Unlike other comedic stars of the silent film era, Buster Keaton stands above comparisons to his most obvious counterpart, Charlie Chaplin. Keaton was a different kind of man making different films. In his movies, Keaton has been described as “a modern visitor to the world of silent clowns.” His composure and facial expressions lack the befuddled high jinks of “The Tramp” and exhibit a contemplative and resourceful mind in the face of comedic happenstance. It’s a different sort of comedy that is less emotive and born more out of the situations his character’s endure with somber diligence.

Unlike other comedic stars of the silent film era, Buster Keaton stands above comparisons to his most obvious counterpart, Charlie Chaplin. Keaton was a different kind of man making different films. In his movies, Keaton has been described as “a modern visitor to the world of silent clowns.” His composure and facial expressions lack the befuddled high jinks of “The Tramp” and exhibit a contemplative and resourceful mind in the face of comedic happenstance. It’s a different sort of comedy that is less emotive and born more out of the situations his character’s endure with somber diligence.

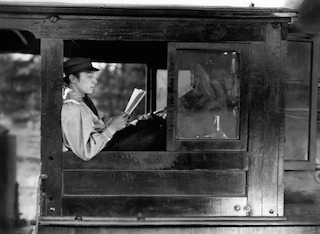

In The General, one of Keaton’s most acclaimed silent comedies, Keaton plays train engineer Johnnie Gray. As the opening still explains, Johnnie has only two loves; his train, the eponymous General, and sweet Annabelle Lee (Marion Mack). After stopping “The General” in Marietta, Georgia, Johnnie immediately departs to visit his lady love. While visiting Annabelle, her brother arrives to announce to Annabelle’s father that the South has fired on Fort Sumter and, “the war is here.” Johnnie runs to enlist at the behest of his paramour but is subsequently denied the opportunity to enlist since he is “more valuable” to the South as an engineer. Annabelle’s father and brother mistake his rejection as Johnnie’s refusal to enlist and Annabelle says she wants nothing to do with him until she sees him in a uniform. Dejected, Johnnie sits on the piston arm of his train and one of the more memorable shots of the movie is created as the train slowly drives away with Johnnie still sitting on the arm, bobbing up and down, thinking of his lady love, unaware of his precarious seat.

From the opening, Keaton’s movie separates itself from common expectations of silent comedies. For one, Keaton’s contemplative Johnnie does not react how we would expect either silent film or modern actors to react to comedic situations. Two early situations where Johnnie should be goaded into reactive, jokey facial expressions are played with a collected deadpan. The actor has said before from an early age as a Vaudeville performer with his parents, he learned the art of deadpan to elicit more laughs from audiences. A substantial reason The General is so funny is Keaton’s non-reaction to absurd events that connects him with the everyman and distances himself from the performing goofball of the slapstick comedy of his era.

Equally surprising is Keaton’s Johnnie being the hero and protagonist of the film as a Southerner and Confederate during the Civil War and the Union being portrayed as the sinister schemers and enemies. After Johnnie’s failure to enlist, the movie cuts to a Union general and his chief spy planning a clandestine mission to masquerade as Confederate soldiers, sabotage the Southern rails, and provide supplies for their advancing Union army. The story is based on the memoir of William Pittenger, Daring and Suffering, a History of the Great Railroad Adventures, a Union soldier that was a part of the real group the movie’s antagonists are based on. However, unlike Walt Disney’s adaptation of this story, 1956’s The Great Locomotive Chase, the Union spies are not the good guys, but the bad guys. Artistically it matters little to the motivations of our main characters, it seems worth mentioning the Confederates are given the heroic spotlight, a choice that would not be made so casually today unless the hero was a bumbling moron like Joe Dirt.

Equally surprising is Keaton’s Johnnie being the hero and protagonist of the film as a Southerner and Confederate during the Civil War and the Union being portrayed as the sinister schemers and enemies. After Johnnie’s failure to enlist, the movie cuts to a Union general and his chief spy planning a clandestine mission to masquerade as Confederate soldiers, sabotage the Southern rails, and provide supplies for their advancing Union army. The story is based on the memoir of William Pittenger, Daring and Suffering, a History of the Great Railroad Adventures, a Union soldier that was a part of the real group the movie’s antagonists are based on. However, unlike Walt Disney’s adaptation of this story, 1956’s The Great Locomotive Chase, the Union spies are not the good guys, but the bad guys. Artistically it matters little to the motivations of our main characters, it seems worth mentioning the Confederates are given the heroic spotlight, a choice that would not be made so casually today unless the hero was a bumbling moron like Joe Dirt.

Our hero, Johnnie, is far from inept, and after he gives chase in a different engine to retrieve “The General”, he discovers Annabelle has become an unwitting prisoner of the Union operatives. What follows is the greatest substance of the movie, locomotive chase sequences built around the Union soldiers trying to escape and delay Johnnie and then, with a small sequence of Annabelle’s rescue in between, the roles reversed with our hero’s escape and the Union troops in hot pursuit.

The sheer miracle of these sequences is Keaton and co-director Clyde Bruckman’s execution of a ‘bit’ being re-done in slightly different ways with the same hilarious results every single time. Not only are these sequences funny, most notably a great sight gag using railroad cars that disappear and return to slow down Johnnie, but Keaton is the one who not only sets them up but knocks them down by doing all these stunts himself.

As previously mentioned, Keaton’s vaudeville days prepared him for the rigors of physical stunts and he insisted on doing them himself. In the chase sequences, Keaton perfectly times picking up a stray railroad tie laid in the train’s path and then throwing it to fling it and another tie off the track. It’s an incredibly risky stunt, given one or both ties could bash you in the skull or you could miss and get whacked right off a moving train. While it is not Keaton’s most outrageous stunt—his falling wall stunt from Steamboat Bill, Jr. comes to mind—it highlights Keaton’s physical ability and savvy with even the most precise feats.

The physicality of the movie is evident not only in the stunts but also in some of the comedic action beats. One of my favorite elements of this movie is how it frames Keaton’s comedic stunts; such as jumping out of frame onto a bicycle or marching into frame to knock a Union soldier on the head with the butt of his rifle in order to save Annabelle. Keaton seems to thrive whenever his physicality and dexterity is put tot the test, and The General is one of the best examples we have of his master class of stunts and physical comedy.

As the chase elements of the movie wind down and Johnnie and Annabelle safely alert the Confederate army of the Union troops movements, the movie’s beauty, evident throughout, takes the forefront in a massive, for the time, set piece along a river gorge. In a scene shortly before this, Johnnie had set fire to the river’s bridge, hoping to cut off the pursuing train and the Union’s supplies. The Union general, undeterred by the fire because “the bridge is not burned enough to stop you,” sends the train over the bridge. In the biggest and most expensive stunt at the time, the Union train causes the collapse of the bridge and sends the train into the river gorge, where it is said to remain even today, ninety years after the movie’s filming.

The execution of the train’s wrecking and the subsequent battle that takes place on the river is stunningly shot and beautifully photographed. My favorite shot of the entire movie is of the two opposing armies advancing on the river while the plumes of smoke rise from the smoldering locomotive engine. In that moment, Keaton’s direction and the cinematography of frequent Keaton collaborators Dev Jennings and Bert Haines are at its most breathtaking. It looks as if it has been pulled straight from Francisco de Goya painting, but in sepia, and is an image lost to modern cinematic imaginations.

The execution of the train’s wrecking and the subsequent battle that takes place on the river is stunningly shot and beautifully photographed. My favorite shot of the entire movie is of the two opposing armies advancing on the river while the plumes of smoke rise from the smoldering locomotive engine. In that moment, Keaton’s direction and the cinematography of frequent Keaton collaborators Dev Jennings and Bert Haines are at its most breathtaking. It looks as if it has been pulled straight from Francisco de Goya painting, but in sepia, and is an image lost to modern cinematic imaginations.

With the Union army’s plan thwarted, our intrepid hero, Johnnie, must still woo his lady love, and finding a stray sword and still wearing his Confederate uniform he had stolen from the Union spies, marches into battle with the Confederates during the aforementioned battle scene. As he tries desperately to prove useful, my two favorite comedic moments take place. Johnnie’s sword breaks from its hilt and he keeps having to put his sword back on, only to lose it again. As he does this, a Union sniper begins taking out the artillery crew of a cannon and it looks like our poor, unwitting Johnnie will be his final mark. However, at the last second, Johnnie thrusts his sword outward to instruct the cannon to fire and his sword flies off-screen and the camera cuts to the sniper, dead with the sword in his back.

Having once again saved the day, Johnnie returns to the army camp a hero. After a stern admonishment from the Confederate general for wearing a uniform that is not his, the general enlists Johnnie in the army as a Lieutenant and Annabelle finally has her uniformed man. The movie ends with a classic gag moment. Johnnie once again sits on the piston arm of “The General”, but this time, he does not long for Annabelle, but she is in his arms and he embraces her in a kiss. However, soldiers begin to walk by the newly minted lieutenant and he must stop kissing his love in order to salute his fellow soldiers. Suddenly, the camera shows regiments of soldiers approaching. Johnnie, true to his contemplative and somber way, acts ingeniously and switches sides with Annabelle in order to keep kissing her and have his saluting arm free to satisfy the approaching regiments. It is a hilarious callback to previous shots and gags and is the perfect funny ending to a true classic.

Having once again saved the day, Johnnie returns to the army camp a hero. After a stern admonishment from the Confederate general for wearing a uniform that is not his, the general enlists Johnnie in the army as a Lieutenant and Annabelle finally has her uniformed man. The movie ends with a classic gag moment. Johnnie once again sits on the piston arm of “The General”, but this time, he does not long for Annabelle, but she is in his arms and he embraces her in a kiss. However, soldiers begin to walk by the newly minted lieutenant and he must stop kissing his love in order to salute his fellow soldiers. Suddenly, the camera shows regiments of soldiers approaching. Johnnie, true to his contemplative and somber way, acts ingeniously and switches sides with Annabelle in order to keep kissing her and have his saluting arm free to satisfy the approaching regiments. It is a hilarious callback to previous shots and gags and is the perfect funny ending to a true classic.

What Keaton defined for us in The General is a connection between the comedic performer and the everyman. If you or I were caught in situations as ridiculous as Johnnie, our reaction would not be one of emotive befuddlement. The hard-working ethic of Keaton’s character is evident in the impassivity of his reactions, and also, his sober plan to deal with what lies in front of him. It reflects the common thread of Proverbs which champions the “wisdom of the prudent”. His success is not hapless circumstance, but reasonable outcomes of careful planning in the face of danger.

“All who are prudent act with knowledge, but fools expose their folly.” Proverbs 13:16 (NIV)