For Western audiences, Akira Kurosawa is probably the most accessible of Japanese filmmakers. Kurosawa hybridized traditional Japanese and Western story elements to create something unique. His camera work is influenced by John Ford’s Westerns. He was one of the earliest to take Shakespeare’s plays and relocate them (In Throne of Blood he retells Macbeth in feudal Japan and in The Bad Sleep Well he sets Hamlet in modern day Japan). Nor was this limited to classic literature as he did the same to Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths and Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. All of this is to say that if you are someone interested in exploring world cinema, Kurosawa is a good place to start because he has already gotten the waters warm. His films are simultaneously familiar and strange.

For Western audiences, Akira Kurosawa is probably the most accessible of Japanese filmmakers. Kurosawa hybridized traditional Japanese and Western story elements to create something unique. His camera work is influenced by John Ford’s Westerns. He was one of the earliest to take Shakespeare’s plays and relocate them (In Throne of Blood he retells Macbeth in feudal Japan and in The Bad Sleep Well he sets Hamlet in modern day Japan). Nor was this limited to classic literature as he did the same to Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths and Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. All of this is to say that if you are someone interested in exploring world cinema, Kurosawa is a good place to start because he has already gotten the waters warm. His films are simultaneously familiar and strange.

Kurosawa was more than just a popularizer of western stories; he created his own stories that western audiences have retold in turn (The Magnificent Seven as Seven Samurai, Fistful of Dollars as Yojimbo, etc). In one instance, the influenced film is so famous that it is hard to even watch the Kurosawa original as its own film. Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress is best known as a primary inspiration for George Lucas’s Star Wars. Knowing this, there’s a strong temptation to watch the film as Lucas’s source material rather than as its own work (e.g. the two peasants are R2-D2 and C3P0, and like Princess Leia, Princess Yuki must escape enemy territory).

In this review, I’d like to focus on what I take to be the film’s message and ignore its commonalities with Star Wars. While the film does have several story elements in common with Star Wars, it does have its own perspective. While it’s not as “cool” a film as Star Wars, it is as substantive.

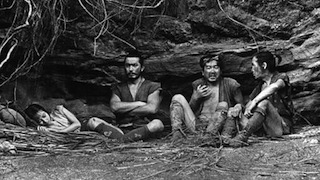

The Hidden Fortress focuses on two greedy, cowardly, peasants (played by Minoru Chiaki and Kamatari Fujiwara). The peasants go to war, and through a series of misfortunes, end up stripped of their armor and forced by the Yamana to bury the dead. The film opens with their failed escape. The Yamana recapture the peasants and force them to dig for missing gold. After a successful escape, they stumble upon gold hidden in tree branches. As the plot unfolds, viewers discover that a Yamana warlord has defeated the Akizuki clan and all that remains of the Akizuki royal family is the haughty, but kind-hearted, Princess Yuki (played by Misa Uehara), her General Rokurota Makabe (played by Toshiro Mifune), and a few elderly retainers. General Makabe has hidden what’s left of the royal treasure in branches. The Princess and the General need to get across the Yamana territory with the remaining 200 gold to the Hayakawa clan where the Akizuki has a peace treaty. Because they alone are unable to transport the gold logs, Makabe coerces, manipulates, and threatens the two peasants into helping them try to cross enemy lines.

While that may seem a little convoluted, very few of the details matter. The plot simply boils down to, can these four people safely get from point A to B while carrying gold. The basic plot seems more like a McGuffin-esque device to allow a series of events that deal with the themes of luck, equality, and character development.

While that may seem a little convoluted, very few of the details matter. The plot simply boils down to, can these four people safely get from point A to B while carrying gold. The basic plot seems more like a McGuffin-esque device to allow a series of events that deal with the themes of luck, equality, and character development.

Luck is the decisive factor in the film’s plot developments. With a few notable exceptions, luck, more than craft, gets them out of the binds in which they continually find themselves. The Yamana are looking for three men a woman and two horses, but they just recently had their horses taken from them and now they have a cart and another woman they picked up. The Yamana are trying to find people carrying wood, but they just happen to come upon people carrying wood to the fire festival. But, as is the nature of fortune, luck is not a perpetual blessing to the film’s protagonists. Just as often as it helps them, it is bad luck that continually forces them into these dire circumstances. In fact, luck is so transitory in the film, that often their luck changes from bad to good and back within seconds. Kurasowa continually plays with this such that you never can tell whether a favorable development is actually the resolution of one problem or the start of the next.

The film’s other major theme is equality of worth. This equality is of at least two varieties. The first kind of equality demonstrated is of class. Because Yuki and Makabe have to disguise themselves as peasants, they are forced to interact with peasants and come to know them. Princess Yuki discovers that the General’s sister has died as her double and she laments her death saying: “Kofuyu was 16…I am 16. What difference is there in our souls?” Yuki later discovers a former subject that has been sold into prostitution and fights to free her. General Makabe does not want her along because she would both slow them down and he has seen the wickedness of the two peasants he must rely on to help transport the gold across. Ultimately Yuki prevails and through the servant, viewers are provided a contrast. While the two peasants are viscous (at one point they draw straws to pick who will get to rape the princess), the servant girl is virtuous. There is no link between class and virtue. As Yuki has said, there is no qualitative difference between two souls.

Hidden Fortress also demonstrates Kurosawa’s sexual egalitarianism. In addition to the equality of virtue that the servant girl demonstrates, Yuki shows equality of capability. Early in the film, Makabe decides that Yuki will be unable to hide her higher breeding if she speaks. As such, he convinces her to pretend to be mute. Both Yuki’s voice and agency are systematically stripped from her by the general and the peasants they encounter. However, at the fire festival, when the crowd chants about the meaninglessness of life, Yuki’s voice is returned to her as she chants with the rest of the crowd. Later, that message and her voice will convince one of the Yamana generals to free them. The thing that Makabe thought would doom them is ultimately their salvation (again, as a matter of chance).

I want to avoid spoiling as much as possible, but I will say that you can track the development of these characters by how they respond to these elements. Early in the film, Makaba does not grieve his sister’s death because it was necessary for the nobility’s sake; contrast that with how he responds to the servant girl. The peasants will do anything for greed, but after realizing chance’s impact on life, greed seems less important (after all, the money they get can be quickly taken and their poverty can quickly turn to owning more than they could imagine). As the characters recognize luck and embrace equality, they are happier and better people. Equality is in part predicated on chance (after all, you could’ve been born a king or queen or too poor to own a device that enables you to read this). If there is no difference between our souls than it’s irrational to behave as though there were. And if the only reason to oppose you is my own advantage, why bother when chance could quickly reverse my advantage anyway?

Hidden Fortress is not a Christian film; however, like the rest of Kurosawa’s work, there is something strangely familiar in these foreign views. I take for granted that an audience that agrees to Gal 3:28 will agree with the equality Kurosawa presents. It is the luck aspect I find more interesting. Even if you’re a determinist that believes God has ordained every event, from our perspective this would appear no different than luck. Our fates are not ultimately our own and there is no telling how things will end. We may amass wealth only to hear that our soul is required of us this night (Luke 12:20). The message of James 4:13-17 is equivalent to the ground Kurosawa gets at with luck. While we cannot find comfort in the idea that even bad luck is okay because even if we die life had no meaning, and thus, we have lost only a dream, we can take comfort in the idea that even “bad luck” works for the good (Rom 8:28). By approaching these truths from a different angle, Kurosawa shows us why these things really are good, even if we ultimately disagree on their foundation. The freedom fortune provides is a freedom we have even if it is providentially grounded.

Hidden Fortress is not a Christian film; however, like the rest of Kurosawa’s work, there is something strangely familiar in these foreign views. I take for granted that an audience that agrees to Gal 3:28 will agree with the equality Kurosawa presents. It is the luck aspect I find more interesting. Even if you’re a determinist that believes God has ordained every event, from our perspective this would appear no different than luck. Our fates are not ultimately our own and there is no telling how things will end. We may amass wealth only to hear that our soul is required of us this night (Luke 12:20). The message of James 4:13-17 is equivalent to the ground Kurosawa gets at with luck. While we cannot find comfort in the idea that even bad luck is okay because even if we die life had no meaning, and thus, we have lost only a dream, we can take comfort in the idea that even “bad luck” works for the good (Rom 8:28). By approaching these truths from a different angle, Kurosawa shows us why these things really are good, even if we ultimately disagree on their foundation. The freedom fortune provides is a freedom we have even if it is providentially grounded.

If you’re interested in Kurosawa, this isn’t where I would start. Seven Samurai is a better film. Yojimbo is more fun and a better place to start if you like Westerns. But, if you’re trying to get a Star Wars geek to watch Kurosawa with you, this is definitely the place to start. Also, and it’s not something I’ve mentioned, but it’s a really enjoyable film filled with excitement and humor. It’s an adventure movie and feels like it. Like many Kurosawa films, the first hour is a little slow, but once you get started, you’ll enjoy it. It’s even streaming on Hulu at the time of this writing.