“Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?” – Matthew 7:3

“Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?” – Matthew 7:3

Is there anything more despicable than the thought of bringing harm to a child? We even have words to describe people who do – barbaric, contemptible, deranged, monstrous, heartless. These are adjectives we reserve for the lowest of the low in our society. And, one might be hard-pressed to find someone more loathed the world over than a child killer. It takes a twisted kind of sickness, we reason, for anyone to take the life of the innocent; thus, these chiefs of sinners garner very little of our sympathy.

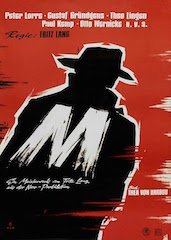

For his first sound film, early visionary director Fritz Lang brings every parent’s worst nightmare to the screen with his masterpiece M released in 1931. A murderer is on the loose in Berlin and the elusive criminal preys on the city’s unsuspecting children. The film opens as the killer plans to strike again. Little Elsie Beckmann makes her way home one afternoon as her mother prepares dinner while she waits for her daughter’s return. Poor Elsie never reaches home after she crosses paths with the city’s most wanted man Hans Beckert (played to eerie perfection by Peter Lorre). Lang introduces us to this troubled man via his shadow obscuring his very own wanted poster. He whistles a cheery tune and buys the girl a balloon, but the sense of dread is palpable as Lang cuts back and forth between this scene and Elsie’s increasingly anxious mother staring at the clock. Finally, the girl’s ball rolls out from behind a bush and her balloon gets caught in some telephone wires. Lang graciously keeps the atrocity off screen utilizing these visual cues to clue us into Elsie’s fate. The result is utterly bone chilling.

What follows is a riveting cat-and-mouse thriller as the entire city turns itself inside out to capture Elsie’s killer and bring him to justice. The police are working overtime increasing their raids on seedy dives and stopping any given passerby on the suspicion of other wide-eyed civilians. Lang realistically captures public outcry and the subsequent fallout of incidences like these. Paranoia spreads like wildfire, and everyone adopts an accusatory posture toward his or her fellow neighbor. The media preys on growing public fear and the suspension of citizens’ right to privacy quickly become the status quo. It’s not long, however, before the criminal underworld decides to fight back. With the black market significantly disrupted by constant raids, the city’s top criminal bosses meet and resolve to commence their own manhunt. With the child killer out of the way, business should go back to normal. With both sides of the law in full pursuit, it becomes only a matter of time until Beckert gets caught.

Lang tells this story primarily utilizing exquisitely edited montages overlaid with expository voiceover narration. It’s evident that the director has only just emerged from the silent era with portions of the street action eerily devoid of sound. Coupled with Lang’s stunning use of shadow and acute attention to lighting, the aesthetic of M unmistakably boasts a proto-film noir technique. It’s no secret that Lang served as one of the pioneers of the subgenre that swept the industry on the other side of the Atlantic in the decade to come, and M remains the perfect template for the dark, stylish Hollywood films to come.

Lang tells this story primarily utilizing exquisitely edited montages overlaid with expository voiceover narration. It’s evident that the director has only just emerged from the silent era with portions of the street action eerily devoid of sound. Coupled with Lang’s stunning use of shadow and acute attention to lighting, the aesthetic of M unmistakably boasts a proto-film noir technique. It’s no secret that Lang served as one of the pioneers of the subgenre that swept the industry on the other side of the Atlantic in the decade to come, and M remains the perfect template for the dark, stylish Hollywood films to come.

As a showcase of technical wonders, M’s reputation is unimpeachable – it (rightfully) consistently pops up in the endless discussion of the greatest films of all time. And yet, it’s in Lang’s narrative denouement where the film’s real power lies. Despite the best efforts of the city’s police force, the band of criminals gets to Beckert first. They capture the killer, sweep him away to some clandestine location, and unceremoniously throw him in front of an unexpected kangaroo court in the basement of a deserted warehouse. Here – before a self-appointed jury of crooks, thieves, pimps, prostitutes, and other murderers – Hans Beckert is tried for his unconscionable crimes. But, as this is no real trial, his accusers have no interest in his defense. Before this riotous throng of other criminals, the man falls to his knees begging for mercy, pleading insanity. His plea evokes the words of St. Paul from the book of Romans where the apostle laments, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.”

It’s a profoundly unsettling moment. Lang has brilliantly forced a shift in his audience’s allegiances, if only momentarily. Is it possible that even after we’ve learned of all this killer has done, we still might feel compassion for him? Of course, the apostle Paul’s words are not meant as an excuse for immoral behavior; he later admits that it’s sin that dwells within that compel him to do what he hates. And, of course, a man who takes the life of a child should absolutely be held accountable for his actions. But, it’s no coincidence that Lang challenges us to consider the hypocrisy of Beckert’s makeshift trial. How can a murderer so swiftly, so willingly cast the first stone at another murderer without any semblance of self-reflection? Suddenly, as the accused stares at his accusers, the divide between them becomes more of a mirror than a barrier separating the innocent from the guilty. For now, we see the accuser stands accused as well.

Every time I revisit M, I am reminded of a particularly haunting song by recording artist Sufjan Stevens. On “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” Stevens recounts the deeply disturbing story of a real-life serial killer who assaulted and murdered, at least, thirty-three teenage boys in the 1970s. Stevens’ light, airy voice and his gorgeous piano melody belie the horrifying lyrics he sings that paint a picture difficult for any listener to stomach. Again, is there anything more despicable than bringing such harm to a child? But, powerfully, in the song’s outro Stevens admits “in my best behavior I am really just like him / look underneath the floor boards for the secrets I have hid.” Most of us have hopefully never committed murder, but have any one of us led lives completely free of unspeakable deeds? Or free enough to comfortably accuse those we deem worse than ourselves? Are we not all equally guilty? For the Christian, then, the final moments of Lang’s arguably greatest film should serve as a reminder that none of us is blameless. And, that should cause us to pause before we so swiftly move to accuse those around us.

Every time I revisit M, I am reminded of a particularly haunting song by recording artist Sufjan Stevens. On “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” Stevens recounts the deeply disturbing story of a real-life serial killer who assaulted and murdered, at least, thirty-three teenage boys in the 1970s. Stevens’ light, airy voice and his gorgeous piano melody belie the horrifying lyrics he sings that paint a picture difficult for any listener to stomach. Again, is there anything more despicable than bringing such harm to a child? But, powerfully, in the song’s outro Stevens admits “in my best behavior I am really just like him / look underneath the floor boards for the secrets I have hid.” Most of us have hopefully never committed murder, but have any one of us led lives completely free of unspeakable deeds? Or free enough to comfortably accuse those we deem worse than ourselves? Are we not all equally guilty? For the Christian, then, the final moments of Lang’s arguably greatest film should serve as a reminder that none of us is blameless. And, that should cause us to pause before we so swiftly move to accuse those around us.

Awesome choice. I haven’t seen this one yet, though I really enjoy Fritz Lang. After reading this I’ll be putting it on my list!