the Imago Dei; “even people who don’t look like you have a valuable story to tell, the same as anyone else, and letting them tell that story is an expression of respect.” Later shows pushed the envelope even further, with a diverse cast of flag officers and important people in the Original Series-era films, The Next Generation, and beyond; but it all began with Nyota Uhura on the bridge in season 1. As people were arguing about whether people of African descent were entitled to the same rights and privileges as those of European descent, Star Trek took up the unequivocal position that it was a settled question, and went about letting them tell their stories.

And it worked. People of all colors heard the story; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously a fan of Uhura’s place on the show, told Nichelle Nichols, “whether you like it or not, you have become a symbol. If you leave, they can replace you with a blonde haired white girl, and it will be like you were never there. What you’ve accomplished, for all of us, will only be real if you stay.” Whoopi Goldberg, who would later become the enigmatic Guinan on The Next Generation, put it more succinctly when she saw Uhura on the Enterprise as a child: “Momma! There’s a black lady on television and she ain’t no maid!”

And it worked. People of all colors heard the story; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously a fan of Uhura’s place on the show, told Nichelle Nichols, “whether you like it or not, you have become a symbol. If you leave, they can replace you with a blonde haired white girl, and it will be like you were never there. What you’ve accomplished, for all of us, will only be real if you stay.” Whoopi Goldberg, who would later become the enigmatic Guinan on The Next Generation, put it more succinctly when she saw Uhura on the Enterprise as a child: “Momma! There’s a black lady on television and she ain’t no maid!”

The Original Series and its films didn’t stop with these theological statements: they commented on the evils of war, the futility of the Cold War (and eventually its end, with The Undiscovered Country), and whether or not it was right for one nation to step in to the affairs of another unasked; but its most enduring legacy is the way it dealt with race.

The Next Generation Era

By the time Picard, Sisko, and Janeway took the conn, the question of the value of non-white people was considered settled. The Civil Rights movement was declared a success, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been lionized into a hero of both Black and white people, and the future that The Original Series had promised seemed to be well on its way. This declaration was certainly premature; but the hope and optimism of the Trek universe, set as it was four centuries away, nonetheless seemed at the time to be less fictional and more scientific.

By the time Picard, Sisko, and Janeway took the conn, the question of the value of non-white people was considered settled. The Civil Rights movement was declared a success, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been lionized into a hero of both Black and white people, and the future that The Original Series had promised seemed to be well on its way. This declaration was certainly premature; but the hope and optimism of the Trek universe, set as it was four centuries away, nonetheless seemed at the time to be less fictional and more scientific.

So the era of Trek kicked off by “Encounter at Farpoint” in 1987 was focused far more on personal worth and freedom than the collective liberation of entire people groups; in The Next Generation, some of the show’s most beloved and groundbreaking episodes were telling “political” stories about the value of individuals. Picard fights for Data’s rights in “The Measure of a Man” and protests the abuse of power in the name of “safety” in “The Drumhead,” both times insisting that the freedom and rights of the individual are crucial not only to that individual, but to society as a whole.

And they didn’t stop at exploring the value of people inside the Federation. TNG’s season 3 episode “The Enemy” tells Bochra’s story of living in a world with exacting, unattainable expectations—the Romulan Empire—giving voice to the story of Starfleet’s longtime villains and showing that the individual is not as simple as their whole kind. Season 5 introduces us to “The Outcast,” a J’naii individual who tells her story to Riker: a desire to be a woman, not an androgynous being. In both cases Picard and his crew listens to their stories and fights hard to show that they are valuable.

And they didn’t stop at exploring the value of people inside the Federation. TNG’s season 3 episode “The Enemy” tells Bochra’s story of living in a world with exacting, unattainable expectations—the Romulan Empire—giving voice to the story of Starfleet’s longtime villains and showing that the individual is not as simple as their whole kind. Season 5 introduces us to “The Outcast,” a J’naii individual who tells her story to Riker: a desire to be a woman, not an androgynous being. In both cases Picard and his crew listens to their stories and fights hard to show that they are valuable.

“Darmok” is my favorite episode of TNG, exploring deeply the reality that knowing another’s story is crucial to understanding them: not only understanding their worldview, but what they’re saying at all. The Universal Translator doesn’t help; Picard has to simply spend time with Captain Dathon, growing in empathy until he is able to piece together the story Dathon is trying to tell him. It is an episode that most literally shows Star Trek’s philosophy of listening to the stories of our neighbors: how could Picard have even understood Dathon without listening to his story? This personal relationship between two individuals proves to be the linchpin of the Federation’s relationship with the Tamarians.

Deep Space Nine took the ball from TNG and ran it further down the field by introducing Jadzia Dax: a joined Trill who is potentially the wisest, most self-secure person on the show, but who Sisko met when she was a man. Her episodes dealt with the worth of people even when they are mentally and emotionally complicated; with the value of those who are spiritually and even sexually intricate. The old Klingon warrior Kor doesn’t skip a beat in season 2’s “Blood Oath” when she tells him of her new identity as Jadzia; though he met Dax as Curzon, his love and care for the person is unchanged. And season 4’s “Rejoined” forces a discussion of same-sex relationships through the metaphor of a Trill taboo against reconnecting with relationships from previous lives, but doesn’t dare to suggest that Dax or Kahn are in any way less meaningful in the eyes of the Federation.

Deep Space Nine took the ball from TNG and ran it further down the field by introducing Jadzia Dax: a joined Trill who is potentially the wisest, most self-secure person on the show, but who Sisko met when she was a man. Her episodes dealt with the worth of people even when they are mentally and emotionally complicated; with the value of those who are spiritually and even sexually intricate. The old Klingon warrior Kor doesn’t skip a beat in season 2’s “Blood Oath” when she tells him of her new identity as Jadzia; though he met Dax as Curzon, his love and care for the person is unchanged. And season 4’s “Rejoined” forces a discussion of same-sex relationships through the metaphor of a Trill taboo against reconnecting with relationships from previous lives, but doesn’t dare to suggest that Dax or Kahn are in any way less meaningful in the eyes of the Federation.

The series also positions Bajorans as an allegory of the Palestinians, Kurds, Jews, and American Indians; as Michael Piller explained to Cinefantastique, “they are any racially bound group of people who have been deprived of their home by a powerful force—” which means that they could easily be reconstrued as the Uyghur or Rohingya today. The stories told by the people of Bajor are saying, “even if this occupation is legal, it is not right.” But, crucially, the really impactful ones are all individual stories; the story of Shakaar, of Li Nalas, and most importantly Kira Nerys.

We also see in DS9 more thoughtful stories of religious people than in most previous incarnations of the franchise; the Bajoran faith is treated with respect and honor when it is practiced with sincerity (such as by Kira, Bareil, and Opaka) and only painted as villainous when it is used as a weapon to accrue and consolidate power (as with the most love-to-hate villain of perhaps the entire Star Trek franchise, Kai Wynn; as well as the Dominion’s Founders). As in the real world, it is what the individual does with their faith that makes them good or evil.

We also see in DS9 more thoughtful stories of religious people than in most previous incarnations of the franchise; the Bajoran faith is treated with respect and honor when it is practiced with sincerity (such as by Kira, Bareil, and Opaka) and only painted as villainous when it is used as a weapon to accrue and consolidate power (as with the most love-to-hate villain of perhaps the entire Star Trek franchise, Kai Wynn; as well as the Dominion’s Founders). As in the real world, it is what the individual does with their faith that makes them good or evil.

But in Voyager, we see one of the most stark and pointed examples of individual value in the franchise: when the crew rescues former Borg Seven of Nine. In one of the most literal examinations of the individual vs. the collective, we get to follow Seven as she becomes a human again; we hear her story told in practically every episode from her introduction through the end of the series. She’s telling stories of the pain that comes from systematic, lifelong abuse; of the difficulty of cult deprogramming; of the helplessness of losing control of your own body; of the uncertainty of coming from a bad situation and always wondering if the new one is worse. Her existence is a profound question, and there’s never a definitive answer.

Voyager also places the holographic Doctor as an heir to the storyline vacated by Data: the Pinocchio character seeking to become a real boy, but with the added pain of being a physician and knowing in painful detail exactly what life is while still being unable to attain it. The Doctor’s story becomes even more poignant as he has to instruct Seven on how to become more human in a story arc alluded to in “The Gift” by way of hair: “I also took the liberty of stimulating your hair follicles,” the notably-balding Doctor tells Seven. “A vicarious experience for me, as you might imagine.” While this might not have seemed political at the time when it aired, the story of an artificial intelligence and its value is being told in the real world today; the laws and ethics surrounding the existence of AI and the responsibilities its creators must hold are in no way theoretical as companies finalize self-driving cars and other “smart” mechanical devices. We may even see stories like Photons Be Free someday: tales written by artificial intelligences, about their experiences.

Voyager also places the holographic Doctor as an heir to the storyline vacated by Data: the Pinocchio character seeking to become a real boy, but with the added pain of being a physician and knowing in painful detail exactly what life is while still being unable to attain it. The Doctor’s story becomes even more poignant as he has to instruct Seven on how to become more human in a story arc alluded to in “The Gift” by way of hair: “I also took the liberty of stimulating your hair follicles,” the notably-balding Doctor tells Seven. “A vicarious experience for me, as you might imagine.” While this might not have seemed political at the time when it aired, the story of an artificial intelligence and its value is being told in the real world today; the laws and ethics surrounding the existence of AI and the responsibilities its creators must hold are in no way theoretical as companies finalize self-driving cars and other “smart” mechanical devices. We may even see stories like Photons Be Free someday: tales written by artificial intelligences, about their experiences.

Political? Or Theological?

“Theological?” one might reasonably protest: the well-known secular, Gene Roddenberry, creating a theological show? Well, it probably wasn’t intentional. But the setting of Star Trek, the core of its very existence, its new civilization full of new life, is based on one simple, rock-solid idea that is shot through deeply with theology: the contention and certainty that sentient beings have inherent worth and value, that they deserve to exist and thrive, and that they deserve to have their stories heard.

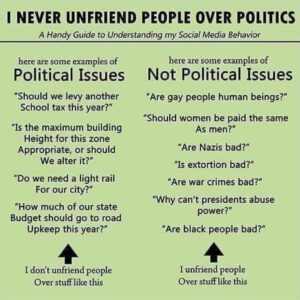

I can’t trace the origin of a poignant image further back than late April of 2020, but in it a contrast was made between political issues (such as “should we levy another school tax this year?,” “do we need a light rail for our city?,” and “how much of our state budget should go to road upkeep this year?”) and issues which are not political (such as “are Nazis bad?,” “is extortion bad?,” and “do Black people have value?”). These questions can be boiled down to being about or not about the Imago Dei, the Christian doctrine that all humans have inherent worth and value because they are made in the image of God: regardless of what they look like, or what sin they might commit, or what good they might do; people have value. Issues that hinge upon whether or not humans have inherent worth are theological, then; not political.

I can’t trace the origin of a poignant image further back than late April of 2020, but in it a contrast was made between political issues (such as “should we levy another school tax this year?,” “do we need a light rail for our city?,” and “how much of our state budget should go to road upkeep this year?”) and issues which are not political (such as “are Nazis bad?,” “is extortion bad?,” and “do Black people have value?”). These questions can be boiled down to being about or not about the Imago Dei, the Christian doctrine that all humans have inherent worth and value because they are made in the image of God: regardless of what they look like, or what sin they might commit, or what good they might do; people have value. Issues that hinge upon whether or not humans have inherent worth are theological, then; not political.

And those are the kinds of big questions that Star Trek has asked, by and large, since its inception in 1966. It has then assumed that they do have inherent worth and asked them to tell their stories. And tell them they have: Uhura and Kirk in 1968, and Stamets and Culber in 2017. Kirk railing against blind hatred based on race in 1969, and Picard decrying abandonment of refugees in 2020. You may disagree with how heavy-handed it can be, but the stories themselves have always been core to the franchise’s DNA.

Still, I agree that in some ways it does feel different now; and I wonder if it’s because, rather than leading the curve as they were in the 1960s and 1990s, Star Trek is following the curve; after all, homosexual relationships have been present in pop culture for decades now. Maybe these events feel political because Trek is behind the curve; it’s dealing with the Imago Dei in ways that the rest of the culture already got to, rather than leading the charge, so we’ve already seen them politicized and the battle lines drawn. Our polarized culture has already prepared us to fight over these issues that aren’t political but theological, and primed us to not listen to their stories. It’s living in a world of its own making, which means it really has to stretch to make the commentary work.

Still, I agree that in some ways it does feel different now; and I wonder if it’s because, rather than leading the curve as they were in the 1960s and 1990s, Star Trek is following the curve; after all, homosexual relationships have been present in pop culture for decades now. Maybe these events feel political because Trek is behind the curve; it’s dealing with the Imago Dei in ways that the rest of the culture already got to, rather than leading the charge, so we’ve already seen them politicized and the battle lines drawn. Our polarized culture has already prepared us to fight over these issues that aren’t political but theological, and primed us to not listen to their stories. It’s living in a world of its own making, which means it really has to stretch to make the commentary work.

But that doesn’t mean Trek is “too political” these days. It just means that we’ve already heard these folks’ stories, and people who object to it have already voiced their objections.

Stories of the Image of God

The stories of new life and new civilization are clearly not-so-secretly about humanity today; Star Trek has long endured because it tells stories of us, about the Imago Dei, and about our value.

So how do we value the Imago Dei in those who are different from us?

We listen to their stories.

Some Christians think this is like winking at their sin, giving them a pass on something they should feel conviction about; but really it’s just loving them like Christ did. His words to the hurting were insightful because He was the omniscient Son of God, and He knew their stories inside and out! He proved that we can’t love others well if we’re not willing to listen to their stories; we can’t see what they need, or know what really hurts or grieves them.

It’s also important to remember that we aren’t God; it’s not our responsibility to convict others of sin, it’s the Holy Spirit’s. We were never given that job, because aside from the work of Christ we’re in the same state. Instead, we call people to repentance, and we welcome them with open arms. We help where we can. Like Jesus, we do what we can to ease their suffering.

This shouldn’t be political; if it seems to you like it is, that’s fine. The culture, and especially Christian culture, is awash in an insistence that our tribe is good, all other tribes is bad, and even so much as treating them like people can contaminate us. It’s part of life in this polarized, fallen, defeated world.

But it’s not part of New Life in the New Civilization. Jesus sent us (and prayed for us) that we would be loving. And to do that, we first have to listen: to people we don’t agree with. To people who don’t look like us. To people who are saying things we think are despicable. To people who are saying things we don’t understand. To people who see the world through different experiences. To people who say that privilege exists. To people who say that privilege doesn’t exist. To people who vote differently from us. To people who speak different languages. To people who know more than us. To people who know less than us. But especially to the hurting, the lost, the weak, and the broken. We’re the hands and feet of the Savior on Earth; put in Trek terms, we’re the only ship in range.

Hailing frequencies open.

* My wife Natalie originally came up with the question that became the core of this article—”how can we love our neighbor if we’re not willing to listen to their story?”—because she’s brilliant.