I’ve never, in any meaningful way, consumed or been a part of the accouterments associated with the Evangelical Christian subculture. I didn’t grow up going to a youth group, I didn’t listen to Christian music, and I never read any books by Joshua Harris, DC Talk, nor have I ever cracked open a Left Behind book. While I can still identify the normal markers of an evangelical megachurch—I’m not blind—I am mostly unfamiliar with what it would be like to spend my formative years within the confines of youth group lock-ins, purity/promise rings, and Christian radio.

I’ve never, in any meaningful way, consumed or been a part of the accouterments associated with the Evangelical Christian subculture. I didn’t grow up going to a youth group, I didn’t listen to Christian music, and I never read any books by Joshua Harris, DC Talk, nor have I ever cracked open a Left Behind book. While I can still identify the normal markers of an evangelical megachurch—I’m not blind—I am mostly unfamiliar with what it would be like to spend my formative years within the confines of youth group lock-ins, purity/promise rings, and Christian radio.

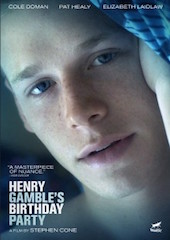

Stephen Cone’s 2015 multi-festival award-winning film, Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party, is firmly planted in this Evangelical Christian milieu. Content to toss aside the not-so-great trappings of the subculture–the main character unceremoniously dismisses Christian music as mostly “sucking”–Cone’s film swims in the spiritual and existential dilemmas of growing up in its subculture. The story takes place over one twenty-four-hour period at the upper-middle class suburban household of Henry Gamble, the teenage son of a Christian pastor celebrating his 17th birthday. As the guests begin to arrive, including Henry’s high school and church friends, the youth pastor and his wife, and other church friends, Cone weaves their stories together and uncovers sexual indiscretion, hidden pasts, and secret desires masked behind a facade of polite Christian maxims and unspoken rules of conduct.

Cone’s camera follows along with the narrative. It weaves in and out of the kids in the pool, the adults on the patio, and makes frequent trips inside the house to uncover the characters’ desires and story. As friend of Reel World Josh Larsen says in his review of the movie, there is a Robert Altman-like quality to Cone’s camera work and story. It functions as a fly-on-wall, buzzing in at opportune moments and zooming in closer to capture more intimate but clearly taboo details.

There is Henry’s mom, struggling with a painful secret. Henry’s friend Logan who clearly has eyes for Henry. Henry’s friend Gabe wants nothing more than to “score” with the church youth group head turner, Emily. When Bob, Henry’s dad, and the church’s pastor, invites Rose, the widow of Bob’s mentor and previous head pastor, and she brings her son Ricky, the dynamic instantly changes for many people. Ricky is an obviously unstable, insecure young man struggling to fit in, and Henry’s mom won’t even speak to Rose. As the day wanes and darkness falls, the hidden and secret are brought to light and we begin to understand more about the characters lives and its intersection with their shared faith.

The biggest issue this movie has is its portrayal of faith. The movie nails the more awkward, “Christianese” phrases and cringeworthy actions, like when the frat bro turned life coach youth pastor gives Henry the token Christian book every youth pastor gives a kid on their birthday. However, it goes no further in uncovering even a single character that carries a genuine faith in Christ. When confronted with anything beyond what would be considered the normal party line for evangelical Christianity, their rejoinders to biology being incongruent with faith in God or having a gay friend is sophomoric and meager. Likewise, when crises of faith are reached, no category exists for nuance. In multiple situations where characters are confronted with choices that challenge their faith, they either double-down on moralistic platitudes or wholeheartedly abandon obedience in favor of moralistic license. The movie trips on its inability to provide even narrow avenues for faith to address existential moral dilemmas.

Despite lacking the nuance to provide dialogue, it is incisive in portraying our culture’s obsession with sexual identity and how the church responds to both it and sexual indiscretion. What permeates many of the youth in the film are their varying comfort levels with their maturing sexuality and sexual urges. After masturbating in his bed, Henry prays before going to sleep. Gabe, Henry’s friend, screams for the Lord to forgive him while he commits a sexual act with another party attendee and is played for comedy. It’s revealed one character was allegedly aroused at the church’s summer camp in the showers, so he has become a pariah and the adults avoid him when he asks about going to camp again this summer. Another harbors guilt over her sexual relationship with a boyfriend and angrily lashes out when asked about it.

A lot of these situations do not happen until the final act of the movie, but Cone uses the house as cinematic geography to tell the story beforehand. The Gamble’s pool functions as the teenagers commons area where they play, dialogue, debate, joke, and make subtle advances. The adults are mostly confined to the patio and deck around the pool; focused more on politics, church-talk, and occasionally discussing the kids—the notable exception being the youth pastor who everyone knows is just a big kid anyway, right? The only times they truly co-mingle geographically is in one of my favorite scenes as the kids and adults share burgers, chips, and drinks together and sing “Happy Birthday” to Henry. It is captured in slowed down time, as the sun soaks over them, and choir-like music swells. It’s a genuinely human moment of communing together over a shared meal that strikes me as Cone’s vivid retelling of where significant “fellowship” actually happens.

The most significant narrative and cinematic metaphor come from one of the periphery characters; Larry and Bonnie’s daughter Grace. When she first arrives, she shyly says hi to everyone and mostly remains seated on the deck with her mother, Bonnie. She is often scorned by her mother and that she will not swim with the kids nor will she do anything that could be considered offensive to her very devout and stern mother. The treatment Grace receives is puzzling and unfair.

The most significant narrative and cinematic metaphor come from one of the periphery characters; Larry and Bonnie’s daughter Grace. When she first arrives, she shyly says hi to everyone and mostly remains seated on the deck with her mother, Bonnie. She is often scorned by her mother and that she will not swim with the kids nor will she do anything that could be considered offensive to her very devout and stern mother. The treatment Grace receives is puzzling and unfair.

But in another powerful moment of breaking this geography, Henry’s mom, Kat, decides to swim in the pool after confession has cleared her of a lot of guilt. She has her suit on and jumps into the water with the kids and others follow suit. Grace, against her mother’s desires, wanders down to the pool and doesn’t jump in, but gently dips in her toes into the pool and eventually sits down on the side of the pool with her legs dangling in. For the a fleeting moment, the self-righteous barriers have been torn down and grace mingles with these confused, curious, and genuine group of kids.

Overall, the movie struggles with providing a space for faith and the multi-faceted landscape of sexuality to dialogue in a way that doesn’t tip the filmmakers own personal hand. What I think Cone would say about sex, homosexuality, and faith is summed up rather inarticulately by Larry, Grace’s dad, when he semi-drunkenly quips, “We’re doing it all wrong people. You, you’re gay, that’s fine, if the Lord made you that way, f*** it.” However, Cone’s big idea is one I can get behind. Where Christian faith and questions of sexual identity and sin are concerned, we could all benefit from more grace.