The word “Sicario” has its origins from the siqariqim, a radical splinter group of the Jewish Zealots, who operated during the time of Jesus and after to expel Roman rule from the province of Judea. One of the twelve apostles, Simon, was identified as a member of the Zealots; and even Judas Iscariot was, at one time in scholarly history, believed to be a part of the secretive and radical minority within the Zealots.

The word “Sicario” has its origins from the siqariqim, a radical splinter group of the Jewish Zealots, who operated during the time of Jesus and after to expel Roman rule from the province of Judea. One of the twelve apostles, Simon, was identified as a member of the Zealots; and even Judas Iscariot was, at one time in scholarly history, believed to be a part of the secretive and radical minority within the Zealots.

The Sicarii, which is the plural form of the Latin word for dagger or “dagger-man”, is widely believed to be the first organized group of assassins in modern times. Before the ninjas of feudal Japan and the Assassins of medieval Persia and Syria, Jewish resistance fighters banded together to form this “cloak and dagger” society to quietly murder important Roman citizens and Roman sympathizers and sow seeds of discord and incite rebellion and war.

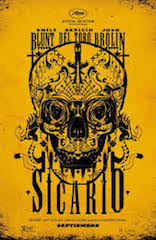

Denis Villeneuve, director of Sicario, opens the movie with this short definition of Sicario and blows the doors off our expectations when a SWAT truck literally blows the doors off a small, suburban home in Chandler, Arizona. FBI kidnap rescue specialist Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) and her partner, Reggie Wayne (Daniel Kaluuya), clear the house but after only a small bit of heat from those occupying the house, all seems lost. What they uncover behind a hole in the wall sets them on a chain of events that introduces them to Matt Graver (Josh Brolin), a government agent bent on bringing down the Mexican drug cartels, and Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), Graver’s tag-along with an unknown past and questionable ties to their operations.

The story progresses through a series of “ops” with Blunt being brought along for the ride but always kept in the dark, sometimes literally. Villeneuve never allows us to settle in as casual observers of Blunt’s fate, but what we know is directly tied to Macer’s own knowledge of the events. It’s a brilliant and effective device to build suspense throughout the film and during the dangerous operations, and it certainly delivers that suspense. But it is not the suspense of a horror movie, where you know a monster is right around the corner, but an, even more, off-kilter and disconcerting suspense.

And the action and suspense are never told in a way to give us quick cuts and easy answers. Villeneuve takes his time, allowing the camera slow, deliberate encroaching shots that do not take away from the thrills but stretch them out into a bewildering dissonance.

The most predominant feeling you get from the need-to-know nature of Macer’s involvement in the operation to take down the Mexican cartel is claustrophobic confusion. The camera stays unnervingly close during the action sequences and rarely gives us broader perspective. During one stand-out sequence in a drug smuggling tunnel, we see most of the operation in thermal cameras and night vision from a first-person perspective. What felt like a video game perspective, at first, plays out deliberately and very effectively with Villeneuve’s slow camera work, a tense, thumping score, and sound design that ratchets up the pressure. It’s as if we are experiencing the multitude of emotions and physiological reactions of Macer and the members of the “op”.

Blunt’s role in the film is far different from her role in last year’s Edge of Tomorrow. In that movie, she is a tough, no-nonsense solider and hero of the fight against the alien invaders. Here, while still resolved, she is unwitting and at her best when she is most vulnerable. She can hold her own as demonstrated by her extensive tactical success, but she is pushed around, knocked over, bruised, and wounded throughout the movie.

Her physical plight is also a good stand-in for her moral plight as she gets deeper and deeper into the war on the drug cartels. At every turn, she is looking to do things by procedure and bring down the cartel. However, her commitment almost gets her killed and makes her an easy target. What is most effective are the tactics employed by Brolin’s Graver. “Shake the tree and create chaos,” Graver says after her first taste of the action. “Nothing will make sense to you and you will doubt everything we do,” Alejandro warns her beforehand. She objects strongly and pushes back until it almost gets her killed more than once.

If Blunt’s Macer is the unwitting, righteous rag doll, then Del Toro’s Alejandro is the moral bludgeon and fulcrum of the movie. Shrouded in mystery, mildly aloof, and sagging with weariness, he starts off as an odd observer and a bit of a ghostly figure. Characters drop hints of why he is involved in the operation, yet it remains clouded, and when the major twist in the movie comes and his involvement is made clear, we’re left to wrestle with the moral gray of his motivations and the end results of his mission. Only then do we understand the second part of the opening definition of “Sicario” as the Mexican word for “hitman”.

Sicario should be seen for the great directing and filmmaking of Villeneuve, but also, for the bigger story it is telling about justice and achieving justice. Like the Sicarii of Jesus’ time, Brolin’s Graver and Del Toro’s Alejandro are out to prove that the only defense against an encroaching menace like the violent drug cartels is to create chaos and turn the enemy against itself through cloak and dagger tactics like assassination and violent retaliation. They would be more likely to call for the release of Jesus Barabbas than Jesus of Nazareth and agree with Christ’s axiom, “for all who draw the sword die by the sword,” but snub the castigative nature of his precept.

Blunt’s Macer may have more in common with Jesus than we realize. To seek justice through peaceful procedure is, in the movie’s opinion, likely to leave you battered, bruised, and broken. The grim conclusion of the movie leaves us wondering if there is a place in the world for anyone but wolves; if there is only evil fighting evil. I’d like to think that the lamb proved hanging on the tree is better than shaking the tree.

1 comment