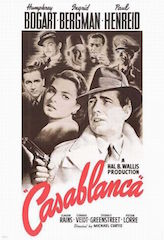

If you asked me about my top 10 favorite films of all-time, Casablanca would be on the list. It’s romantic, witty, adventurous. It is both ahead of its time and incredibly timely. The doomed romance between Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) and Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman) is evocative, complex, and fulfilling.

If you asked me about my top 10 favorite films of all-time, Casablanca would be on the list. It’s romantic, witty, adventurous. It is both ahead of its time and incredibly timely. The doomed romance between Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) and Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman) is evocative, complex, and fulfilling.

What gets me about Casablanca is how immensely entertaining and romantic it can be with very little action. The plot moves forward mostly through conversations, discussing what has happened or what will happen or what could happen. That’s the power of great dialogue, and Casablanca has it in spades. There are so many classic lines here that other brilliant moments are almost forgotten, such as Rick’s numerous dry quips and retorts:

“Where were you last night?”

“…That’s so long ago, I don’t remember.”

“Will I see you tonight?”

“…I never make plans that far ahead.”

Rick’s focus on the present is apt for the environment where he’s set up shop. The city of Casablanca serves as a sort of purgatory, a vulgar and godforsaken nest of perpetual delay. Everyone in Casablanca is waiting for something, longing for the day of release. Until then, they wait…and wait…and *wait.* Rick cannot admit to himself what he’s waiting for, or rather who he’s waiting for. He’s caught in the web of internal turmoil, both desiring to see her come through his doors and distraught when she finally does.

Casablanca exhibits what we could call “on-screen chemistry,” and not just between Bogart and Bergman. Yes, they’re incredibly romantic—he’s a soft-hearted rogue, she’s a vulnerable beauty—but you could argue that Bogart and Claude Rains have just as much on-screen chemistry. When Rick tells Louis he believes this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship, we believe him; we know this friendship began long ago. Louis clearly respects Rick, which is saying something for a man who doesn’t much respect anyone, including himself. Louis is the sort of man who will openly share with others about manipulating a young woman to offer him sexual favors in return for approval of visa papers. He’s unapologetic about this, but also not entirely angry with Rick when the plot is foiled by a rigged roulette game. Louis almost seems amused and tells Rick there’ll be a blonde to replace her by the morning. Louis is highly aware of the louse he truly is; his lack of scruples and self-serving maneuvers are the opposite of Victor Laszlo’s, the anti-Nazi rebel and the monkey wrench in Rick’s romantic hopes.

In terms of morality and values, Rick finds himself caught between being a Laszlo and a Louis—he’s both a man of principle and a man of survival, at once tender and aloof. Ilsa brings out the better side of him, but it’s a side that’s open to being wounded. Louis notes that Rick is the sort of man women would fall in love with, but I’m not sure he’s the sort of man they *should* fall in love with. He’s a gun for hire, a lone wolf. When asked about his nationality, he responds “a drunkard.” And he is—there are hints that Rick has had drinking problems in the past, and the return of Isla brings him back to the bottle. Still, he’s also the sort of man who, while claiming at least twice that he won’t stick his neck out for nobody, does give of himself for the sake of others.

If any woman could make a man drink himself under the table or give up his own freedom and future for a plane ticket, it’d be Isla. Yet she doesn’t do any of this by manipulation or power grabs. She’s unique in the pantheon of leading ladies in that she’s both strong and weak; she has limited agency and almost a childlike way about her. She fawns over Laszlo with doe-like eyes; she tells Rick to do the thinking for both of them. This doesn’t exactly make her the strongest feminist, but she’s also not simply empty-headed arm candy—she has the strength to pull a gun on Rick and the wherewithal to leave Rick twice, first in Paris and then on a plane to Lisbon. She’s not a feisty firebrand or a femme fatale; she’s simply Ilsa, alluring and spirited, a one-of-a-kind woman. I confess, I may have developed a bit of a crush on Ingrid Bergman the first time I watched Casablanca.

In a culture where marital fidelity is often cheapened both on and off screen, Casablanca features not one, but two acts of sacrifice on Rick’s part of the sake of a marriage. Yes, Rick puts Ilsa on the plane with her husband, knowing he’s losing any possible chance of their future love for the sake of her marriage and well-being. Yet Rick also saves a young bride from performing sexual favors for Louis, giving up a significant amount of money so she wouldn’t have anything to hide from her husband. Casablanca is one of the few films that navigate romantic love and complex ethical dilemmas with a sense of virtue and ease. In both of these instances, it requires great sacrifice on Rick’s part for the sake of another, where Rick gains little to nothing in return, apart from simply doing the right thing. He helps someone in need at great cost to himself, and in doing so, affirms marital commitment. For a hard-hearted rogue who won’t stick his neck out for nobody, I’d call that redemption.