Sci-Fi and horror are two unique dramas that allow filmmakers the space to create movies with unique visuals, obviously. But, it also gives filmmakers an alternate way to deal with complex inner-life and outer-life issues. From the meta realities of politics, science, and religion, to more thoughtful and specific realities of love, death, and relationships, these genres are uniquely equipped with monsters, demons, galaxies, and starships to tackle life’s most provocative complexities.

Sci-Fi and horror are two unique dramas that allow filmmakers the space to create movies with unique visuals, obviously. But, it also gives filmmakers an alternate way to deal with complex inner-life and outer-life issues. From the meta realities of politics, science, and religion, to more thoughtful and specific realities of love, death, and relationships, these genres are uniquely equipped with monsters, demons, galaxies, and starships to tackle life’s most provocative complexities.

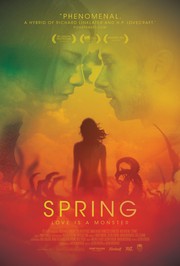

Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson, the team behind the poor man’s (or at least, “Indie man’s”) The Cabin In The Woods, 2012’s Resolution, use the quieter and less terrifying dimensions of the horror genre to lovingly unpack the emotional complications and fears of commitment, intimacy, and enduring through pain and loss. Set mostly along a quaint seaside town in Italy, Spring boasts fabulous sun-kissed vistas and a tranquility befitting of the tourist destination in which it takes places. Evan (Lou Taylor Pucci) is a young college dropout taking care of his ailing mother. When a post-funeral bar fight, predicated by his fragile state after his mother’s death, has him dodging the man he assaulted and the police, he boards a plane to Italy. After a brief tagalong with two UK denizens in Rome, he finds himself alone and without work in the unnamed seaside village where most of the film takes place.

Like any industrious young man would do when presented with no prospects for money or life, he finds work with a local farmer (Francesco Carnelutti) tending his orchard and finds love when he meets the stunning and mysterious Louise (Nadia Hilker). Initially meeting when he first came to the village, Evan had rebuffed Louise’s surprising invitation to come back home with her to bed. Evan eventually wins over her protestations at a relationship and they begin to date. While both harboring pasts they are reluctant to share with one another, it is Louise who enters the relationship with a darker and more frightening secret than Evan could have ever feared. I’ll save the suspense, as delving too much into the nature of Louise’s identity is a portion of the unease that permeates the movie.

Watermarked into the oceanic beauty of the Mediterranean and stamped into the gentle, pastoral beauty of the Italian countryside, this dread constantly keeps you from fully settling in to the charming love story unfolding between Evan and Louise. Inevitably, Moorhead and Benson’s cinematography will find comparisons, and rightly so, with Linklater’s After Sunset trilogy of movies. The same settings of the Italian coast and the sun-soaked imagery are tell-tale signs of the similarities, but also the thoughtful camera work that holds to capture emotion and inner-thought. The dialogue and direction can also find its influence in Linklater. Evan and Louise are witty, deep, yet realistically measured. Moorhead and Benson use long takes and few words to communicate the difficulties of commitment and intimacy, resisting the urge to translate complexities into inadequate and sappy dialogue, a symptom of many romantic dramas.

The horror elements of the movie only serve as a way to play on the unstated fears of the characters, not merely to get a jump scare or freak out the audience (although there is one good jump scare towards the end). Louise’s monstrous secret are symbolic, though not overtly, of who she is and the fear she carries of actually committing to someone she likes. Constantly trying to push Evan away, with good reason because of who she is, it takes the stubborn persistence of someone like Evan, who has little to lose from the relationship, to break down her barriers. It’s a poignant reminder to those who are paying attention that relationships are hard work. Falling in love and committing beyond the point of terror in a relationship, when the initial euphoria of being with someone new wears off, takes working through the ugliness of our baggage and emotional fragility. Evan embodies the spirit of every person who has seen past their partner’s looks and fallen in love with their heart. And when our inner monster shows, or in Louise’s case the real monster, it takes something more to continue in love.

The final third takes an unexpected turn and spends a little too much time explaining Louise’s being. However, there is adequate payoff at the end when the possibility of unrealized love buds into a tense and beautiful final scene. It’s fitting closure to Louise’s condition and Evan’s enduring love and faithfulness that reminds us of Christ’s love despite our own sin and ugliness.